Early Pioneers

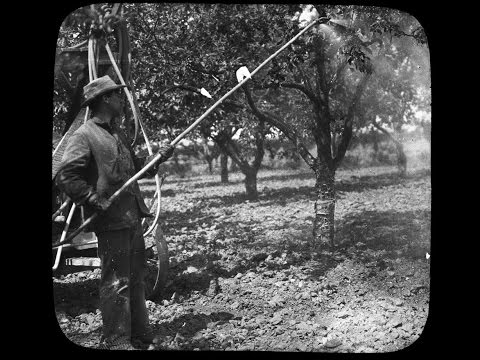

Mission Support Alliance archaeologist Tom Marceau describes how the Hanford Site by the Columbia River would have looked in the 1930s, with apple orchards and other abundant crops. Annette Heriford, who grew up at Hanford before the Manhattan Project took over the area, recalls her love of the lush apple orchards that her father grew and her fond memories of the community.

Tom Marceau: If we were looking at this area in 1930, we would have seen lots of agriculture. In fact, most of the agriculture on the Hanford Site took place on what they call the horn of the river, which is the area that the river bends and makes a large arc where it turns from going east-west to north-south. Most of the agriculture was there. This would be very, very lush and green. Alfalfa, apples, peaches, apricots. Lots and lots of soft fruits and apples being grown in this area.

Narrator: Annette Heriford was a young girl when her family moved to Hanford during the 1920s. She remembers the orchard her father owned and the community she loved.

Annette Heriford: From the time I can first remember, I loved the apple orchards. It was predominantly apple orchards, and then a lot of soft fruit also. I loved it from the time I was a child. I was the kind that loved my school and my town. I guess maybe I am a rare breed because a lot of people can just pick up and move and never miss their hometown. But I really loved the valley, and still would love to go back there and live.

We had Jonathans. They were my favorite apples, because they were juicy. I loved them. Then we had Winesaps. I think this is what Dad pulled out. He kept the ten acres of the Delicious, our best trees. We had thirty acres there. Part of that was in alfalfa that we kept. The rest was predominantly Delicious and then Winesap, Yellow Transparent or Winter Bananas, and then the Jonathan. The Jonathan was a good eating apple.

Robert Fletcher remembers growing up on his family’s farm in the 1920s and ‘30s.

Narrator: Robert Fletcher remembers some tough times on the family farm in the 1920s and ‘30s.

Robert Fletcher: These private irrigation companies were promoting this as a land of great opportunity for farming. It had a long growing season. It was light sandy soil. With the new irrigation to supply water to this dry land, crops would really thrive here and come on the market early.

Well, it could come on the market early, but it took a lot of work to do that. Some of these flyers said you could make a living on about five acres with strawberries and various other crops like that. They had a lot of hard work to get going.

I was born in this house, it was all they could afford at that time. But it was about half below the ground and so there were some windows above ground. Those bedrooms were really cold in the winter when you had a cold spell. My mother would warm up flat irons in the cook stove and wrap them in a towel or something, and we put them in our bed to get them warm. We had feather beds. Of course, we had chickens, so we had feathers.

We were very self-sufficient. That’s one thing that stands out in my mind, how self-sufficient my dad and mother and all the people living in Richland were at that time.

Department of Energy-Richland archaeologist Mona Wright explains the significance of the historic Hanford High School, the center of a thriving agricultural community before the war.

Mona Wright: We are standing in front of the Hanford High School, which was the center of the community in the early 1900s. The building itself was built in 1916.

The building was the center of the community. It served many purposes along with helping educate children and keep family community activities alive.

Behind the building, there was a small brick elementary school added in later years. There was a fire here in 1936. The building was reconstructed in 1937.

It is a wonderful testament, one of the few buildings that remain that demonstrate what people really believed their life would be like. They looked at educating their children, living on the land, and making a living, increasing their livelihoods, how they could, by selling produce and fruit from the orchards here around.

Robert Fletcher recalls the financial difficulties his family and others farmers faced during the Great Depression.

Narrator: In the early 1930s, the Great Depression brought especially hard times to farmers in the Richland Irrigation District. Many lost their farms, and the State of Washington threatened to foreclose on still more. Robert Fletcher remembers when his father traveled to Olympia to make a personal appeal to the Governor.

Robert Fletcher: The Richland Irrigation District had some tough times in the thirties. They couldn’t afford the bonds. Somehow or other the state had underwritten bonds to dig the canals. During the Depression years of ’29 up through the ‘30s, the farmers just didn’t have enough money to pay their bills. Some of them were foreclosed.

My father at that time became Manager of the Richland Irrigation District. He and John Dam and two or three others went to Olympia, because the bonds were being called and they would have foreclosed on Richland Irrigation District in about 1934 or 1935.

They got a chance to see Governor [Clarence D.] Martin. Somehow they got the loan on the Irrigation District reduced by over half. It was cut down to about one-third, because I guess there were no other options. Nobody else could operate the Richland Irrigation District. If they did foreclose on it, it would just return back to desert.

But there were some very difficult years there, that they had to do everything they could think of to survive.