Environmental Studies

The Manhattan Project hired the DuPont Company to design, build, and operate the Project’s plutonium production facilities in 1942. Crawford Greenewalt, a DuPont chemical engineer, adopted a radically new approach to environmental monitoring. Influenced by Ruth Patrick’s ecosystem approach, Greenewalt initiated monitoring of air and water quality, flora, and fauna to determine the impacts of Hanford’s operations on the environment.

Narrator: Crawford Greenewalt was a DuPont engineer with significant oversight responsibilities. He was a passionate nature-lover, determined to protect the environment. Biologist Ruth Patrick was an ecology pioneer who worked for the Academy of Natural Sciences. She convinced Greenewalt to use a radically new “ecosystem” approach. And so, during the Manhattan Project, DuPont was able to assess the impact of Hanford’s activities on Columbia River area ecology.

Ruth Patrick: You had to look at the whole ecosystem. You had to look at how the pollution was affecting the organisms they fed on, the places where they lived, the whole picture of what the organisms you wanted, fish, needed in order to live, and how the pollution was affecting any of these aspects of the natural life of the fish.

He made the decree that DuPont would build no plant and start to operate it, unless the Academy had first gone in and determined the condition of the river in which they were going to discharge. That was a revolutionary thing in those days!

Because of Crawford Greenewalt, DuPont was very conscientious about not discharging anything that would hurt the natural life in a stream. So, I would say to him, and he always bought it, “We’ll have to go upstream. We may have to get two or three places, if the kind of stream is quite different—chemically, physically—in different places upstream, in order to compare, when you damage the downstream, what it’s going to be like.” He always bought it.

Never once did Crawford Greenewalt say to me, “That costs too much money.” He would question me as to whether it was necessary, what was I going to learn by doing this extra work. But he never said, “We can’t do it because it costs too much money.”

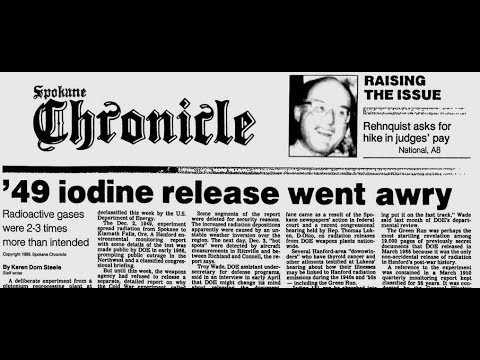

Michele Gerber, historian of the Hanford site, describes the controversial Green Run test of early December 1949. In 1986, Karen Dorn Steele, the Spokane journalist who broke the Hanford story, was able to link people’s mysterious illnesses to the Green Run and to radiation releases to the air and the waters of the Columbia over more than forty years.

Narrator: On August 29, 1949, the Soviet Union tested its first atomic bomb. Shortly afterwards, Hanford’s air filters detected the radioactive iodine-131 emissions produced by the Soviet test. The Department of Defense wanted to run a test on Hanford’s air filters to determine how well the filters captured the iodine-131 gas and the gas’ dispersion pattern. From December 2 to 3, 1949, Hanford conducted a test, known as “the Green Run.” Historian Michele Gerber talks about the Green Run’s fallout in the area.

Michele Gerber: The problem was that the late fall in the Columbia Basin is always full of fog and inversions. It’s very characteristic here, and that didn’t mesh well with the plans of the Department of Defense to run a test here at that time. By the time they got organized, it was November, and the fog is rolling in. And the Department of Defense officials were here for two or three weeks waiting for a clear day. They didn’t get a clear day. And they finally got what they thought was going to be an okay day to run a test, where they would release quite a bit of iodine gas and then monitor the filters.

They had filters set up all the way to Spokane, all over the area, and they were going to gain their data. They did release the gas, and an inversion moved in and it actually rained. So, it wasn’t just wet fog; it was actually raindrops. And the gas came down close in and heavy. And so, that was the Green Run, where exposures were very heavy around Walla Walla, Franklin County, just east of the Hanford Site and just north.

The greatest exposures were almost an ellipse, and it curved just a little bit north and east of the site and went up to the town of Connell, thereabouts, almost to the town of Ritzville. And then, it sort of bulged out to the east, covering Franklin County and Walla Walla County.

In 1984, Karen Dorn Steele, a reporter for the Spokesman-Review, began to report on cancers in farm families and heart attacks in young men working the fields in the farmlands across the Columbia River from Hanford. In 1986, the Department of Energy, responding to growing public concern over the safety of Hanford as a nuclear neighbor, declassified thousands of pages of early Hanford environmental monitoring records. These documents disclosed the secret widespread release of radioactive iodine-131 and other harmful radionuclides and chemicals that occurred beginning with the start-up of the facility in late 1944 and continuing over forty years thereafter. The Green Run Experiment of December 1949 was disclosed by these records. Karen Dorn Steele began to cover the revelations contained in the declassified documents as she and several Spokane journalists who were members of HEAL, the Hanford Education Action League, combed through them. Steele’s reports on the Green Run and the chronic, secret releases of radiation to the air and to the waters of the Columbia River stunned the public. Over 750,000 curies of I-131 and a range of other biologically significant radionuclides had been released throughout eastern Washington, northern Oregon, into Idaho, Western Montana, and into British Columbia. Steele’s reports also galvanized support for the Federal Facilities Compliance Act of 1992 that required facilities’ compliance with all Federal, State and local hazardous and solid waste laws.

Narrator: The Atomic Energy Commission did not warn the public about possible exposure to iodine-131 or other radioactive gases, or about radionuclides in the Columbia River. Afterwards, many people reported mysterious health complications. But because the Department of Energy did not reveal the facts about Hanford’s radiation releases until 1986, it was decades after the war before many people were accurately diagnosed. Interviews with Hanford area residents conducted by Spokesman Review reporter Karen Dorn Steele in the mid-‘80s helped to uncover patterns of cancer and other diseases common to the region.

Karen Dorn Steele: We filed our FOIA request and so did the Environmental Policy Institute of Washington, D.C. and HEAL, the Hanford Education Action League. When we went into court, the government argued, “Well, we can’t release these, because it might give away the secret of the bomb.”

We said, “We’re not asking for the details of how you make a bomb. We’re asking for the environmental monitoring reports, which showed whether or not there were offsite releases or accidents onsite.”

There was mounting public pressure to release these documents. And so, six months later, in February of 1986, they actually released them.

I just thought logically it would be good to start at the beginning with the ‘40s. We didn’t know at the time what even the emission figures meant.

All of a sudden, Tim Connor from the Hanford Education Action League—we were sitting around a big table. He said, “Take a look at this.” It was the December 19, 1949 quarterly monitoring report.

When we looked inside, there was this graphic of this huge plume of radioactive iodine that had spread throughout Richland, where the scientists lived. Usually the dispersion stacks, 200-foot-tall stacks, would disperse it away from the nuclear reservation. But the radiation fell on the reservation. It had plastered Walla Walla, it had spread all the way to Spokane. It was stunning.

June Casey had a pretty scary story. She had just transferred to Whitman College, and she was a sophomore. And she was there during the Green Run, and that was her first semester at Whitman. When she went home, she was from Oregon—Umatilla, I believe—when she went home for Christmas, she was just exhausted. She could hardly get out of bed.

And then, her hair started falling out in huge clumps. She had long, curly brown hair. It never grew back. She didn’t know what it could be. It was a mystery, a medical mystery. Her parents, of course, were just really seriously concerned for her.

She didn’t know about the Green Run until she read a story in 1988. It was two years after the original reporting. But she lived in Oakland, California, so she saw a follow-up story on the Green Run. And, finally, she thought, “Maybe this is what happened to me.” You know, it was dramatic.

The discipline of health physics, which studies the effects of radiation on human health and the environment, started at Hanford. Gary Petersen, Hanford’s former news manager, talks about Hanford’s testing of animals to better understand the impacts of radiation on human health.

Narrator: Health physics research scientists at Hanford Laboratories studied the effects of radiation on animals, hoping it would help them to better understand how radiation affected human beings. Strontium-90, a byproduct of nuclear fission reactions, is chemically similar to calcium. Gary Petersen recounts a time when Hanford tested to see if this potential cancer cause could penetrate the thick skin of alligators to get into their bones.

Gary Petersen: Hanford Laboratories was started in the early days of Hanford. This is one of the fascinating aspects of Hanford that is probably the most unsung of all of our stories. When they first put in the reactors, and there were nine reactors all on the Columbia River, and the last one on the downstream side was called F Reactor. They wanted to know the effects of the reactors on the aquatic life in the river. They started with aquatic biology, and health physics actually started here as well.

An example of the kinds of work that aquatic biology did. In 1963, two DVMs, Doctor of Veterinary Medicine, went to the head of biology, who was a guy named Bill Bair at the time, and said, “We need to study the effects of radiation uptake in thick-skinned animals.” Because certain radioisotopes are bone-seekers or thick-skinned or those kinds of things. They talked Bill Bair into allowing them to buy six alligators.

This is my alligator story. The alligators were about two-foot long. They were young, and they were going to study strontium-90 uptake in these thick-skinned animals. They were put at 100 F area, in a pen in the river, because the water flow came by, you know, the last downstream. They started studying these animals to see if any of the radionuclides would go into the skin and the bone.

Well, a storm came up, and the storm blew down the pen that the six alligators were in. They all escaped into the Columbia River. This is still during the Cold War. This was classified or under wraps, however you want to say it.

The workers out there, they found five of the alligators. One was still missing. Time went on—this was 1963, before I got here—time went on, and there was a fisherman downstream at a place where everybody went. He caught this sixth alligator, and people wouldn’t believe that he caught an alligator in the Columbia River. But the man took the alligator to a taxidermist in Pasco and had it stuffed. He wanted to preserve it.

Well, a technician from 100 F [F Reactor] was walking by the taxidermist shop, saw this alligator in the window, and knew what it was. He ran in, grabbed the alligator, and took off.

I got here in ’65. In late 1965, my boss, a man named George Dalen, called me into his office one day. He says, “Gary, it’s time we gave Aaron his alligator back.”

“What are you talking about?” I said.

George reached down, and here’s this stuffed alligator, about like so. He says, “Aaron caught this over at a place called Ringgold, downstream of F Reactor, and we went and took it from him.”

I will tell you that the story has been in the Tri-City Herald, so it’s a provable story.

Narrator: Hanford scientists eventually determined that strontium-90 did get into the thick skin of the alligators. The Hanford Laboratories continued health and environmental research, and today is known as the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. Studies of sheep showed that varying levels of radioactive iodine I-131 caused deformities in lambs, and eventually death in ewes.