Health and Environment

During World War II, the health effects of different levels of radiation exposure were poorly understood. Gordon Garrett believes that his father’s health was compromised by radiation exposure during his work at the Y-12 Plant.

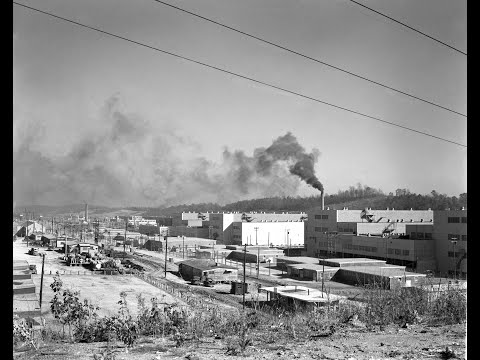

Narrator: Merrill Garrett worked at the Y-12 Plant during the Manhattan Project. He and many of his coworkers believed radiation exposure shortened their lives. Merrill’s son Gordon grew up in Oak Ridge in the 1940s and 1950s and shares memories of his father.

Gordon Garrett: He’d come home, and his badge would be red, because he had too much juice that day. They’d tell him to go take a shower, go home for a couple of days, and when the red goes off, come back in. You know that was far and away not what they should have done. They should have had shielding and stuff on but they didn’t know about that in those days. He and a lot of other men paid a price in their health and had their lives shortened because of the work that they did there. But I don’t think they would have done it any other way. I think they all felt like they helped shorten the war. They saved some lives and they were happy to do it.

Between 1945 and 1947, a series of experiments at four hospitals around the country involved injecting plutonium or other radioactive elements into a total of 30 humans to study the effects. In Oak Ridge in April of 1945, doctors injected an African-American man named Ebb Cade without his consent. To learn more about the experiences of African-Americans on the Manhattan Project, including racial segregation in Oak Ridge, click here. For more on the human radiation experiments, click here.

Narrator: The Manhattan Project helped doctors better understand the effects of radioactive materials on the human body. From 1945 to 1947, at four different hospitals around the country, patients received plutonium injections without their consent. An African-American construction worker, Ebb Cade, was injected in April 1945 at an Oak Ridge Hospital. Author Denise Kiernan describes the so-called “plutonium files.”

Denise Kiernan: I came across the files related to plutonium research and research into the effect of plutonium on human beings. And there was a black construction worker who was coming into work at K-25 one morning who got in a car accident—he and the guys in the car with him—there was a car accident about a mile away from K-25. And he was taken to the hospital and he had a broken leg among other injuries.

Instead of having his leg set immediately, they injected him with plutonium without his consent. And they wanted to track that plutonium, and see where it went through his body, which is why they did not set his leg immediately. And they would take urine and feces samples at certain intervals. They wanted to see whether or not it had penetrated his teeth. So, they removed–I think it was fifteen of his teeth–to see if it had gone there. So, that testing was something that I was really, really, bowled over and shocked by.

And a lot of this information just became available in the ‘90s. There was a [Advisory] Commission on Human Radiation Experiments under, I think, it was during the Clinton Administration. And they said, “We want all of these records out. We want everybody to be able to look into them.” They interviewed a lot of the doctors who were a part of it and released as many files and as many papers as they could.

Eric Pierce, senior scientist and leader of the Earth Sciences Group at ORNL, traces the environmental effects of the weapons production of the Manhattan Project and Cold War, and details how his group’s research has expanded.

Narrator: Eric Pierce is a senior scientist at Oak Ridge National Laboratory and leader of the laboratory’s Earth Sciences Group, which deals with uranium contamination and other environmental challenges.

Eric Pierce: It’s [the Earth Sciences Group] really born out of a legacy of just the history of nuclear weapons production. DOE has a number of sites across the complex that are impacted as a result of weapons production.

The Department of Energy has had a long history, one of understanding how those materials move through the environment, but, more importantly, how do we address the legacy, contamination legacy, that exists. And what my group does, primarily, is provide that foundational knowledge that enables the Department to address those issues in a safe manner.

The division has had a long history of doing that kind of work. And that has transitioned into “How do you use water to produce energy?” and “What’s the impact of that use of that water on many of the aquatic resources that we have across the country?” To understanding how an evolving environment may release a certain amount of CO2 and/or methane. A long history in doing work on understanding “What’s the impact of acid rain on our terrestrial ecosystems?”

In particular, for the Earth Sciences Group, we have a long history of studying just subsurface migration of energy byproducts. And that ranges from trace metals such as mercury or lead or cadmium or cobalt, which you can also have variations radionuclides that are variations of those.

But also, understanding how uranium, for example, migrates through the environment in subsurface systems. Uranium is a primary product of nuclear weapons, in general, and a primary product of much of the nuclear energy that we produce across the country. And as a country and as a nation, we have a responsibility to store that material for long-term storage and disposal. And so, understanding how uranium moves through the terrestrial environment has been a long history within the Earth Sciences Group, in general.