Postwar France

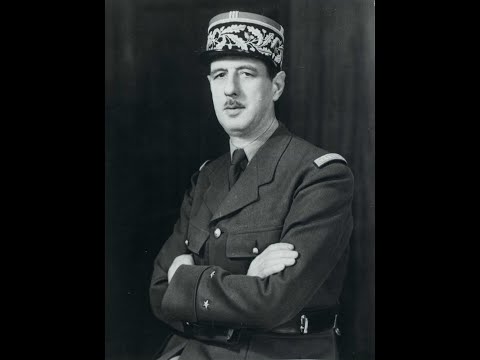

French leader Charles de Gaulle and Frédéric Joliot-Curie had very different political views, but both agreed that France should pursue research into nuclear energy.

Narrator: In 1945, the Provisional Government of France authorized the creation of a government institution for nuclear research to be led by Frédéric Joliot-Curie. Even though Charles de Gaulle, France’s de facto leader, and Joliot-Curie had very different agendas, as Garret Martin explains, they found common ground.

Garret Martin: As soon as the war ends essentially, in 1945, de Gaulle meets Joliot-Curie. They decide to create a Commissariat à l’énergie atomique, or the Atomic Energy Commissariat, a sort of structure in order to continue to build upon the scientific discoveries of the French scientists before the war. I think that became even more urgent once the two atomic bombs are dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

I think for de Gaulle and Joliot-Curie, at least at that time period, there’s a sort of meeting of interests. They don’t necessarily come from the same angle, but I think they have a shared interest in seeing France pursue and develop a nuclear program.

Narrator: Spencer Weart describes Lew Kowarski’s role in the construction of France’s first nuclear reactor, as well as the connection between French nuclear energy and weapons development.

Spencer Weart: Kowarski built their first reactor, ZOE. With the help of a lot of information that he had brought back from Canada, some of which came from the United States ultimately and some of which he had developed himself.

They set to work in the complete chaos and misery of postwar France to set up a new source of energy. It didn’t hurt that France was absolutely devastated. The power went off all the time, if you could even get power. They were short on coal. People were literally freezing in the dark. Getting a new source of energy was certainly a good idea for postwar France. Also, France didn’t have any oil.

The hitch, of course, was that if you build a reactor, then you are building a way to get an atomic bomb. The French, needless to say, were very well aware of this. But as we have seen with many other countries since, you can go a long way saying, “Oh, oh, all we want to do is do peaceful nuclear energy.” Then ten years later, you say, “Oh, look, look, we have all of this stuff around. We can make a bomb with it.” That was basically the route that the French had.

After World War II, the United States did not want to share its nuclear secrets with other countries or non-American scientists. Hélène Langevin-Joliot describes why her father, Frédéric Joliot-Curie, and others believed that science should be shared.

Narrator: The 1946 Atomic Energy Act sought to keep American nuclear research under wraps. The Manhattan Project’s atomic research was considered “classified,” and could not be shared. Hélène Langevin-Joliot explains why scientists like her father, Frédéric Joliot-Curie, objected to nuclear secrecy.

Hélène Langevin-Joliot: It not only is the end of the civilization if we have an atomic war, but it is the end of science if we are not able to have the condition for fundamental research and freedom of ideas all among the world.

A statement by [Albert] Einstein: “Science is international, gentlemen, whether you like that or not.” I like the statement very much.

The diplomats, they were in between two choices. The security of the [United] States relies on the fact that, “We are the first. We have to remain the first, and we build more bombs, or the security of the States will rely us on other countries, on an agreement. And you cannot prepare an agreement when you take steps to war.”

So when the discussion occurs in this commission, diplomats and scientists, I hear my father commenting to my mother, “If scientists were alone, we will find a solution.”

Frédéric Joliot-Curie was a staunch advocate for nuclear disarmament. Spencer Weart describes Joliot-Curie’s involvement in the anti-nuclear movement, and how his outspoken political beliefs led to his firing from the French Atomic Energy Commissariat in 1950.

Narrator: Frédéric Joliot-Curie was not only a scientist; he was also an activist. Spencer Weart talks about the Communist Party’s role in France after the war, and Joliot-Curie’s stand against developing nuclear weapons.

Spencer Weart: The [French] Atomic Energy Commission naturally had quite a few communist people in it. This was not so unusual in France after the war. The Communist Party was a major political party. Many, many Frenchmen were communists. It was not unnatural for there to be lots of engineers and scientists and so forth who went into the Atomic Energy Commission.

Joliot, being a very prestigious person and also a communist, was a leader in the world movement for disarmament, the anti-nuclear weapons movement, very big. Millions of Frenchmen signed petitions. Hundreds of millions of people around the world signed petitions for the abandonment of nuclear weapons.

When he finally definitively said that he would not participate in anything in the Atomic Energy Commissariat that would contribute to building nuclear weapons, he was fired. This was 1950. The Cold War had begun.

A desire to remain a global power and humiliation in World War II, the Suez Canal crisis, and Vietnam motivated France’s leaders to develop nuclear weapons.

Narrator: During the 1950s, the French government moved from developing nuclear energy to building nuclear weapons. Spencer Weart explains how the lasting memory of World War II motivated France to build a bomb.

Spencer Weart: Surely, France would have tried to do something. The countries that didn’t [pursue nuclear weapons], like Germany and Italy and Japan, had been the losers in the war. France had been a half loser in the war. It was kind of touch and go whether it would join with the real losers and not even try to make a bid for nuclear energy, or whether it would go with Britain and the Soviet Union and the United States and try to build up a full nuclear industry.

Narrator: When the Egyptian President nationalized the Suez Canal in 1956, a coalition force including Israel, the United Kingdom, and France invaded the Sinai Peninsula. Political pressure from the Soviet Union and the United States forced the three countries to withdraw. Historian Avner Cohen describes how the Suez crisis and defeat at Dien Bien Phu in Vietnam influenced France’s decision to build nuclear weapons.

Avner Cohen: The Suez crisis was a major turning point. The conviction that France [had] to keep its status, especially after the humiliation that happened in Indochina, especially Dien Bien Phu, when the French had to desert and had so many losses. “If we had tactical nuclear weapons, we could’ve saved those soldiers, we didn’t have to be humiliated.” The view that for a country that used to be a colonial power, even if they’re losing their colonies, to maintain a certain kind of image, they need to have nuclear weapons, was there much before de Gaulle. De Gaulle supported that, and he would develop [it] into the French grandeur. The notion that for the greatness of France, France must distinguish itself with having nuclear weapons.

Narrator: Garret Martin discusses the French military’s bomb-building strategy.

Garret Martin: Would the United States risk New York to defend Munich? Would they take the risk of responding to a Soviet attack with full nuclear reaction?

From the French perspective, there was a sense that if they developed their own nuclear arsenal in which they keep complete control, that they would keep the French finger on the nuclear trigger, to put it very bluntly. They felt that would give them more options.

Expert Garret Martin explains why France was allowed to conduct nuclear tests in Algeria.

Narrator: Garret Martin describes France’s first nuclear test, and tells why France continued to conduct nuclear tests in Algeria after the country gained independence.

Garret Martin: When the French test their first nuclear weapon in 1960, they were only the fourth country to join the club. So there’s also a sense for [General Charles] de Gaulle that it’s prestige by being a nuclear power, it symbolically speaks to France’s importance.

The first test happened on the 13th of February 1960 in the Algerian desert. They picked that location because it was probably quite remote, away from population centers. Although subsequent studies or subsequent evidence that came out later showed that there was a lot of environmental damage and there was a lot of environmental costs to nearby populations.

Now, the question about how were they able to conduct tests after 1962, once the Algerian war came to end and Algeria became independent? The simple answer is that there was a secret annex, there was a secret part of agreement that was not made public, where France was allowed to conduct a certain number of tests over a period of four years after independence. They had the authorization to continue tests at least until 1967.

Today, France is estimated to have about 300 nuclear warheads, but much of the French nuclear arsenal is shrouded in secrecy.

Narrator: Garret Martin and Avner Cohen describe the French nuclear arsenal, and the secrecy surrounding its stockpile.

Garret Martin: So it’s still a key part of the French strategic doctrine and the French deterrence doctrine. As far as we know, the French nuclear arsenal has about 300 nuclear warheads. It’s mostly divided between a sort of submarine force and I think a force that can be used by French bombers.

Avner Cohen: We know something about the submarines and missiles, but it’s very limited. French people, society, don’t ask too many questions. We know much less about France than we know, for example, about the U.K. France, Israel aside, is the most closed [of nuclear-armed nations]. Talking about democracies, western democracies.

The Curie family’s legacy was pivotal to France’s development of nuclear power and nuclear weapons. France is now seeking to reduce its dependence on nuclear energy.

Narrator: Spencer Weart explains the important legacy of the Curie family.

Spencer Weart: It is largely because of Marie Curie and the legacy of Marie Curie through the Radium Institute and Joliot and so forth and ultimately the Atomic Energy Commissariat that France became the country with the most nuclear reactors, the only country that gets 70 percent of its energy from nuclear energy, electrical energy, and has the classic triad of nuclear submarines and missiles and airplanes. It maintains itself, in this sense, on full equality with the other nations.

Narrator: Garret Martin tells why France is trying to reduce its reliance on nuclear power.

Garret Martin: Interestingly though, in recent years now, the last two or three years, an important law was passed in 2015, where the French are trying to sort of move away from this high degree of dependence. There’s a pretty ambitious goal of trying to move from about 75% of energy being supplied by nuclear energy to more around 50% in the timeframe of about 10 to 15 years. There’s concern about the cost, concern about the security of some of the older nuclear reactors, concern also about some of the recent accidents that have happened, of course, including in Japan in Fukushima.

That’s played a big role in trying to sort of reduce some of the level of dependence. And also a desire to try and build up more renewable energy. Currently, France is quite on the lower end when it comes to its renewable energy as compared to its partners of the European Union.

[Photo of protest © Yann Forget / Wikimedia Commons / CC-BY-SA-3.0.]