Oak Ridge Innovations

At Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL), scientists from a variety of fields collaborate to solve global challenges. Adam Rondinone experiments with energy storage using nanotechnology, while Budhendra Bhaduri examines population changes on a global scale.

Narrator: The Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) had lots of brilliant minds, but it was creativity and collaboration that helped scientists join to tackle nuclear science’s most complex problems. ORNL scientists Adam Rondinone and Budhendra Bhaduri describe this convergence.

Adam Rondinone: Everybody in science is kind of unique. We’re all like artists. And so, one artist might be able to paint a certain type of painting; another artist can paint a different type of painting. And this creativity and this vibrancy is really what allows us to generate new ideas on a continuous basis and pursue those ideas. So, science really is about facts, it is about careful measurements. It also is about creativity.

Budhendra Bhaduri: I work with a very interdisciplinary group of people. Scientists who have expertise all the way from social science–for example, to geography, anthropology– all the way to people who work with very large computers, a lot of data–like electrical engineers, computer scientists, computer engineers, civil engineers, transportation engineers. Because unless you bring a very interdisciplinary approach, some of these societal challenges are impossible to solve.

“Big Science” is used to describe large-scale scientific projects typically funded by governments. The term has roots in the efforts of the federal government to assemble and subsidize scientists who worked on the Manhattan Project. ORNL physicist Thomas Cormier and electrochemist Adam Rondinone discuss the rise of Big Science and government funding of scientific research.

Narrator: What is sometimes called “big science” was made possible by massive government investments in scientific research. The Manhattan Project was a catalyst for government investments, according to Oak Ridge National Laboratory physicist Thomas Cormier.

Thomas Cormier: What I call “Big Science” actually begins – well, the first example of that is the Manhattan Project. Because prior to that, governments around the world did not invest in science at all. And you had private foundations or universities or whatever investing in science, and that really limited the scope of what you could do. But soon as after the Manhattan Project, it became clear that the way to really get things done is to put the backing of major governments behind certain scientific initiatives. Then, you can see what –– you can land on the moon, you can build the Large Hadron Collider.

So, that really begins with the Manhattan Project. This whole idea of government investing in science really came out of the Manhattan Project.

Narrator: To explain the advantages of government funding of science, this is ORNL electrochemist Adam Rondinone.

Adam Rondinone: Congress funds scientific research in this country with the intent that it’s going to help everybody. And so, the knowledge and the information that we discover, it gets reported and it gets reported in journals. In some cases, we put it out in the popular press. Occasionally, we’ll make a YouTube video and put that on the internet. And the idea behind it is that if the basic knowledge is discovered, then a company or a government or anybody can take that basic knowledge and use it to make some type of an application. So, solve a problem, essentially. Solving problems makes people’s lives better.

Often times, solving a problem gives us new economic opportunities. So, we might be able to found a new company and put people to work. In my case, where we’re looking at nanotechnology approaches to solving energy problems. The expectation is that if we’re wildly successful, ten years down the road we might be able to say, “Instead of drawing energy from fossil fuels, where we have to bring that up out of the ground, we can draw our energy from renewable sources, such as windmills and solar panels.” Well, that’s an opportunity for renewable energy. It’s also an opportunity to minimize environmental impact.

And so, governments fund basic science with the intent of making people’s lives better and making the economy stronger and more competitive.

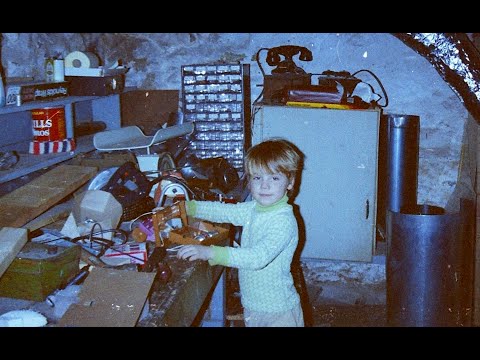

Often encouraged by their parents, many scientists at Oak Ridge National Laboratory became interested in science at an early age.

Narrator: Many scientists were inspired early in life to explore the world. T.J. Paulus’ father let him play with firecrackers, Julie Ezold’s dad expected her to go to college, and Adam Rondinone’s father was a watchmaker.

Adam Rondinone: I was actually born in a somewhat rural town in New Hampshire. And I’ve always loved science, ever since I was a kid. In fact, I inherited my love of science from my parents. I think in a different life, my dad, who was a watchmaker, probably would have been a scientist. He just didn’t have that opportunity. But he was always interested in things that were mechanical and electronic. He taught me about those things ever since I was really just a little child, maybe five, six years old.

And then, at some point when I was a kid, my parents bought me a set of encyclopedias called The Young Children’s Science Encyclopedia. And that was a set of books just filled with experiments that could be done at home, and I did these experiments. I probably did most of them, or the ones I can get my hands on the materials. And that really just fed my love of science. When I went off to college, it was just that was what I was going to do.

Julie Ezold: My sixth grade science teacher was the one who really got me interested in science. I can still remember his lessons. I was also good in math. They started segregating you in sixth grade so that you could be accelerated math, so that you would be taking the advanced placement classes by your senior year. So, I was already on that track by the time I was eleven.

I had an older sister. I had two younger brothers. My dad was very adamant about “You will all get a good college education. You will have employment.” There was no “This is a girl thing. This is a boy thing.” There was “You will do, period.” That made it pretty easy that way.

I got this opportunity to do a summer one-week camp in Lynchburg College in Lynchburg, Virginia. My parents agreed to pack up the camper, and we drove thirteen hours south. So, from upstate New York to southwestern Virginia.

I spent a week. We were the only class that had lab work. So, we got to not only learn about radioactivity, nuclear chemistry, radiochemistry, we also got to do the labs that went with it. So as soon as my dad picked me up from that camp, I was like, “I’m going to be a nuclear engineer.” And he’s like, “Okay, kid.”

TJ Paulus: I was interested, as some boys become, in firecrackers. I found that I could explode them using a battery and a little bitty wire around the wick of the firecracker, plug in the battery, and go “Poof.” With that much fun, I went off with finding a particular kind of firecracker called a “bulldog” that was unique, because you could take the end off of it, and you could get the explosive out.

I took the powder from one, dug a hole—Dad was with me, watching—worked my wire, hooked it to the battery. “Boom!” Made a little bigger hole. I put in the powder from three of them down in this little hole, did it again, and, “Poof,” a little bigger hole. Then, I took the powder from twelve of them and put it down in this hole, filled it up again. “Boom!” Great big hole, rocks, sticks flying all over the place. Dad looked around from behind a tree and says, “I think that’s enough.” So, that was early interest in electricity.

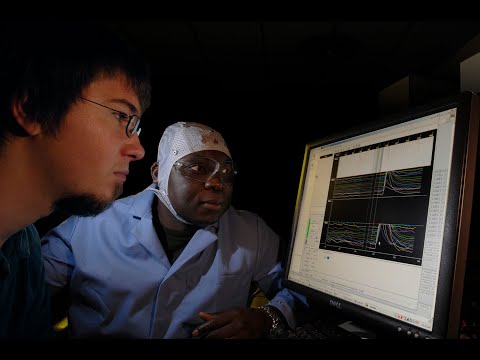

From Nigeria and India, respectively, Justin Baba and Budhendra Bhaduri moved to the United States in the 1990s. Both scientists devote their research to improving the quality of life for people around the world.

Narrator: Oak Ridge National Laboratory scientists Justin Baba and Budhendra Bhaduri are dedicated to making a positive impact on their world.

Justin Baba: I grew up in Nigeria and I had the opportunity to go to American schools. And eventually, I ended up in the U.S. in 1990, to go to college. But my desire to become a scientist actually began in middle school, as I discovered that I was intrigued by the history of what others had accomplished and discovered. And also, I realized I also was intrigued by the human body. I knew, at that point, that I did not want to be a medical doctor. But I thought it’d be kind of fun to do medical-related research that could have an impact on the lives of many people for many generations to come.

My dad’s older brother, in the late ‘80s, was diagnosed with diabetes, and when he was diagnosed, he ended up having his big toe amputated.

My dad heard about it and went and got checked that day and discovered he also was a Type II diabetic. So, that was a huge motivation for me. What can we do to help diabetics?

That, kind of, has been a driving motivation for me–to see what can be done to help diabetics better manage the disease and be more compliant and have a good and fruitful life.

Budhu Bhaduri: I was always inclined to science. I liked science when I was going to school. And then, I remember distinctly they used to have a one-hour program on National Geographic every Sunday afternoon. And I was sort of hooked to that one, and there was this particular one that talked about cleaning up streams in Germany that somehow stuck to me. And It was one of those first big push in the sail in that direction, saying, “You know, I would like to be part of something like that, making a difference for the planet.”