The Day of the Test

Jim Eckles explains the challenges that Jack Hubbard, the meteorologist for the Trinity Test, had to overcome to predict a date and time for the test that would not be impacted by poor weather.

Narrator: Jack Hubbard, the meteorologist for the Trinity Test, had a very difficult job. When would the thunderstorms, high winds, dust devils, and other obstacles clear? Jim Eckles explains why predicting the weather was so vital.

Jim Eckles: The bomb was initially scheduled for July 4. They wanted to make it the ultimate firecracker, the Fourth of July firecracker. And then uncertainties and weather issues started interfering with that schedule and pushing it to the right further and further. The 16th was a day that the weather guy said looks like a good day, based on the typical summer thunderstorms rolling through at that time of year.

Everybody associated with the project that was familiar with New Mexico knew that the thunderstorms were going to be an issue at that time of year. Boy, they’re pretty unpredictable, and it really would have been tough back in those days. They didn’t have the satellite imagery and all of that. I mean, it’s all very unpredictable. And so, it would have been quite a nightmare. A lot of pressure on the weather guy.

There are a number of things to take into consideration if you’ve got storms. One is wind, high winds. You know, thunderstorms, it can be calm one minute and the next minute, the wind is blowing fifty miles an hour. And so, if you’ve got a storm like that blowing during the test, you are going to have radiation fallout going—God knows where—, because storms have got swirling winds and stuff, so that would have been very unpredictable.

It’s not a test just to see if it works—that’s a big part of it—,but you also want to try to get as much information as you can to see how it works, to collect as much data as you can to see how that implosion process is working and how sweet it’s going to be as far as the design and stuff. To be able to collect that data, you need pretty good weather. You need those cameras to be able to see things five-and-a-half miles away. You can’t do that in a thunderstorm.

Then there is the whole issue of lightning while the bomb is sitting on the tower, which is another reason driving the decision not to wait a day ‘til the next morning, but to go at 5:30 instead of 4:00. There is some pressure to get this test done, because you have got an armed bomb on top of a steel tower and lightning flashing around. It might set off the bomb, probably not, but it might damage the bomb. And then you are back to square one and you have got to start all over. So, a lot of pressure to go ahead and get the test done at 5:30.

During the Manhattan Project, Roger Rasmussen served in the Special Engineer Detachment. He describes waiting in the rain for the test. Meanwhile, a little ways ago, the unflappable General Leslie Groves was fast asleep.

Narrator: Roger Rasmussen served in the Special Engineer Detachment at Los Alamos during the Manhattan Project. He recalls waiting in the rain just a few miles from ground zero.

Roger Rasmussen: Where we stopped, we made tracks to get there. It turned out we stopped overlooking the flattest plain I had ever seen in my life. It was flat, flat, flat: nothing at all there. It turned out that we were overlooking directly towards the test site. We had the greatest view in sight.

Night came and we waited and it started to rain. What do you do in the rain? Well, you go sit on this wooden bench, in the back under the canvas cover, which is typical of World War II vehicles. And that got pretty hard after a while. It was that or under the truck. And so, we waited all night until about 5:00 in the morning. It had been a lightning thunderstorm. We were on the eastern edge of the storm, I think. Lightning and thunder to the west. The sky was beginning to turn light behind us, because it was east. The storm was still to the west. It was still almost pitch black, but it was getting light enough to see the ground in front of us.

We received our orders by radio from whoever was in charge of the eight of us. They said that they had decided they would still try to fire the test despite the weather.

Narrator: The director of the Manhattan Project was renowned for his self-confidence. Despite the tents flapping in the stormy weather, General Groves was able to catch a few hours of sleep.

General Leslie Groves: I went right to sleep at Alamogordo, when we had about three hours or four hours to wait for the bombing there. There, the tent ropes were slapping. Probably they hadn’t put up the tents tight, and there was a high wind. [James B.] Conant and [Vannevar] Bush were in the same tent with me—it was a brown little tent—and they said after, they said “How on earth could you sleep? We noticed you went right to sleep, and we stayed awake.” They said, “We don’t think we could have gotten to sleep anyway. But with those tents ropes rapping, how could you stay asleep?”

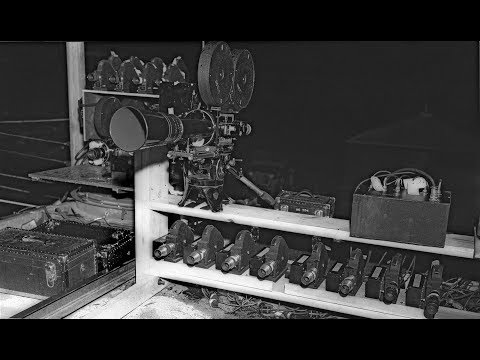

Manhattan Project photographer Berlyn Brixner recalls setting up 50 motion picture cameras to capture the Trinity Test.

Narrator: Manhattan Project photographer Berlyn Brixner describes photographing the Trinity Test, the world’s first nuclear explosion. Some 50 motion picture cameras were aimed at Ground Zero, where the explosion took place.

Berlyn Brixner: Kenneth Bainbridge put my boss in charge of the overall photography at the Trinity Site. My boss then put me in charge of the motion picture part of the photography. I finally got as many as nearly fifty cameras, motion picture cameras, in operation or ready to operate by the time of the explosion.

We had two sites north of the Zero and two sites west of the Zero, one at 800, one at 10,000 yards. They got rather a complete record of the explosion from the first ten-thousandth of a second.

I had lot of these Fastax cameras running at the near site until something like a minute or more after the explosion. So we got a complete record with those motion picture cameras of the whole explosion, something like 100,000 pictures were taken. The pictures that you look at, almost all of them are taken from the frames of those motion picture cameras.

Elsie McMillan remembers asking her husband Edwin what would happen at the Trinity Test.

Narration: J. Robert Oppenheimer decided to test the plutonium bomb or “Gadget” in the desert of the Alamogordo Bombing Range, about 240 miles from Los Alamos. Oppenheimer named the site “Trinity,” inspired by John Donne’s poetry, “Batter my heart, three-person’d God.” Elsie McMillan asked her husband Ed what to expect.

Elsie McMillan: Things were moving fast now. There soon would be a test near Alamogordo at White Sands, the very place we had visited with carefree abandon a few years ago. I asked Ed in all innocence what would happen. It seemed an easy question, with a simple answer. Knowing that it was an atomic bomb they were testing should have made me more aware of what would be involved.

It was difficult for Ed to tell me. He finally answered, “There will be about 50 of us present, key workers. We ourselves are not absolutely certain what will happen. In spite of calculations, we are going into the unknown.

“We know that there are three possibilities. One, that we will all be blown to bits, if it is more powerful than we expect. If this happens, you and the world will be immediately told. Two, it may be a complete dud. If this happens, you will also be told. Third, it may, as we hope, be a success, we pray without loss of any lives. In this case, there will be a broadcast to the world with a plausible explanation for the noise and the tremendous flash of light which will appear in the sky.”

With our alarms set for 2:30 a.m., Ed would leave at 3:15. We did not want to allow much time. We did not want to say goodbye.