The Great Migration

The first wave of the Great Migration brought millions of African Americans to northern urban centers seeking jobs, higher wages, and an escape from Jim Crow laws in the South. Scholar and exhibit designer Jackie Peterson describes the causes of this wide-scale exodus. Historian Valeria Steele Roberson highlights African Americans’ patriotism and the community her grandparents left behind.

Narrator: From World War I through the Great Depression, millions of African Americans began moving out of the South in what is known as the Great Migration. As the United States entered World War II, a second wave of the Great Migration began as African American families left the often violent racism of the South for opportunities in the North and West. Jackie Peterson, who curated the exhibit “Atomic Frontier: Black Life in Hanford,” describes the Great Migration from the South during World War II.

Jackie Peterson: World War II was one of the largest waves of the Great Migration, sparked a lot of movement across the country. A lot of urban centers had a lot of, again, a lot of these job vacuums that were created by mostly white men going off to fight in combat. So a lot of African American men in particular, but also women and families just packed up and decided to take their chances, particularly in urban centers in the Northeast and the Midwest.

I think for a lot of African American folks living in the South, they were living through Jim Crow, which was very serious discrimination, segregation, repression, oppression. It was very difficult for people to get jobs, particularly following the Great Depression.

There was barely work for European-Americans, let alone African Americans, and so people were making five, ten cents an hour if they were lucky to find a job working across the South.

I think that things were so bad for African American folks that there were very few opportunities for them where they were living. So I think there was this feeling that there had to be something better, and so when the United States decided to enter World War II, that opened up a lot of doors for people.

Narrator: Historian Valeria Steele Roberson describes her own family’s experience living in the Deep South.

Valeria Steele Roberson: During the Great Depression down in Alabama, they were really poor. The good thing about my family is that they were always able to produce enough food for everybody to eat. They essentially sort of lived together—my great-grandmother, my grandmother, aunts, uncles, cousins. They would take everybody in, and work the farm, and try to get jobs outside of the home to make ends meet.

Right before the ‘40s, when all that was going on, they were longing for an opportunity to make some money, to better themselves here in life. With the war starting and blacks going off to fight for the country—because they have always been patriotic, always wanted to be a part of it, to do their part—there was a lot of pressure put on the government to allow blacks to work on the Manhattan Project so that they wouldn’t have to march on Washington, which was being threatened.

Because a lot of people were starting to realize that, if we are giving our lives for this country, we should be treated as American citizens should be. Everybody should be treated equally. We want a bigger piece of this pie so that our families can become better and prosper as well. We want to be treated as equal citizens.

During World War II, the United States launched a massive secret program to develop an atomic weapon, known as the Manhattan Project. After an experimental reactor in Chicago (Chicago Pile-1) proved successful in December 1942, Manhattan Project officials hired the DuPont Corporation to construct and operate full-scale plutonium production facilities at Hanford, Washington. In 1943, DuPont recruiters like Phil Gardner began aggressively recruiting underpaid laborers from the South to build the massive complexes.

Narrator: The Manhattan Project was the massive U.S. wartime program to develop an atomic weapon. In 1942, General Leslie R. Groves, who led the effort, hired the DuPont Corporation to build plutonium production plants. To find laborers, DuPont looked to the South, states like Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia, offering good wages and a ticket to the project site in Hanford, Washington. Jackie Peterson describes the recruitment process.

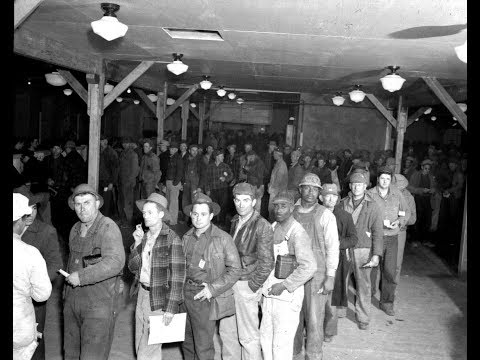

Jackie Peterson: Initially, the Manhattan Project recruitment strategy was, I feel, slightly self-confident. People thought, “Well, we’re just going to put it out there. If you build it, they will come.” And, so they got an initial wave of folks primarily through in-person recruitment. There were teams of folks who would literally, day-by-day, show up in different places in the country.

People would turn up at their office; they’d be given a little ticket with their name and number. And again, if they were fortunate to have the funds, the individuals would be given some money to pay for their train or bus fare. Then they would show up in Hanford and turn in the ticket they were given at the recruitment office.

Once people started to get wind of that, they kind of figured out where to go, a lot of people just bypassed that sort of formal showing up at the office process and just ended up showing up in Hanford. They would drive, they would take buses, and they would say, “Hey, I heard this radio ad,” or “I saw this in the newspaper. I hear there are jobs here. Can I work?”

I think at the time, people were so drawn by the financial opportunity, that it didn’t really matter that they didn’t know what they were going to be working on.

Narrator: Phil Gardner travelled over 100,000 miles recruiting employees of all backgrounds for Hanford. He describes the Manhattan Project’s desperate need for workers.

Phil Gardner: We were paying $1/hour. There was a big shortage. We were hiring a lot of these people—we were taking their word for it that they were mechanics.

Well, I recall one day in Kansas City, Colonel Matthias, who was a commanding officer on the job, and Gil Church, who was the project manager, were out visiting me and calling on the War Manpower Commission to impress on them the importance of this job.

Well, we got back to the hotel, the Colonel asked me if it were true that our recruiters would hire a man as a carpenter if he could identify a hammer. We said, “Well no. We’re not quite that tough. If he could convince us that his father would have known what the tool was, well we’d probably just take him.”

As the country recovered from the Great Depression, steady work and high wages attracted many workers to the Manhattan Project’s “Secret Cities.” As word spread about opportunities at Hanford and Oak Ridge, Tennessee, individuals like CJ Mitchell followed relatives to get a job.

Narrator: Oftentimes, after a person left to work for the Manhattan Project, their families and friends followed close behind. Valeria Steele Roberson remembers her grandfather moved to the Manhattan Project site at Oak Ridge, Tennessee.

Valeria Steele Roberson: First my grandfather came, Willie Strickland. That’s how it is, one person comes, and then more family people come. They had to leave Alabama because they were very poor, as I said before, and also they weren’t making much money. So this was an opportunity for them to come and to better themselves, make a better life for their whole family.

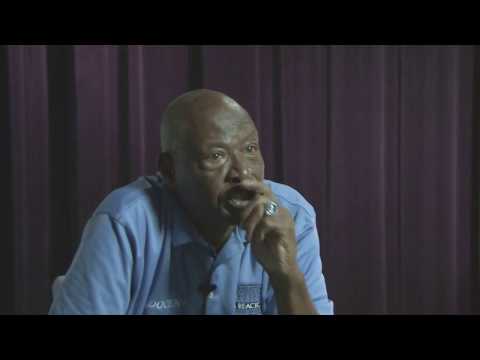

Narrator: CJ Mitchell arrived at Hanford after World War II, lured by his relatives’ reports of wages three times greater than what they could earn back home.

CJ Mitchell: My uncles and other relatives coming through, they had worked out here [Hanford] and they had come back home. They could earn much more money – about three times the money – here than they could earn back there. And so, the word got around. You know, it got around pretty fast. People were going not only to out here, but they were going to California, Houston, Dallas. They were beginning to migrate different places because of the work and the war, and the opportunities there.

Narrator: Luzell Johnson was working in Alabama when he was recruited by DuPont.

Luzell Johnson: I was working in Mobile, at a creosote plant. They had recruiting. I heard about it and so we could get tires and gas to come out here. And so I went to the office and they got me on that job.

Narrator: Willie Daniels heard about the high wages at Hanford while working in Vancouver, Washington at a naval base.

Willie Daniels: They are hiring over there and say, “It’s a dollar an hour over there and that’s more than I’m getting here. And I would like to get released so I can go back over there.”

Some African American scientists and lab assistants joined the Manhattan Project through referrals. James Forde and George Warren Reed were employed at laboratories in New York City.

Narrator: About 5,000 New Yorkers worked on the Manhattan Project in Manhattan during the war. James Forde was hired by Union Carbide to work as a lab assistant at the Nash Garage Building in New York City.

James Forde: I was laid off, but I was eligible for unemployment insurance. In those days, and I do not know what it is like now, you go to the unemployment insurance office and they could send you out on jobs that they thought you were qualified for. They sent me to the Union Carbon and Carbide Company. They had an office in Midtown Manhattan. I went there and they hired me. They sent me to what turned out to be what you are now calling the Nash Garage on 132nd Street and Broadway. That was the Manhattan Project.

Narrator: After graduating from Howard University, George Warren Reed began working as a scientist at Columbia University’s Substitute Alloy Materials Laboratory.

George Warren Reed: The chairman of the chemistry department–a white guy–was working on the SAM project, which–of course we didn’t know it at the time–but was the atomic bomb project in New York, at Columbia.

There was another person, a man named Ed Russell–was a black guy–who had come up to Chicago and he was working at the Met Lab in Chicago. I got in touch with them, because I wanted to do chemistry if I could. But I was classified 1-A [eligible for military service], so I didn’t know what was going to happen. I was invited to come to New York and then to come to Chicago. I went to New York and I was interviewed by a man named Simon Freed, who was a professor from the University of Chicago.

I went on to Chicago. And when I got there, I was told, well, things are slowing down there and they weren’t hiring. Well, I got a wire from New York saying, “Well, we can use you.”

So, I’m back in New York and I worked at Columbia [University] first and then we moved up on Broadway–to a big old warehouse. And I worked there for–I don’t know, a year and a half or something like that.

Few restaurants, hotels, or other lodging welcomed African Americans. This left them vulnerable to racist violence.

Narrator: For much of U.S. history, travelling across the segregated South as an African American was a dangerous endeavor, as explained by scholar Jackie Peterson. CJ Mitchell recounts his own long journey which went from Texas to St. Louis and eventually to Pasco.

Jackie Peterson: For me it’s kind of a miracle that people ended up at Hanford of all places, because travel for African American folks in the ‘30s and ‘40s was a fairly dangerous effort, particularly because lots of folks travelled by car at that time, usually because it was the most affordable way to do anything. And so, because of racism, because of racial oppression, and because so much of the country was unknown to a lot of people, it’s amazing to me that people just picked up on the hope that what was the other side was going to be much better than what they had already known. That people just packed up their cars or got on a bus and hoped that they would make it in one piece.

CJ Mitchell: I’m on the bus, and I’m on the train. I get back on the train, and we’re heading on out to Chicago. That’s the first time, with my uncles.

When you leave Texas in those days, you come to Saint Louis.

When you got to St. Louis, you don’t have to ride in the segregated cars anymore, once you go to St. Louis.

Chicago, Minneapolis, and St. Paul. Then you come down through Billings, and down through that to Pasco. That’s the way you came.