Evicted from the Land

Annette Heriford and her family were forced off their farm when the Manhattan Project requisitioned the area. Heriford explains how the compensation offered could not begin to cover the investment her parents had put into their farm, and that they missed their lovely home after they left.

Narrator: The government offered displaced residents a meager twenty-five cents per acre for their land, barely enough to make a down payment to start over elsewhere. Annette Heriford remembers the substantial investments her family had made in their farm, and how sad they were to leave the beautiful bluffs behind.

Annette Heriford: We lived three and a half miles out. Had thirty acres there. They offered us $1,700. I have the papers on the pump, which was $895 to the Buckle Brothers. It cost $1,900 just to get the well in. We had overhead spray pipe, underground concrete pipe, plus the land, the purchase of the land.

Why, it was ridiculous! Ridiculous! Because no one could go any place. If they had said, “All right, if it is not worth anything, we will move you and we will give you thirty acres and we will put the same kind of well down. And you will have all your friends and your town right here.” If they had wanted to do that and they could have found a place comparable to ours, then great.

We would not have been as happy. We loved that Columbia River and the bluffs by it. That was a unique spot. It was beautiful, and it is still prettier than Richland, because of those bluffs.

In early 1943, the War Department requisitioned the Hanford Site for the Manhattan Project. General Leslie R. Groves, the director of the Manhattan Project, explains why the government allowed the farmers to harvest their crops before they were moved.

Narrator: In early 1943, the War Department approved the acquisition of more than 400,000 acres of land at the Hanford Site. For 1,500 people who lived on that land, this was a shock. Suddenly, their homes and farmlands were lost to the war effort. To avoid a public relations disaster, General Groves allowed the farmers to harvest their crops one last time.

General Leslie R. Groves: We permitted them to stay on and harvest their crops in the spring of 1943. It was done because it would have been very unwise to have people able to go out and say, “The government came in. They’re talking about saving food. They’re short of food. They’re asking us to save this and that. And then they come in and let all of these crops just rot!

So we permitted them to stay. The result of that was very disastrous financially for the government, because they had the best crops they’d had in years and years. In fact, of all time. Prices were extremely high. The juries all got very compassionate as to the price of the land, so we paid an awful lot more money for it than we would have if we had just taken it ruthlessly.

Narrator: After the harvest was complete, Army engineers chopped down the trees with ruthless efficiency, leaving only stumps where the fruitful orchards once stood.

Russell Jim of the Yakama Nation explains Hanford’s significance as his tribe’s wintering ground, before the U.S. Government requisitioned the area.

Narrator: For hundreds of years, Native American tribes fished, hunted, and camped along the Columbia River. Then the U.S. Government stepped in, and in February 1943, declared fifty miles of river and land, half the size of Rhode Island, “off limits” to the tribes.

Russell Jim, Rex Buck, and Veronica Taylor recall what those precious resources meant to the tribes at that time, and they share their concerns about the Hanford Site’s status today.

Russell Jim: The Hanford area was our wintering ground, the Palm Springs of the area. The winters were milder here, and so therefore we moved here and dispersed to all other parts of the country when the spring came.

We lived in harmony with the area, with the river, with all of the environment. All the natural foods and medicines were quite abundant here. As the snows receded, we followed back up clear into the Alpine areas, into the fall season. Then storing our food that we had gathered all spring and summer, we picked it up on the way back here to Hanford.

There is a concerted effort now by the Yakama Nation to influence the clean-up of the site. We know that it will never be returned to pristine status in the next 500 years, but at least there should be an effort to set the stage for clean-up.

Rex Buck of the Wanapum tribe explains what his tribe was told and how they felt when they were ordered to leave their land by Manhattan Project administrators.

Rex Buck: I can only tell you what I’ve been told by my elders, from my father who was here and my grandfather, who was still living here. They had a visit by Colonel [Frank] Matthias when the project was going to start, and he came to the camp up at Priest Rapids and talked to them.

They didn’t know what to think or what to feel, because they didn’t understand why they were going to have to leave an area. And they were only given so much time that they were going to have to get the few things that they could take and get. And they had several camps and several storage places that they had stored personal belongings, and also caches that they had different kind of foods and medicines that they had stored in certain areas. And they also had some equipment that they used for fishing, that’s unique to the Hanford area here.

What they understood is that this would be just for the war, that in order to protect the United States of America, that they were going to do something here that was going to help protect it. And that when the war was over, that they would be able to come back and that they would be able to reclaim and do some of the things that they had always done. So they felt good about that, but that never did happen that way as time went on.

Veronica Taylor of the Nez Perce tribe explains the short and long-term consequences for the Native Americans who were forced to leave their land when the government requisitioned the area for the Manhattan Project.

Veronica Taylor: A lot of the different tribes used to come here and participate in a lot of those different activities. The fisher people that lived along the Columbia River used to have fish, dried fish, and they would trade that for dried meat and game from other tribes that lived out in the plateau areas that had those kinds of food. It was kind of like, in our modern day, probably like a farmer’s market, where people came and traded goods and materials and foods with each other—the roots and berries and the medicines, the herbs and the teas. That’s some of the things that used to go on.

Nobody had ever told us, and said, “Well, this is what’s going to take place here. This is what’s going to happen to you and to your people.” Nobody said that that was going to be a problem—that it’s going to affect our water and our land and our animals.

They used to go hunting over here all the time for elk and deer and things. Now you talk to a lot of the Indian people to this day, they don’t want any animals from here. They won’t come here and dig roots here anymore, they don’t come here and get things that had happened in the past. It’s no longer available to them because people are scared to come over and get anything here anymore.

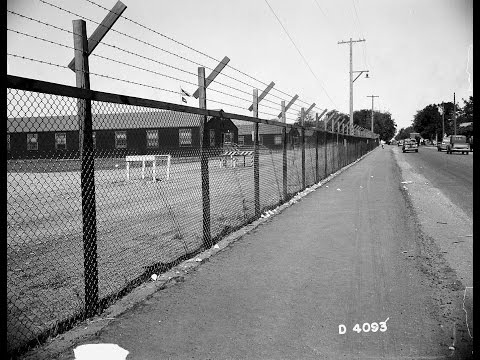

The Wanapum Indian tribe wanted to continue to fish and perform other traditional activities on the site. Colonel Franklin Matthias explained to the Wanapum Chief why passes were required for the Hanford reservation.

Narrator: In September 1943, Col. Franklin T. Matthias, appointed by General Leslie R. Groves to supervise construction at the Hanford site, reached an agreement with the Wanapum’s Chief, Johnny Buck.

Col. Franklin Matthias: I had a formal meeting with Buck, the chief, and I explained to him, I says, “If you don’t let us give you passes, and you are admitted formally through our gates, somebody in this big work force, anybody, could do some damage somewhere around, and they would accuse the Indians of doing it.” I said, “Relative to your fishing, all the time during construction, I’ll arrange to take your people who do the fishing up to the White Bluffs Island every morning in a truck. And you do your fishing, and take you back that night, or you could even maybe in some cases let you stay there overnight.” And so that settled that problem.