Preparing for the Test

Manhattan Project scientists decided to test the plutonium implosion bomb design in a remote area outside Alamogordo, NM, over 200 miles from Los Alamos.

Narrator: The explosions in the canyons around Los Alamos grew increasingly louder and more powerful in early 1945. For safety’s sake, the first full-scale atomic explosion was planned for the remote deserts of southern New Mexico, about 240 miles away. Author Jennet Conant tells us more.

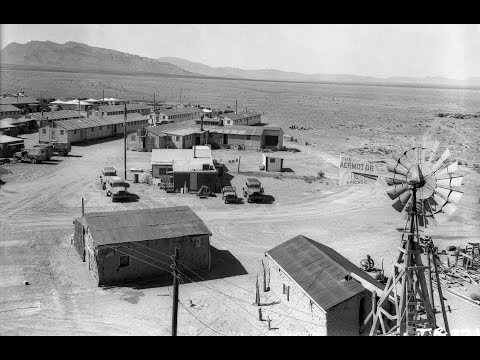

Jennet Conant: When it came time to test this first experimental weapon, they needed a very large amount of acreage and a very remote site. It was a classified weapon. Nobody could know about this test. This was going to be the largest explosion ever conducted by mankind. They had to start looking for a site that was within commuting distance from Los Alamos, because they were going to have to truck the finished weapon, parts, men, and materials. They started hunting around the desert and they found this very remote spot in Alamogordo, just outside Alamogordo, New Mexico. They started building what they call the Trinity Test base camp.

It made Los Alamos look like the Four Seasons. It was really primitive. First, they lived in tents, then in little huts. It was really, really rough. It was all men. They just went in there and hunkered down, and they had to build and complete the weapon there. They then hung it from the steel tower, from which it would be exploded. They built the bunkers and observation buildings where they put all the equipment, very sophisticated equipment, that would measure the force of the explosion and all the different gauges that would do all the different readings for them. The radiation fallout and all of that. Then, bunkers which the scientists could crouch behind for safety.

Looking back, given what we know now, it was horrifyingly close and horrifyingly inadequate protection. Had the wind been blowing the wrong way, they all would have been showered in a fair amount of radioactive dust. But fortune smiled on them that day. Even though it had been a very stormy night and it had looked like they might have to cancel the test, the skies cleared at the last minute and they were able to conduct the test in the pre-dawn hours without incident.

When Manhattan Project leaders decided they wanted to test the plutonium implosion device in the summer of 1945, they developed specific requirements for selecting the test site. They needed an area that was isolated, with few residents, and within driving distance of Los Alamos, NM. Jim Eckles and Manhattan Project photographer Berlyn Brixner describe the process of selecting what became known as the Trinity Site.

Narrator: Manhattan Project leaders had a number of requirements for the world’s first nuclear weapon test site, as Jim Eckles explains.

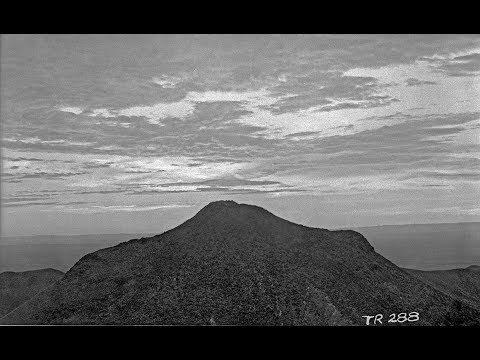

Jim Eckles: The Los Alamos people wanted a place that was isolated. They had a whole series of criteria. They wanted land that already belonged to the government. They wanted very low population densities, close to Los Alamos, close to roads and highways and railroads.

They also looked at two places in the Alamogordo Bombing Range. The Alamogordo Bombing Range was created back in 1942. It was a typical southwestern training range. This was for bombing crews, for B-24s, and B-17s, eventually B-29s. They flew out of what is now Holloman Air Force Base, just west of Alamogordo.

So that land was leased from ranchers, starting in 1942 and it ran up to Tularosa Basin from Highway 70 about, up through Mockingbird Gap in the Oscura Mountains to almost Highway 380, and set aside as a bombing range.

Narrator: Manhattan Project photographer Berlyn Brixner recalls assisting the Trinity Test site selection team.

Berlyn Brixner: We had to get Trinity going. And so, we were first locating, trying to locate a site to do that. Some eight sites had been under consideration. A professor from MIT, Kenneth Bainbridge, was in charge of that. And finally, had in the fall of ‘44 just about decided. Let’s see, the closest site was near Cuba, New Mexico, and the most distant one was down in the Gulf of Mexico on some sand islands there. But he settled on a site south of Grants, New Mexico. And so he said he was going down to look it over before final selection and got my boss and my boss wanted me to come along because I was familiar with the country, having lived and traveled over it.

So we went down there and I immediately found a very bad situation there. It was covered with lava flows. Those flows had tunnels under them that were weak. So it would be very unsuitable as a site for roads and hauling over the big bottle, Jumbo, that they thought they might have to use. So I told him that he should go and look at another site that didn’t have any of these disadvantages and was very easy to use. That was what was called Jornada del Muerto, which is southeast of Socorro, New Mexico. It’s a large flat area and it doesn’t have any trees or lava flows or anything on it. So he essentially took one look at that and decided to take that site, use that site.

Before the Manhattan Project requisitioned the area, the McDonald family owned a ranch in the area. Jim Eckles explains why the McDonald Ranch House was selected as an assembly site for the “Gadget” nuclear device. Manhattan Project physicist Raemer Schreiber recalls the delicate process.

Narrator: Manhattan Project scientists chose McDonald Ranch House an assembly site for the “Gadget” nuclear device. Jim Eckles explains why.

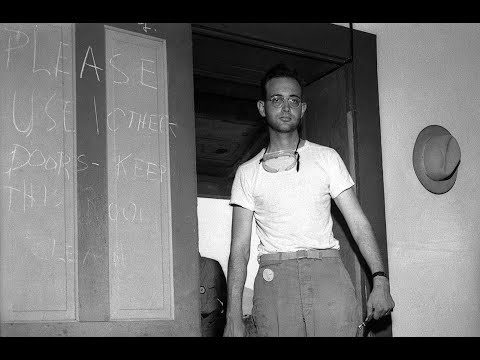

Jim Eckles: The George McDonald ranch house was convenient, because it was the nicest permanent structure close to ground zero. They took the master bedroom and turned it into a clean room. They put plastic over the windows and taped up all the cracks and stuff. There is a sign they chalked on the door about cleaning your feet before entering the room, trying to seal it up to keep dust out of it, for this assembly of the plutonium core.

Most people think, “Well, why wasn’t it blown apart, being two miles from ground zero? Because we have all seen that footage from Nevada where houses are blown apart in nuclear explosions.”

Shock waves do funny things. From the ranch house, you cannot see ground zero. There is a little bit of a ridge. The shock wave may have just kind of bounced over the ranch house. It did knock out the windows to the house and the doors, but the house was pretty much undamaged structurally by the explosion.

Narrator: Ground zero was only two miles away, so this was a good place to bring together plutonium and other components for the “Gadget.” One member of the assembly team was Manhattan Project physicist Raemer Schreiber.

Raemer Schreiber: The first time that the high explosive and the nuclear core got together was actually down at Alamogordo and we did this out in an old ranch house there, at the so-called McDonald Ranch. It was an abandoned homestead. We had moved down everything, diesel generators for electric power, all of the tools and so on. We did the assembly of the nuclear components there, moved them over to the zero point tower and gently lowered the assembly into the hole in the explosives.

Jim Eckles explains why the uranium plug added so much weight to the “Gadget” nuclear device’s core.

Narrator: Coming into the McDonald House, the wooden box with the bomb’s core could be carried in one hand. But when it left, it took two men to carry the box on a stretcher. Jim Eckles explains why.

Jim Eckles: At the clean room, they are going to assemble the core. You’ve got two pieces of plutonium. Herb Lehr is carrying those in a special padded box. There is a famous picture of him coming through the door to the bedroom of the McDonald ranch house.

Lehr is bringing this box in, carrying it in one hand because it only weighs 13, 14 pounds. For a ball of metal that size, it’s fairly dense and heavy, but it’s nothing that you can’t carry in one hand.

So, in the photo where they are loading the core into the sedan to take to ground zero, two guys are carrying the core in a box in on a litter. You’re going, “What’s that about, if it only weighs 14 pounds? I mean, that’s crazy.”

That’s because in there, once they get the core together, they insert that into a uranium plug. This plug is a column of uranium, and it’s got a point in it so you can insert this ball. And so, you’ve got one cylinder then that’s going to slide into the center of the bomb mechanism down at ground zero.

This uranium plug adds a lot of metal to this equation. In fact, it turns out that the plug then, the total plug package, is probably about 120 pounds. And so, that’s why there are two guys carrying it between them on a litter to put it in the back seat of the sedan.

Manhattan Project workers built bunkers around the Trinity Site for witnesses to observe the test, and to hold cameras and instruments that captured key images and information.

Narrator: At the Trinity Site, bunkers were built about five miles away from ground zero. This is where the instruments and cameras were placed, along with eyewitnesses, as Jim Eckles describes.

Jim Eckles: At the site, you get ground zero, and the scientists made the decision that nobody was going to be closer than ten miles outside of a bunker. They built bunkers at 10,000 yards, which was a little over five miles, on the south, west and north basic compass points. People were in those bunkers for the test.

The north and west bunkers were basically camera bunkers, the north one being the prime one for the photos that we see. The motion picture footage and all of those still images of very early stages of the explosion and stuff were taken from the north 10,000-yard bunker.

Narrator: One of J. Robert Oppenheimer’s chief aides was physicist John Manley, who recalls the tiring process of waiting in a shelter for the Trinity Test to begin.

John Manley: I was in charge of one of the three shelters at Trinity. I was at so-called, “West 10,000.” It was a heavily timbered structure with earth piled up over it. I had the responsibility for the people and for the instrumentation in that particular shelter. I remember some of that pretty vividly because the whole thing was such a fatiguing business. From about one o’clock until four or so in the morning, I think that I was the only person awake in the whole shelter. People were just lying on the floor asleep, just dead.

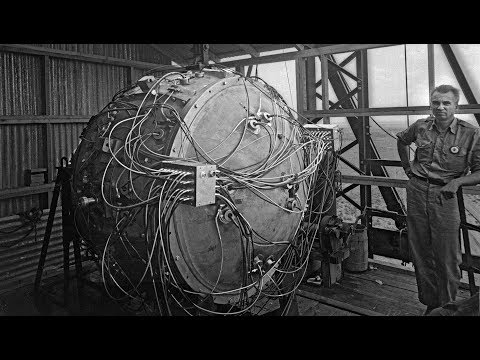

Jim Eckles explains why Manhattan Project leaders decided to detonate the “Gadget” nuclear device from on top of a 100-foot steel tower. Manhattan Project physicist Norris Bradbury, who would go on to become director of Los Alamos National Laboratory for 25 years, describes his job protecting the Gadget after assembly on the tower.

Narrator: Rather than drop the bomb from an airplane, scientists detonated the “Gadget” nuclear device after lifting it up, as Jim Eckles describes.

Jim Eckles: For the test, the decision was made to place the bomb on top of a 100-foot steel tower, not drop it.

Now, the steel tower was built to support this heavy bomb, because the bomb is composed of this plutonium core, which doesn’t weigh much. It’s got a heavy uranium sphere around it. Then there is 5,000 pounds of explosives around that, and then a steel casing around that, a small one. This thing is pretty hefty. They had to raise it up and put it on top of the tower.

Now, the reason they did it on top of the tower was because they wanted to maximize the shock wave, the blast effect on the ground.

Narrator: Sabotage was a very real concern. So, in the quiet hours before the test, one lonely sentinel stood atop the tower to make sure no one came near the “Gadget.” That guard was Norris Bradbury.

Norris Bradbury: My personal concern with the Trinity shot was to get that Gadget assembled up on top of the tower, and assemble it on top of the tower. I assembled it at the bottom of the tower, and then get the detonators on it and get them hooked up, and then make sure than nobody monkeyed with the pesky thing while I had control.

I sat there. Up until it was clear that nobody else was going to be allowed on top of the tower. I would not let anybody come up unless I was there, because I didn’t want anybody monkeying with it. I was responsible for that thing. Even inadvertently, somebody might brush against it, you know, so I stayed there until the ladder was blocked off.

Jim Eckles: Of course, that tower was vaporized in the explosion. A lot of people come and they don’t understand that. They think it was just blown to pieces. It was turned to gas. It was sublimated from a solid to a gas in a fraction of second and joined the fireball going up.