The Chicago Met Lab

University of Chicago physicist Peter Vandervoort explains how the name “Metallurgical Laboratory” was used to disguise the top-secret research being conducted at the University of Chicago during World War II.

Narrator: The Manhattan Project was the top-secret effort to create an atomic bomb in World War II. In 1942, the University of Chicago was selected for an important role: to design the world’s first nuclear reactors to produce plutonium, one of the key ingredients of an atomic bomb. As physicist Peter Vandervoort explains, to disguise its mission, the work at the University of Chicago was called the “Metallurgical Laboratory,” or “Met Lab” for short.

Peter Vandervoort: The University’s contribution to the Manhattan Project was organized under the so-called Metallurgical Laboratory. The name was chosen to obscure the fact that it was the venue for nuclear research.

The “Met Lab” was a cover. It would not have done to have called it the “nuclear research lab.” It would have been a giveaway. The name was chosen for the sake of security.

Physicist Samuel Allison served as director of the Met Lab from 1943 to 1944. He recalls the pressure-packed atmosphere at the University during the Manhattan Project.

Narrator: Physicist Samuel Allison describes the incredible excitement, tension, and sense of personal responsibility that Met Lab scientists and workers shared.

Samuel Allison: It was an atmosphere of incredible excitement and tension at the same time. University physicists are all individualists. It was extremely hard to get any order going.

There was practically no respect for authority. But still, things happened. I mean, young people would go out and do things which their superiors didn’t even know about, or certainly never authorized them to do. But they were the right things to do. And every academic person felt as if the whole project was his own personal responsibility.

Norman Hilberry was the assistant director of the Chicago Met Lab. He remembers how the laboratory rapidly expanded on campus in the spring and summer of 1942.

Narrator: Norman Hilberry became the assistant director of the Metallurgical Laboratory, or “Met Lab,” in 1943. He explains how the top-secret effort took over the entire row of stone classroom buildings along the north side of the old quadrangle.

Norman Hilberry: We started taking over buildings piecemeal. We took over the physics/math building first. The mathematicians, moving them out of their building was a rather serious thing. But on the other hand, they were good about it. They moved.

We just simply told them we had to have this space, and then the University backed us up in trying to get it freed up. We took over all of Ryerson [Laboratory] and all of Eckhart [Hall]. This meant the Physics Department had to be moved.

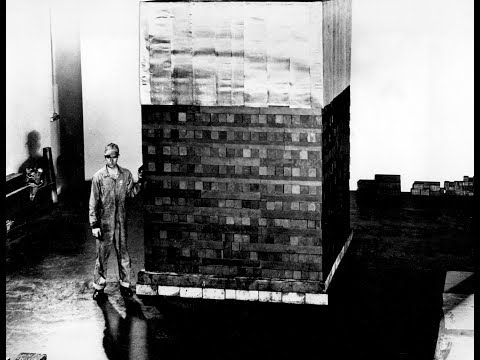

We had the cyclotron building, which was an old power house and dated way back, but it had been turned over to laboratory work. Then we took over the space under the West Stands, because it had a big squash racquets court, which would make a good place to do exponential experiments and things of this kind.

In March of ’42, we had forty-five employees at Chicago, total. This included the guards that we’d hired, and it included the telephone operators and everybody. But we had people that were going to be transferring in, and by July, we had something like 1,250.

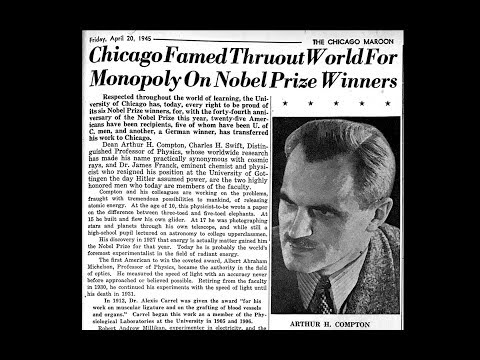

Abe Krash, the editor of the University of Chicago’s student newspaper, accidentally ran afoul of security regulations by mentioning Manhattan Project work on campus.

Narrator: Seventeen-year-old Abe Krash was the editor of the Chicago Maroon, the University of Chicago’s student newspaper. Military security was alarmed by the newspaper’s profile of physicist Arthur Holly Compton.

Abe Krash: Sometime early in April of 1945, I asked one of the reporters for the paper – I said, “Let’s do a profile, an article about Arthur Holly Compton.” The reporter wrote this article about Arthur Compton.

Two guys show up and they pull out from their pocket identification and sure enough, it was a major so-and-so and a captain so-and-so. We sat down in my little office. The major began by saying that the Maroon had committed a violation of the regulations governing newspapers and publications.

The circulation manager of the Maroon poked his head in the door, and said he wanted to tell me that all of our papers had been picked up. The newspaper was free. It was distributed throughout the campus.

The major, as I recall, cleared his throat, and said he had to tell me that the military had gone around the previous night and picked up every single paper throughout the campus, and also had gone to the printer and destroyed the plates.

Narrator: The military refused to tell Krash exactly how the Maroon had violated wartime security and sent him to see the dean.

Krash: He pointed to one sentence in the article, which said in substance that Compton had been engaged in research about breaking the atom. That’s the substance of what we said.

They were concerned that enemy agents, German or Japanese agents in Chicago, might read the Maroon, and from that might get a clue as to what was going on at the university. He then said, “They are engaged here in developing a great new weapon, which will revolutionize warfare.”

In reflecting on it later, I thought this was, frankly, kind of preposterous, if you stop to think about it. That anybody would find anything out by reading that article. First of all, there were military guards in front of these buildings, parading back and forth. It was obvious to anybody. Just walking, you would see that there was something going on.

But, more significantly than that, if you went into what was called the Reynolds Club, which was a big dining hall at the University, you would see there Enrico Fermi, Leo Szilard. Some of the most distinguished physicists in the world were there having lunch. Obviously, they were not there engaged in research on the Canterbury Tales!

The DuPont Company’s engineers had to work with the physicists at the University of Chicago to design the first full-scale nuclear reactors. DuPont’s Crawford Greenewalt and physicist Herbert Anderson discuss the challenges this posed.

Narrator: DuPont made Crawford Greenewalt the liaison between the physicists at the Chicago Metallurgical Laboratory and the engineers at DuPont headquarters in Wilmington, Delaware. The challenge was to translate the scientists’ theoretical ideas into blueprints for tangible devices. Greenewalt, who was a chemical engineer by trade, was justifiably nervous.

Crawford Greenewalt: I had my doubts. All these people I had met, they were eminent scientists. But none of them were engineers. And the DuPont Company was being asked to undertake this major undertaking. And all we had in assurances that there was any chance of this working or not, were the physicists.

Narrator: The Manhattan Project was a phenomenal collaboration of talented and dedicated people from a variety of disciplines and backgrounds.

Herbert Anderson: But I think it was handled beautifully by Greenewalt. His key engineers learned a lot. They worked hard, asked lots of questions and found out everything they needed to know.

Narrator: Physicists, engineers, and industrial experts joined forces to produce the many first of their kind facilities and devices need to produce plutonium.