Jones Laboratory

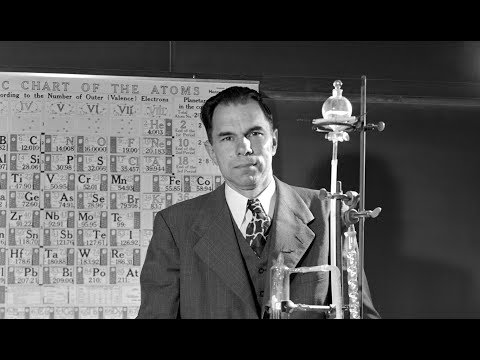

Physicist Peter Vandervoort and Manhattan Project chemist Glenn Seaborg describe Seaborg and his team’s work to isolate and weigh a sample of plutonium in Room 405 of Jones Laboratory.

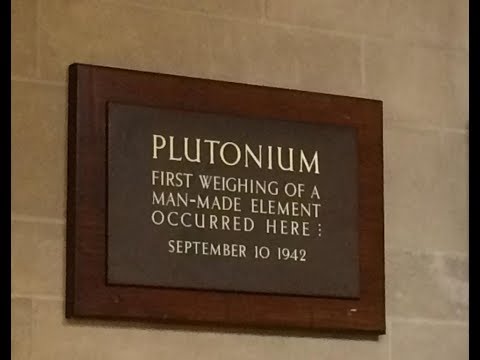

Narrator: Jones Chemical Laboratory is most famous as the site where Glenn Seaborg and his colleagues first weighed a sample of plutonium. Room 405, where they worked, is now a National Historic Landmark. Peter Vandervoort remembers.

Peter Vandervoort: The George Herbert Jones Chemical Laboratory was completed around 1928. It was on the fourth floor of Jones that a team led by Glenn Seaborg first weighed the very tiny sample of plutonium that had been produced elsewhere. It’s a kind of benchmark in the chronology of the Manhattan Project and the Metallurgical Lab.

Narrator: Glenn Seaborg recalls his work isolating plutonium in Room 405.

Glenn Seaborg: Actually, the first isolation of plutonium took place in August and September 1942 while we were still in Jones Laboratory. The room in which those ultra-microchemists worked was a very small room; it was only about seven or eight feet wide and maybe ten feet long.

We worked six days a week and came back every night, five nights a week—that is Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday nights—either to the laboratory or to some kind of a meeting, and then had another coordinating meeting that ran all day all Sunday morning. That was our schedule.

Historian Alex Wellerstein introduces Plutonium, the element named after Pluto, a far-out planet and the Roman god of death.

Narrator: When it comes to cool new advances, nuclear science has always boasted some of the most far out discoveries. When the heaviest element found in nature was discovered, the farthest away known planet was Uranus, and so the element was named “Uranium.” By the time an element heavier than uranium was created, there was a new farthest out planet, Neptune, and “Neptunium” was born. And by the time they discovered an element heavier still, Pluto still held planetary status and we had “Plutonium.”

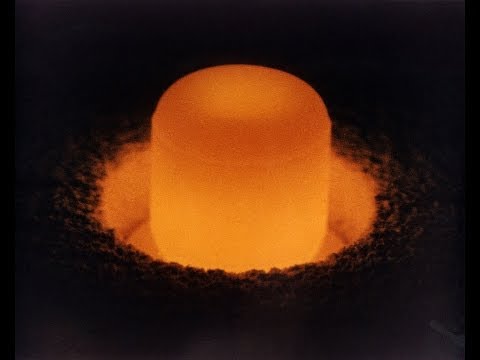

Alex Wellerstein: Plutonium is a manmade substance. It is an element that generally speaking does not exist in nature. It is just stable enough to be something we can keep around, but it is also just unstable enough that we can use it inside a nuclear bomb. It is really tricky metal, probably appropriately named plutonium for Pluto, originally a planet but also the Roman god of death.

Narrator: Plutonium is prone to both chemical and physical changes with shifts in temperature. And it is both radioactive and toxic. What is more, it is pyrophoric, meaning it can catch fire when it is exposed to air.

Alex Wellerstein: Glenn Seaborg, when he discovered it, gave it the atomic abbreviation of Pu, not Pl. And it was partially as a joke because plutonium was so difficult and somewhat nasty to work with. So it is “P-U.”

Narrator: Of course, plutonium was essential to the wartime bomb effort, and despite its challenges it continues to find useful applications today such as fueling space exploration vehicles like the Curiosity Rover sent to Mars. After all these years, plutonium is still one far out element.

Glenn Seaborg recalls luring scientists to join the Metallurgical Laboratory. Larry Bartell remembers being interviewed by Seaborg – and relates how the future Nobel Prize winner got him out of his final exams.

Narrator: Recruiting young scientists to work on the top-secret project could be a problem. Glenn Seaborg explains his approach.

Glenn Seaborg: I had trouble getting recruits. I would write to a young fellow at a university, and he would write back that he was doing something important. I don’t know, he was synthesizing an anti-malarial compound or something, you know, another one, and he just couldn’t come. I would write back, and I couldn’t tell him. I would write, “Just trust me.”

It was very often my people I’d met earlier in life—schoolmates at UCLA or something like this. I can remember writing back, “You just come. We’re working on something that’s more important than the discovery of electricity.”

This almost always brought them. “My God, more important than the discovery of electricity?” So they’d turn up.

Narrator: Lawrence Bartell was still a student at the University of Michigan when he interviewed with Seaborg for a job at the Met Lab.

Lawrence Bartell: When I went [to Chicago] early in 1944, I was interviewed by Glenn Seaborg himself. The interview seemed to have gone well enough, so he said, “I’ll give you a job. When can you start?”

I said, “I can start today except for one detail. Next week I have my final examinations in my senior year.”

He said, “Wait here a minute,” and he disappeared. He came back with a big grin on his face. He said, “I’ve relieved you of having to take any of those final exams.” So I did start that day.