Eckhart Hall

On December 2, 1946, the fourth anniversary of the Chicago Pile-1 going critical, scientists who participated in the experiment posed for a photograph on the steps of Eckhart Hall. Leona Marshall Libby was the only woman in the photo.

Narrator: One year after the end of World War II, some of the Met Lab’s leading scientists had a reunion. On the steps of Eckhart Hall, physicist Leona Marshall Libby stands out as the only woman. She was one of Enrico Fermi’s closest associates.

Leona Marshall Libby: He was a marvelously wise director of the scientific effort in the sense that he knew exactly where to be careful, and he could very frequently guess when it was unnecessary to make more accurate measurements. He had a very good sense of the degree of effort that would give the required result.

Narrator: Leona was also an outspoken defender of the work on an atomic weapon. In an interview, she recalled that Manhattan Project scientists feared that Hitler’s scientists were two years ahead in the race to create the atomic bomb.

Leona Marshall Libby: I think everyone was terrified that the Germans were ahead of us. That was a persistent and ever-present fear, fed, of course, by the fact that our leaders knew those people in Germany.

They led the civilized world of physics at the time the war set in, at every major university. So they were terrified. If they had gotten it before we did, I don’t know what would have happened to the world, but something different. Very frightening time.

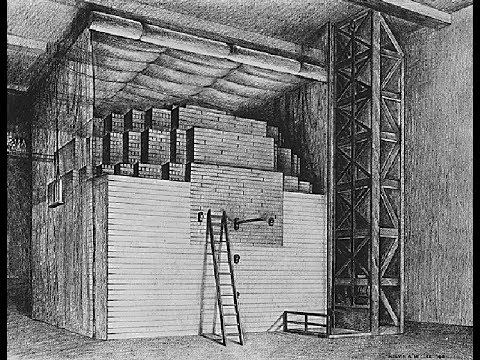

Physicist Ralph Lapp remembers how quickly the Manhattan Project moved from initiating a nuclear chain reaction to designing massive reactors.

Narrator: Veteran Ralph Lapp explains how quickly Manhattan Project scientists had to scale up in their efforts to design and build the first nuclear reactors.

Ralph Lapp: We worked at the University of Chicago. The mathematics building was where the Met Lab was centered. My laboratory was on the first floor right next to where the elevator came down. The elevator connected the first floor with the upper floors, which had Enrico Fermi, Arthur Compton, Robert Mulliken—all Nobel Prize winners.

But I used to keep the doors to my laboratory open at night. We worked seven days a week, eighteen hours a day. I was blowing glass and I had to have ventilation.

The elevator came down and Eugene Wigner—a Nobel Prize winner—looked at me and came in. He said, “I thought you would like to see this.” It was a black envelope stamped “Secret.” “Prototype Design up to 500,000 Thermal Kilowatt Reactor.”

Six weeks earlier at Stagg Field, the United States triggered a chain reaction, which generated half a watt of power. Half a watt! And they were proposing to go a billion times more in power.