Hanford Downwinders’ Struggle for Justice

“Downwinders” are loosely defined as those individuals that lived “downwind” from nuclear production facilities or nuclear test sites. In the United States, Downwinder communities exist primarily in the Pacific Northwest and intermountain range between the Cascades and the Rockies, in states like Nevada, Utah, Washington, Idaho, and New Mexico. Downwinders also exist at former Manhattan Project sites including, but not limited to, Oak Ridge, Fernald, and Rocky Flats, where airborne radiation was released offsite. Due to American atmospheric nuclear testing, Downwinder communities also exist throughout the Marshall Islands. Trisha Pritikin talks about her experience as a Hanford Downwinder and the health complications she developed as a result to being exposed to Hanford’s airborne and riverborne radiation.

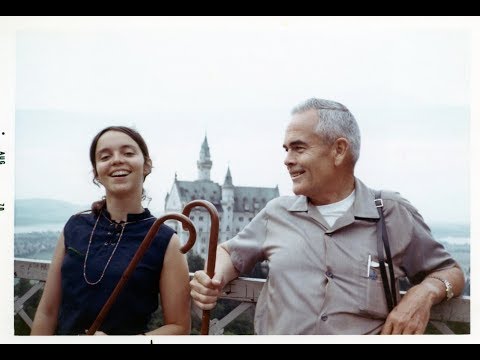

Narrator: Trisha Pritikin was raised in Richland, Washington. She is a Downwinder, a name given to people who were exposed to radiation from nuclear production facilities or test sites. When she was eighteen, Trisha began to experience the first symptoms of an autoimmune thyroid disorder along with other health complications. Here, she talks about the Downwinders in the Hanford area and the beginnings of her personal health issues.

Trisha Pritikin: People downwind, people in Richland, Kennewick, and Pasco, which were the three cities next to Hanford, and people through a vast downwind area were exposed to airborne radioactive particles. The communities down the Columbia River also got a lot of radiation from the stuff dumped into the Columbia River, which went all the way down to the mouth of the Columbia in the Pacific.

The exposures to children were primarily, but not exclusively, through the milk pathway. When babies were fed milk or milk products, or infants had dairy products, radioiodine was contained in those products. It had come out of the chemical separations areas, gone into the air—this is I-131 primarily, but also some of the other radionuclides of radioiodine. It deposited on the pasture grass, and the cows and goats consumed it, and it made its way into the milk supply. That was one of the primary exposure routes for a lot of the people there in the Tri-Cities and downwind.

What I was starting to experience when I was eighteen was the results of those early exposures. My thyroid was shutting down. That’s why my weight was going up and down, and my hair was becoming kinky and not kinky. Then I felt sick, and I started to get tired. That’s a latency period that happens before you feel these effects of exposure. The latency period for me had been from age ten to about eighteen. So eight years after the end of my exposures, I started to get sick. But nobody knew why I was getting sick, because there wasn’t any information about what had happened at Hanford until 1986. This was about 1968, so no one had any idea what was wrong with me.

I suffered a great deal, and kept getting sicker and sicker. I developed cat-scratch fever, which is very rare. It makes you very sick. I had a big tumor on my neck. When I went to the health clinic, they said that it’s only in people with damaged immune systems that they see this disease, because most people can resist it. Can’t figure out where I got it. Took me months to get over it.

Eventually, I recovered, but I was getting tireder and tireder, and starting to have muscle contractions. All these bizarre things were happening. The health center didn’t have any idea what was wrong, because we still didn’t know about the Hanford releases, had no idea.

Narrator: Later, Pritikin was diagnosed with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, a severe autoimmune thyroid disorder. She also has other health issues that she believes are related to her childhood exposure to Hanford radiation. After getting her law degree, Pritikin became a leading advocate for Downwinders who suffered from chronic health problems.

Trisha Pritikin and 3,000 other Hanford Downwinders sued former Hanford contractors in 1991 for the cancers and other potentially radiogenic diseases they developed as a result of exposure to Hanford’s decades of secret radiation releases to the air and waters of the Columbia. The mass toxic tort litigation dragged on over more than 24 years. Tom Foulds was one of the lawyers who represented the Hanford Downwinders.

Narrator: The Hanford Downwinders initiated one of the first federal public liability actions under the Price-Anderson Nuclear Industries Indemnity Act. The Act indemnifies contractors for liability for injuries caused by Department of Energy nuclear facilities. It also specifies that people should receive prompt, adequate compensation for injuries following a “nuclear incident” at any US nuclear facility. Trisha Pritikin describes the obstacles faced by the Downwinders and the results after 25 years of litigation.

Trisha Pritikin: This was, I think, one of the first cases filed under Price-Anderson, using the public liability cause of action, which was created right before the case was filed. It’s a new way of suing if you’re an injured person.

Because there are indemnification agreements for all the contractors that ran Hanford, or in all the other sites around the country. Which means if a company like DuPont or GE agreed to run this very potentially hazardous site, where they’re producing one of the most dangerous substances known to man, plutonium, that they would be indemnified if anybody down the line sued for personal injury. They were indemnified by the US government. And then, they would run the plant under those indemnification agreements.

The reason that’s relevant is that in this litigation, the plaintiffs’ counsel—who only had a certain amount of funding, just whatever they could get—were facing $80 million worth of defense costs being poured into the defense for the contractors under indemnification agreements. It was called a “scorched-earth defense.” It was just all-out, “We’re going to defeat these Downwinders, no matter what.”

That defeats the intent of Price-Anderson. One of the intents of Price-Anderson was to provide compensation to people injured by nuclear sites like Hanford, when those cases merited compensation. Not to put the entire money of the Treasury, including the Downwinders’ own taxpayer dollars, into the defense against our own claims.

Narrator: By 2015, all of the Hanford Downwinders’ personal injury claims were either settled or dismissed. Tom Foulds, one of the lawyers who represented the Hanford Downwinders, reflects on the actions of Hanford contractors and the government at the time of Hanford’s offsite releases. Trisha Pritikin reflects on the outcome of the litigation.

Tom Foulds: The case should’ve been tried, period. I feel that the remedy that was obtained was something that you could live with, with regret. Because the case should have been tried.

Their conduct was a lot more than just being responsible for the releases that came out. There was a great deal of outrageous conduct on their part. They knew, for example, over periods of time, that they were releasing excess amounts of radiation.

They took no steps to warn the public, which they could’ve. They could’ve put everybody on a non-radioactive iodine diet, which would’ve made a tremendous difference. They could’ve done a number of things.

I thought their conduct was really outrageous. Knowing what they did and knowing that the releases that they were permitting were certain to cause disease troubles. They knew that empirically. They knew that it had already happened to the sheep.

Narrator: Trisha Pritikin looks back on the outcomes of Downwinder litigation.

Trisha Pritikin: A lot of the people who did get at least small settlements in the litigation had other cancers, as well as thyroid cancer. They could only get compensation if they had thyroid cancer, thyroid nodules, or leukemias, if they lived on the river, and a couple of other cancers, which are river cancers.

The other people didn’t get any compensation, because there was no way to establish the causal link between their disease and the radionuclides.

A lot of people died during the litigation, or gave up. One lady committed suicide, because she couldn’t wait any longer. Left a note saying, “I can’t wait any longer. This litigation has gone way too long.”

That’s not justice. That’s not what Price-Anderson intended. They intended efficient compensation for those who merited compensation after exposure from a nuclear incident. Price-Anderson’s intent was not fulfilled by this litigation.

Narrator: Author Steven Olson reinforces the Downwinders’ sense of injustice in his book, “Hanford.” As Olson observes, “The Chicago-based law firm that the government hired to defend itself against the lawsuits made tens of millions of dollars—substantially more than the plaintiffs received.