High-Speed Photography

Manhattan Project photographer Berlyn Brixner describes one of the high-speed cameras he used to record explosives tests.

Narrator: Photographer Berlyn Brixner remembers joining the Manhattan Project, and he describes one of the high-speed cameras used.

Berlyn Brixner: Well, when I was interviewed by Professor [Julian] Mack, he pulled out a drawing of a high-speed camera, which he had invented and was having made. He said I was to operate that camera. I said, “I’d be very interested in doing that.” The camera was to photograph the explosions.

The camera was a slit camera or chronograph type of camera, sort of like these cameras that are used for horse races to photo finish, take the photo finish. Only it had a rotating mirror in it that swept the image of the slit around the film, and so it was much faster than the ordinary photo finish cameras.

You imaged the object, which was an explosion, to be on the slit of the camera. Then that image was relayed to the film and that moved along the film, so that as light appeared in that slit, it was recorded on the film. And in that way, the physicists could tell what was going on in the explosion. It worked out beautifully.

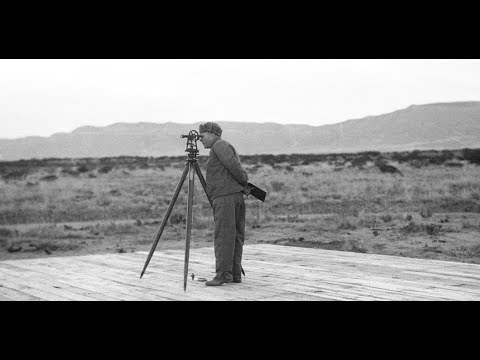

Manhattan Project photographer Berlyn Brixner recalls setting up 50 motion picture cameras to capture the Trinity Test.

Narrator: Manhattan Project photographer Berlyn Brixner describes photographing the Trinity Test, the world’s first nuclear explosion. Some 50 motion picture cameras were aimed at Ground Zero, where the explosion took place.

Berlyn Brixner: Kenneth Bainbridge put my boss in charge of the overall photography at the Trinity Site. My boss then put me in charge of the motion picture part of the photography. I finally got as many as nearly fifty cameras, motion picture cameras, in operation or ready to operate by the time of the explosion.

We had two sites north of the Zero and two sites west of the Zero, one at 800, one at 10,000 yards. They got rather a complete record of the explosion from the first ten-thousandth of a second.

I had lot of these Fastax cameras running at the near site until something like a minute or more after the explosion. So we got a complete record with those motion picture cameras of the whole explosion, something like 100,000 pictures were taken. The pictures that you look at, almost all of them are taken from the frames of those motion picture cameras.

Manhattan Project photographer Berlyn Brixner recalls being stunned by the large explosion of the Trinity Test.

Narrator: Manhattan Project photographer Berlyn Brixner remembers the critical moment surrounding the Trinity Test.

Berlyn Brixner: Well, I was sitting at one of my cameras, motion picture cameras, which was on a panoraming device. I was just sitting there with the camera running. Everything was operated from the central control station. So I didn’t have to do anything at the time but just sit there.

I had a loudspeaker actually and was listening to the countdown, and so I knew when the explosion was to occur. I had arranged a very dense welding glass type of glasses in front of my eyes, and I was looking directly at the Zero. I was one of the few people allowed to do that. It was perfectly safe through these welding glasses. I was looking right at it, just staring at where it was.

Of course, it was nighttime. I couldn’t see anything. But when the explosion went off, that welding glass seemed to just glow white, just intense white like the sun. So it just blinded me, and so I looked aside to the left. The Oscura Mountains were at the left, and they were just lit up like daylight then. So I looked at that for a few seconds, and then I looked back through my welding glass and I saw that the terrific explosion had taken place. Just unbelievably large explosion.

My camera was just sitting there, but soon the ball of fire was starting to rise and I thought, “Gee, I better get busy!” So abruptly I raised it, and photographed the ball of fire as it went up to the stratosphere. I kept photographing it for the next couple of minutes or so.

I knew immediately that the explosion had exceeded the greatest expectations and that essentially we had won the war, because that bomb would soon be used on Japan. And it was. That was July the 16th, I believe, and the war was over only about three weeks later.

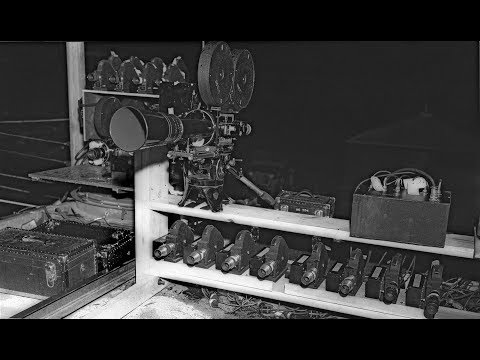

Manhattan Project artifact collector and expert Clay Perkins describes the Marley camera, which was used for some Manhattan Project explosives tests but was out of date by the Trinity Test.

Narrator: Manhattan Project artifact collector Clay Perkins discusses the high-speed Marley camera, which was used at Los Alamos but was out of date by the time the Trinity Test came around.

Clay Perkins: There were commercially available cameras that would run up to maybe 10,000 frames per second. That’s 10,000 individual pictures in one second. That’s very fast. They are called the Fastax.

They wanted to see many of the development steps of the bombs, and of course, then the actual explosion of the bomb that was tested at the Trinity Site in New Mexico, in more detail how things developed.

They found that there was a camera in England called the Marley camera—based on the name of the man who invented it and assembled it, used it for other things—and brought the Marley camera over here to take pictures of the Trinity Test.

These things worked with a spinning wheel of little slots in front of a mass of individual cameras, so to speak. One piece of film, but with multiple lenses. The geometry of that allowed pictures to be taken up to 100,000 frames in one second, which of course is getting pretty interesting. You got a bomb that probably most of it or all the reaction occurs in less than a second. Now you can cover the whole thing pretty well.

That camera was going to go down to the Trinity Site and be a very important piece. Well, other people had been working on high-speed cameras, too. By the time of the Trinity Test, the Marley was out of date. It was not used. It was used for other operations in the developmental process, but it wasn’t used for the famous first explosion.