Enormous Uncertainties

Historian James Hershberg describes the tension that permeated the Trinity Site before the test. Physicist Emilio Segre, who would go on to win the Nobel Prize in Physics, recalls his terror that the test would set the atmosphere on fire.

Narrator: The tension leading up to the Trinity Test affected everyone present; as historian James Hershberg describes.

James Hershberg: There’s a lot of nervous walking around, and there’s a lot of dark humor going around. Supposedly Enrico Fermi had been taking bets as to whether the first explosion would destroy the world, or just the state of New Mexico, or things like that. This sort of alluded back to the fact that in 1942, there had been a fear raised that, what if the first atomic bomb explosion ignites a chain reaction in the atmosphere that destroys all life on earth. The chances they came up with was with that the odds were just 3 in 10 million. They decided, “Those were acceptable odds. We can take that risk.”

Narrator: Manhattan Project physicist and future Nobel Prize winner Emilio Segre recalls how anxious he became before the Trinity Test, for good reason.

Emilio Segre: I asked and informed myself whether they were absolutely sure that the atmosphere wouldn’t catch fire. They assured me what they had done so, but you know, I mean, they can always make a slip. That thing was pretty fearful. So, I mean, I can’t say that I started to calm down!

The question of igniting the atmosphere had been taken quite seriously. People had calculated all the mass defects, all the packing fractions, and everything that one knew. And making all of the possible hypotheses, came out that there was no chance of igniting the atmosphere. But I’m enough of a physicist to know that you calculate everything, and then something happens that you never dreamed of.

Jumbo was a massive steel container built to contain the precious plutonium in the case of a fizzle. Manhattan Project veterans Ben Bederson and Harry Allen describe Jumbo’s purpose.

Narrator: Scientists were worried that the “Gadget” would not work. If it did fail to detonate, the plutonium at the core of the bomb was far too precious to lose. As Manhattan Project physicist Benjamin Bederson and procurement officer Harry Allen explain, that concern led to the creation of Jumbo.

Ben Bederson: My assignment was to study the ability of Jumbo to contain an abortive atomic bomb. If the atomic bomb did not actually work properly, the radioactive material would have spilled all over the landscape. It would have been a disaster of enormous proportions. So, the idea was to put the bomb inside this container. If it fizzled, then the container would hold it and keep it from spreading around and then destroying Los Alamos, essentially. If it worked, then it didn’t matter, because it would vaporize the container. So, that was what was called Jumbo.

Harry Allen: What they didn’t want to do was lose the very valuable and scarce fissionable material by just having it blown around in case there was no fission. You see, they wanted to save the fissionable material in this container so they could recover it and reuse it again. Of course, as it turned out, they got more and more confidence in what they were doing and decided it would do more harm than good to set it off in there, because they would lose a lot of measurements and so forth.

Jim Eckles explains how Jumbo made its journey from Ohio to New Mexico, and that tourists can see its remains at Trinity Site today.

Narrator: The Jumbo Containment Strategy did not quite complete its long journey. Its substantial remains can be seen to this day at the site. Jim Eckles recounts the story.

Jim Eckles: Babcock and Wilcox built this thing. The specs were for the interior diameter to be 10-feet and then the walls 15-inches thick, solid steel. They started with six-and-a-half-inches, thick pieces of steel. They had to roll them and bend them and then weld them together into a cylinder.

They got Jumbo onto the rail car to move it from Ohio to New Mexico. Well, they couldn’t just go—boomp—straight through, because bridges, tunnels, etc. couldn’t handle the size of this thing. So, they had to loop up through the upper Midwest and come back down and ended up at what they called Pope Siding, on a railroad west of Trinity Site. It’s down by the Rio Grande. They unloaded Jumbo on a huge trailer that had 64 wheels on it. They used a bunch of bulldozers to push and pull it up to ground zero.

By the time they got this all manufactured, hauled to the site and all that stuff, they decided not to use it, because it would interfere a lot with measurements—again, this idea of collecting data. If the bomb is all locked up in a bottle, you can’t see anything until the bottle gets vaporized or blown to pieces. So, there’s very little chance of collecting much information. Plus, they were more confident it was going to work.

Jumbo simply sat on the ground, 800 yards from ground zero during the test. The tower around Jumbo was just—boom—blown over, twisted, and mangled. Jumbo was undamaged, being a chunk of hot solid steel.

Then in 1946, the Army—who was up there, White Sands Missile Range—put eight 500-pound bombs in Jumbo, still standing on end, and managed to blow off both ends, and it fell over. And Los Alamos was really peeved. They had spent all this money to have this thing built, and then the Army had gone and blown off both ends, and they got no data.

Jumbo then laid in the arroyo, basically, for years. In the ‘50s, the nine inches of plating around the outer cylinder disappeared. We don’t know how or why. We’ve got a picture from the early-‘50s of it intact, but by 1960, it’s gone.

Then in 1979, the missile range, we moved to the parking lot, so the people could see it. People are always asking about it. “Where is Jumbo? Can I see Jumbo?” And so, we used a little Egyptian technology to move it over there and put it on display. People walk by it. The kids love playing in it. In there, you can see the jagged portion of one end of Jumbo where the bombs were placed, where they gouged out chunks of steel from the inside of Jumbo.

So, that’s the sad story of Jumbo.

Chemist George Kistiakowsky directed the Explosives Division at Los Alamos. He remembers his prediction that the Trinity Test would work, but that the explosive yield would be small.

Narrator: George Kistiakowsky and his team of chemists were confident that the explosive lenses they had created would work but they weren’t as sure that the “Gadget” would produce a great yield. The physicists’ position was the exact opposite and they eagerly bet against Kistiakowsky’s one-kiloton estimate of the yield.

George Kistiakowsky: But it was just a general feeling of superiority by the physicists over the chemists, who were in my division. Similarly, however, I had absolutely no confidence in the physicists’ calculations of the magnitude of the yield. And so, when I bet in that pool that was running there before the Alamogordo Test, I bet about one kiloton. I also bet Oppenheimer quite a bit of my money—about six or seven hundred dollars against ten-dollar bills—that the explosive part would work, and there would be some nuclear reaction. But I didn’t think it would be much of a reaction.

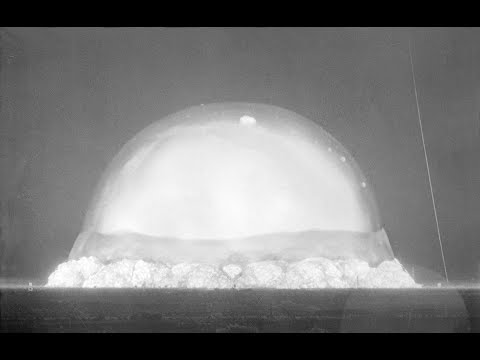

Narrator: Of course, Kistiakowsky lost his bet. The yield was enormous, about 20 kilotons. The explosive lenses and complex array of cables, wires, switches, and detonators all worked in unison to create an explosion of energy unlike anything the world had ever seen.

Manhattan Project artifact collector and expert Clay Perkins describes the Marley camera, which was used for some Manhattan Project explosives tests but was out of date by the Trinity Test.

Narrator: Manhattan Project artifact collector Clay Perkins discusses the high-speed Marley camera, which was used at Los Alamos but was out of date by the time the Trinity Test came around.

Clay Perkins: There were commercially available cameras that would run up to maybe 10,000 frames per second. That’s 10,000 individual pictures in one second. That’s very fast. They are called the Fastax.

They wanted to see many of the development steps of the bombs, and of course, then the actual explosion of the bomb that was tested at the Trinity Site in New Mexico, in more detail how things developed.

They found that there was a camera in England called the Marley camera—based on the name of the man who invented it and assembled it, used it for other things—and brought the Marley camera over here to take pictures of the Trinity Test.

These things worked with a spinning wheel of little slots in front of a mass of individual cameras, so to speak. One piece of film, but with multiple lenses. The geometry of that allowed pictures to be taken up to 100,000 frames in one second, which of course is getting pretty interesting. You got a bomb that probably most of it or all the reaction occurs in less than a second. Now you can cover the whole thing pretty well.

That camera was going to go down to the Trinity Site and be a very important piece. Well, other people had been working on high-speed cameras, too. By the time of the Trinity Test, the Marley was out of date. It was not used. It was used for other operations in the developmental process, but it wasn’t used for the famous first explosion.