Chicago Met Lab’s Legacy

The Manhattan Project’s innovations profoundly changed how scientific research is conducted in the United States and led to the development of new fields.

Narrator: As MIT physicist David Kaiser explains, the Manhattan Project affected the entire structure of post-World War II scientific research in the United States.

David Kaiser: Our recent MIT President Susan Hockfield has said—and I think quite rightly—that our entire research enterprise in the United States really is built on a pattern, is modeled on the Manhattan Project. I think there’s a lot of truth to that.

The assumptions behind how basic research should be done, let alone applied projects or mission-oriented work, but even very basic research, which might not have an immediate payoff or immediate application—the system for supporting that kind of work really was fastened in a hurry under great duress during World War II in the United States. It had an enormously long-lived legacy. In fact, we really, in some sense, are still within it to this day. Many features that were put together in the 1940s still are how we organize and fund and disseminate the results from research today.

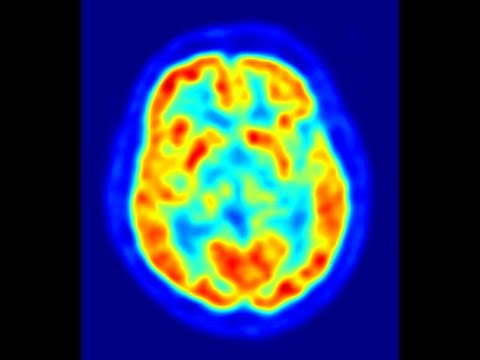

Narrator: The Manhattan Project’s work also led to discoveries in many new fields. Veteran Jim Schoke explains how the Project led to innovations such as positron emission tomography, or PET scans, imaging tests that allow your doctor to check for diseases such as cancer, heart problems, or brain disorders.

James Schoke: Nucleonics was—I do not know who invented it. But it was the term used for the new industry that derived from the atomic bomb, the Manhattan Project, that involved radiation, radioactive isotopes. And the necessary instruments and other devices that were required to apply them to industry, medicine, and research of all kinds.

I do not think the American public knows of all of the wonderful applications that have come from the nucleonics industry. They may not even tie it to the atom bomb, to the Manhattan Project. For example, if we had not had a Manhattan Project, I do not think we would have had PET scanners.

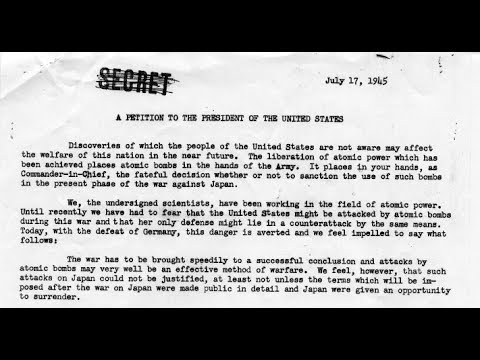

More than 150 Manhattan Project scientists signed the Szilard Petition, which attempted to avert the use of atomic bombs against Japan. Seventy of the signers worked at the Chicago Met Lab.

Narrator: In the summer of 1945, World War II raged on in the Pacific. Physicist Leo Szilard was concerned about the moral implications of using atomic weapons against Japan. Biographer William Lanouette describes the petition Szilard drafted to President Harry Truman. Truman never received that petition.

William Lanouette: Szilard remembered, “As an American citizen I have the right to petition the President.” And he drafted a petition to President Harry Truman for moral consideration for using this weapon before you use it on cities. In all, 155 Manhattan Project scientists signed it at Chicago and at Oak Ridge.

Narrator: Manhattan Project veterans Lilli Hornig and Jim Schoke recall signing petitions similar to the Szilard Petition. They describe their mixed feelings about dropping the bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Lilli Hornig: I remember the petition to—not to use the bomb as a weapon came around just after the [Trinity] test. And I thought about it and I thought that was a good idea. I think many of us had really worked on it with the thought that it might deter Hitler.

Once the European war was over with, there wasn’t certainly among the scientists the same gut feeling about using it. Of course, it made no difference, but we thought in our innocence if we petitioned hard enough they might do a demonstration test, something like they later did at Bikini and Enewetak, and invite the Japanese to witness it. But, of course, the military, I think, had made the decision well before that they were going to use it no matter what.

James Schoke: I have ambivalent feelings about it. I am very proud to have worked on the project and helped to get a weapon that ended the war. I signed a petition, which in effect suggested that the bomb not be dropped on a city in Japan. My feeling was that we should use it on a totally military target, not involving civilians.

Ralph Lapp and Henry Frisch describe the importance of the University of Chicago’s role in the Manhattan Project, from the development of nuclear reactors and weapons to subsequent efforts to establish civilian control over nuclear arms.

Narrator: Manhattan Project veteran Ralph Lapp and University of Chicago physicist Henry Frisch sum up Chicago’s role in “the nuclear story.”

Ralph Lapp: So I think that we could jump from such a flicker of flame—the reactor—to something a billion times more, and build it in less than two years, is really fantastic. It shows the enormous power of organized science and technology.

Henry Frisch: In some ways, the most important contribution was the role of the university in getting civilian control versus military control of nuclear things. The movement by the scientists to try to control access to nuclear material and weapons was an immensely important thing.

I think Chicago played an immensely important part in every aspect of the nuclear story. I think our history is such that we have both a responsibility and a tradition that we should continue. It shouldn’t be over. The story is not over yet.

The legacy that was left, the awe of nuclear physicists, the funding of high-energy physics, because it was the legacy of the Manhattan Project, as the generations go by, that all fades somewhat. It was a very special era of very special people and really remarkable achievements. I think Chicago played a very important role all the way through, from the start to the end.