After the War

Responses to the United States dropping the atomic bomb on Japan were mixed.

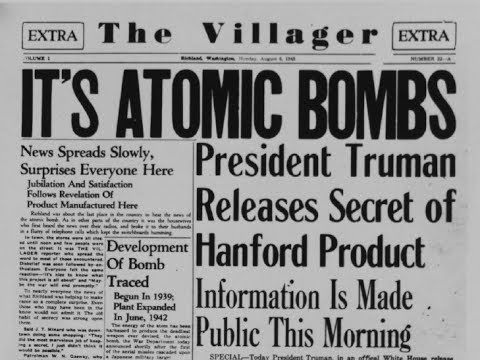

Narrator: Hanford’s African American employees had conflicting reactions when they discovered that they were working on the atomic bomb, as Jackie Peterson explains.

Jackie Peterson: I think a lot of people and the folks that I encountered that were interviewed about their experience or talked about their experience after they learned about the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were saddened and surprised that that’s what they

had been working on. But, at the same time, I think there was a feeling that that was the only way we would’ve won the war. The fact that they helped contribute to that was a source of pride for them for the most part.

I think there was a spirit of participating in something greater than themselves that, that a lot of African American folks in particular felt it was important that they contributed to. I think even something even that’s seemingly as small as working in construction on a military facility was a source of immense pride for people, because had they not built those facilities, none of those things would have happened.

Narrator: James Forde’s reaction was a mixture of pride and concern over the destructive capabilities of nuclear weapons. Both Willie Daniels and Luzell Johnson felt shock and dismay dismay when they discovered what they had been working on.

Willie Daniels: Well, if we all would have known what we were doing, some of us would not have been there. Some of us would have been frightened and left.

Luzell Johnson: All of that was surprising when we found out that, because, in the first place, the construction workers didn’t, they don’t get a chance to go back in those plants after they finished them. Every once in a while, we’d go back to repair something. We’d have to put on them shoes and coveralls and things. But I didn’t know what all of that was about. So, it was really surprising.

When I got back to Alabama, people there knew more about what was happening out in Hanford than I did, and I was working there. It just surprised us.

Someone said, “That’s what you were all making—we killed people.”

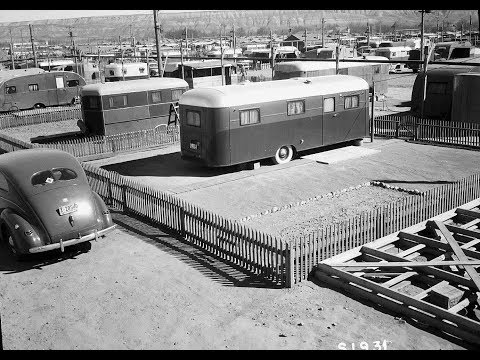

After the war, many African Americans settled in Oak Ridge, bringing their families and establishing the community of Scarboro. Kattie Strickland and her husband moved to Scarboro in the late 1940s.

Narrator: Because Oak Ridge did not allow children to live in the hutments, African American families often sought housing in surrounding communities. Kattie Strickland and her granddaughter Valeria Steele Roberson describe what their 1949 housing search was like.

Kattie Strickland: Momma kept them [the children] until we got them. My older daughter got, “Oh, no,” she really told me, “Oh Momma, I want to come where you are at now.” And we went and got them because they did not allow no children up at a certain time, but they just had opened up for children, you could bring your children. And we went and got them and brought them up here to Oak Ridge.

Valeria Steele Roberson: My mother wrote her a letter and said, “You have got to come and get us!” So they went down and got them and they were all reunited again. I’m sure that they were glad, when they could bring their girls up here.

They talked about living in the flat-tops. A flat-top has basically 2 bedrooms, one living area—you could use that for the living room—a bathroom, and a kitchen. It’s very small but it was theirs, and they could be there all together.

Six of them at the time. They were in one flat-top. Sleeping two people at one end and the other two at the other end. A lot of togetherness.

At the war’s end, many African American workers were terminated and expected to return to their hometowns. Expert Jackie Peterson elaborates on the post-war layoffs.

Narrator: Due to pressure from Washington State, many African Americans first returned to their hometowns before they returned to live in Hanford after the war. There was a deal between the governor of Washington and Colonel Franklin Matthias. Jackie Peterson describes it.

Jackie Peterson: Essentially, when Colonel Matthias approached the governor of Washington, the then governor of Washington, part of the provision of the governor giving the go-ahead for the Hanford project was that he forced Colonel Matthias to increase his budget for the entire project to ensure that there was enough funds available to send African Americans home, wherever they came from, once the Hanford project was complete. Because the governor did not want that many African American people hanging around in Washington State, which was pretty surprising to hear. So that’s part of the reason that there weren’t provisions made for African American families specifically, because they were just seen as temporary labor.

There were folks who attempted to go back home to where they were from and most of them, I think, found it very difficult to stick around. Not that there wasn’t racism in Hanford, not that there wasn’t discrimination in Hanford, but for some folks the degree to which they experienced racism in Washington State was significantly less than what they had experienced living in the deep South. So a lot of folks ended up coming back.

As the Cold War arms race with the Soviet Union began, the Atomic Energy Commission authorized the construction of new plutonium production reactors and support operations at Hanford. Many people, such as Luzell Johnson and Willie Daniels, were re-hired as the demand for personnel increased.

Narrator: When General Electric replaced DuPont as the Hanford government contractor in 1946, they began to expand the site and increased production. Luzell Johnson describes the racial situation he found when he returned to Hanford.

Luzell Johnson: But after I came back, every place that we went in they would refuse to serve me.

But I had good cooperation with the fellows who I was working for. We’d go in, and they’d say they couldn’t serve me. They’d say “Sorry, can’t serve him.” And all of us would get up and walk out.

I guess the word got around. By the time we got to the next place, they probably had called and told them what these fellas were doing and started serving us.

Narrator: After the war, Willie Daniels was hired to help with the experiments to test the effects of radioactive isotopes on animals.

Willie Daniels: We were feeding those isotopes and while they was making those experiments, you know, in the biology department, with those animals. They would use sheep, goats, and they had snakes, rabbits, chickens, cows, alligators. They’d experiment. In fact they’d put one up, see, in a cage and feed it those isotopes. And then, after so long, feed it some so long and then see what effect it had on them, you see. And, they’d go from there.

Well, we worked [at] 100 F [Reactor], that is where I retired from, 100 F.

Those who remained or returned to Hanford worked to establish a community in the Tri-Cities. They founded a branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and fought to obtain their civil rights and improve their lives. To learn more about the initiatives to record the history of African Americans at Hanford, visit the websites of the African American Community Cultural & Educational Society (AACCES) and Hanford History Project at Washington State University-Tri Cities.

Narrator: CJ Mitchell and Jackie Peterson reflect on the resilience of the African American community in the Tri-Cities and their persist fight for equal treatment.

CJ Mitchell: It took forever for my uncles. It took them many hours in city halls trying to get paved streets and sewers and stuff over there in East Pasco. Before I moved to Richland in ’55, they had what they called the East Pasco Improvement Association, which tried to clean up some of the old vacant lots that had a lot of trash and stuff on them, trying to clean them up to make the neighborhoods look a lot better. They had done all of that.

Jackie Peterson: People did, of course, stay in the Tri-Cities. They mostly just managed to open up their own businesses. Again, because there were so many restrictions on where people could go and what people could do that many African Americans ended up opening their own. People built their own churches, people opened their own dry-cleaning services, restaurants, shops within the Pasco community. So a lot of people were very successful with those businesses and ended up just staying because of that.

I think there’s this wonderful sense of resilience and ingenuity that in the face of losing jobs after the war, discrimination, people really rallied and did for themselves and did for the African American community in Pasco.

Narrator: African Americans’ experiences on the Manhattan Project were varied. But as CJ Mitchell saw it, the project offered him the chance to pursue a life outside of Texas.

CJ Mitchell: When you come out of segregation, you knew it wasn’t going to be any worse than that. You’re making a living. There’s work.

I’d be still in east Texas plowing a mule, really. If it wasn’t for the Manhattan Project, I’d still be there plowing a mule.