Moral Responsibility of Scientists

Dieter Gruen fled Nazi Germany at the age of 14. After studying chemistry at Northwestern University, he joined the Manhattan Project at Oak Ridge, Tennessee. He went on to receive his doctorate from the University of Chicago and worked as a scientist at Argonne National Laboratory.

Narrator: Dieter Gruen describes how atomic science dominated the news after the end of World War II and how the Manhattan Project was a formative experience.

Dieter Gruen: After the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs were dropped and the war was over, it’s very hard to reconstruct the feeling that existed in this country. People talked about atoms as if that was something totally new, and mysterious and secret. You talked to a person on the street about atoms, and they were all a dither. It’s very hard to reconstruct the intense feeling people had from one day to the next about atoms and atomic science.

One of the messages that we had was that there are no secrets about atoms and that there is no defense against atomic weapons. So we started an organization called The Oak Ridge Engineers and Scientists. We wanted to create public awareness of what urgency there is in preventing anything like this from happening again.

My work at Argonne [National Laboratory] was strongly influenced by my experiences on the Manhattan Project. On reflecting back on what I did during most of my life, I would have to say that my scientific work had its origins in the realization that nuclear power was something really new and important. And that there were two sides to it: one destructive and the other constructive, and that that power could be used as a non-polluting alternative source of energy. So for the rest of my scientific life, I devoted myself to the solution of this very daunting and challenging problem of how to create a sustainable, non-polluting global energy source.

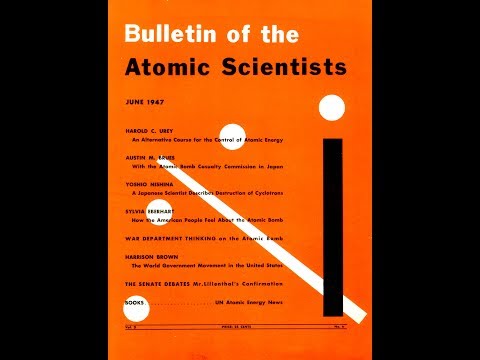

The influential journal and nonprofit organization the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists was founded by Manhattan Project scientists at the University of Chicago who believed they “could not remain aloof to the consequences of their work.”

Narrator: Rachel Bronson, executive director of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, and Kennette Benedict, former executive director, describe the founding of the Bulletin in the aftermath of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Rachel Bronson: What our founders understood at that time, back in the late ‘40s and early ‘50s, was that science was advancing so quickly, and was going to have massive consequences on the health and safety of this planet. It’s that big. Big, existential issues. In 1945, that was nuclear weapons, but they understood that science was going to bring other big challenges, and that if we could manage the risks presented by science, we could accrue the benefits. But if we just enjoyed the benefits, it was going to a very dangerous and really unhealthy planet.

Kennette Benedict: They all loved the science. It was a heady time for physicists. I think after seeing how this bomb was used and how indiscriminately it could kill so many thousands of people, I think they felt that they weren’t quite sure whether they’d done the right thing. So, it was a very difficult time here.

I think many of them understood this is a weapon of genocide, and that was really a horrifying thought, especially given the fact that World War II had just seen the most genocidal mass slaughter of six million people. And, obviously, they didn’t want to be part of that.

In the pages of the Bulletin, I think you’ll see some of the wrestling with conscience that many of these scientists were engaged in, and used the Bulletin as an outlet for that discussion.

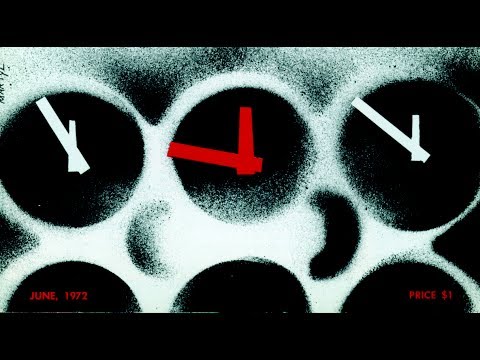

In 1947, artist Martyl Langsdorf, the wife of Bulletin co-founder Alexander Langsdorf, designed the famous “Doomsday Clock” for the cover of the magazine.

Narrator: Kennette Benedict explains the origins of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists’ iconic doomsday clock, a symbol designed to warn the public “how close we are to destroying our world with dangerous technologies of our own making.”

Kennette Benedict: They turned to their nearest neighbor, Martyl [Langsdorf], to come up with a design for the cover.

She thought about putting on the cover a uranium symbol, lots of different things, but came up with the idea of a clock, because she had also been part of these discussions on campus, and felt the urgency that the scientists were expressing. They were very worried that the president and politicians and military people would see this as something that they could use to their advantage, and they really wanted the public to know.

They also saw that secrecy was how the bomb was born and secrecy would keep the bomb from being understood by the broad public. This urgency is what she wanted to represent. She came up with the fourth quadrant of the clock and, as she said, “Well, I set it at seven minutes to midnight. I mean, it just looked good.”

Narrator: Every year, the Bulletin resets the doomsday clock. How close are we to midnight now?