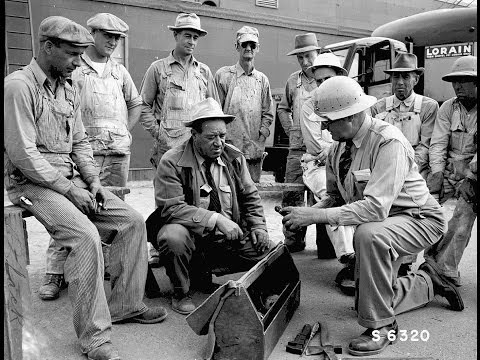

Hanford Construction Camp

B Reactor Tour Manager Russ Fabre describes where the Hanford construction site was located. Harry Kamack, who worked at the T Plant during the Manhattan Project, recalls what it was like to eat in one of the gigantic dining halls.

Russ Fabre: The Hanford construction camp itself was two miles wide. That’s from the Columbia River up to our Route 6 highway. From our highway to our right here, three miles in depth downriver. That was the construction camp. Again, over 50,000 workers, eight mess halls.

Narrator: Harry Kamack was a chemical engineer who worked at Hanford’s T Plant, and remembers the massive dining halls.

Harry Kamack: The dining halls they said could handle and feed 10,000 people at a sitting. The way that it worked when we ate there was, you filed in. There were great long tables and you sat as you came in, in a bench along the table. There were great big bowls of food on the table, which were passed around and you helped yourself.

When a bowl became empty, somebody would hold it up and there were these workers, mainly women, running around. They would grab it, put a new bowl down on the table. As soon as you finished eating, you got up and moved out. They would grab the place, the knives and forks, and put down new.

So it was an assembly line. It just worked very well. And the food was very good and plentiful.

Larry Denton remembers what life was like during the Manhattan Project at Hanford, and how different it was from life in rural Idaho.

Narrator: As young man from northern Idaho, Larry Denton was astonished at the sheer magnitude of Camp Hanford with its 50,000 people coming and going day and night.

Larry Denton: I was living in northern Idaho and working in a lumber camp. I called my father, who was down here working as a patrolman. He said, “They’re hiring, so come on down.”

I was assigned a clerk’s job, which was called a shipping clerk, but I was receiving and issuing welding gases. We issued somewhere around a million containers of helium and oxygen gases.

We were totally amazed at all the stuff that was coming in. The stuff that was going out was never used, so we weren’t producing anything. We didn’t know what was happening.

One of the things that I couldn’t understand: as a boy out of northern Idaho, I’d never been around black people. They had black people segregated from the whites. That didn’t make sense to me.

They built a big theater and big rec hall for our entertainment, and we had outdoor theaters. They weren’t too good sometimes in windstorms, in the outdoor theaters. You had to sit there with goggles on to watch a movie, but it was something to do. Then we could walk up to White Bluffs and get an ice cream cone. Why, it was only two miles.

It was an amazing experience for a man from northern Idaho to come into a camp of 50,000 people going day and night. The big mess halls, meal tickets were almost nothing. Wages weren’t very much, but they were great then: a dollar an hour, six days a week, ten hours a day. It was a lot of money to us.

R Reactor Tour Manager Russ Fabre and Manhattan Project veteran Larry Denton describe the Hanford construction camp’s massive size and facilities.

Russ Fabre: In 1943, when the government came in and took over the Hanford town site, which is where we are at right now, in its place they built a construction camp known as the Hanford construction camp. The numbers associated with that are absolutely amazing. During the interview process alone, they interviewed over 225,000 candidates.

That was to fill, depending upon the sources, between 45,000 and 53,000 work positions out here. In order to house those people, you needed barracks. You needed trailers. And you needed all of the support structure to feed and house those workers.

Narrator: Larry Denton, who worked at the B Reactor as a reactor operator during the Manhattan Project, remembers the immense construction camp and the facilities needed to support the massive workforce at Hanford.

Larry Denton: The construction camp was phenomenal, as far as I was concerned. It housed 40,000 construction workers in barracks, another 10,000 in the trailer camp. They had no facilities, really, to take care of things like this, so they brought in railroad engines and parked them along the railroad track. The Milwaukee Railroad was extended down into the town of Hanford. The barracks were heated by steam, and these railroad engines provided the steam for the heating of the camp.

We had a hospital—I think it was a sixty-room hospital. We had a big administration building, men’s barracks, and women’s barracks. Women’s were segregated from the men in both cases, blacks and whites. We had a grocery store. And, like I said, they had that big rec hall. We had some of the best orchestras in the world came and entertained for us.

Steve Buckingham, who worked at Hanford for many years, describes what everyday life was like during the Manhattan Project, and how the desert belied what many workers had expected of the Evergreen State.

Steve Buckingham: The War Manpower Board dictated where you could recruit, because in wartime, you just couldn’t go over to the coast and recruit people from the shipyards or Boeing over there. So a lot of recruitment was done down South, because the South wasn’t highly industrialized in the ‘40s.

They were given a railroad ticket. I have to always kind of laugh because the trains came through Pasco, where the railroad station was located, about two o’clock in the morning. I’m sure if it had come by during the daylight hours, they wouldn’t have bothered to get off the train. Because the recruiting posters were really funny. “Come to the Evergreen State of Washington. Sparkling rivers! Snow-capped peaks! Wonderful fishing and hunting!” What do they come to? They come to a desert.

At the peak of employment, there were 55,000 people. It was the fourth-largest city in the State of Washington. People lived in barracks. The women’s barracks was on one side of the camp, surrounded by a barbed-wire fence. Because they were recruiting girls right out of high school to come here to work as waitresses, secretaries, clerks, they decided they needed to do something to kind of protect these girls. So they hired a Mrs. Marris.

She was dean of women at Oregon State College. She organized a lot of things like sororities, scout clubs. She would organize shopping trips for these women, because here they were, living out here in the middle of nowhere. The nearest store of any reasonable thing was eighty miles away. It made life a little bit more tolerable.

They built an auditorium. It held 5,000 people. It took seven days to build this auditorium. Big name bands came here and played. Jimmy Dorsey, Ted Weams, Kay Kyser played here.

They built a big tavern. At that time, the only thing you could drink in the State of Washington was three-two beer, 3.2% alcohol. They opened a brewery over in Walla Walla. Pioneer Beer wasn’t all that great, but it was beer.

At that time, also in the State of Washington, you had to sit down to drink. So people would get off work, rush to the tavern, claim chairs. and then auction their chair off to the highest bidder. Somebody was always trying to make a buck somehow or other.

Many people who came here had never received a paycheck before. Their board and room was taken out of their paycheck, and they left here with thousands of dollars of uncashed paychecks. Everything was paid for, essentially. So it was an interesting life.