Race Relations

African American scientists faced discrimination and pressure as “representatives” of their race. Physicist Ronald Mickens elaborates on how his friend, J. Ernest Wilkins, combated prejudice and garnered respect by achieving higher standards than his white peers.

Narrator: Physicist Ronald Mickens explains how black Manhattan Project scientists like J. Ernest Wilkins dealt with discrimination.

Ronald Mickens: Their way to resolve issues involving race was to perform at a very high level. They were very careful. They had dress codes. Except for a few photos that I have of him, almost always when you see Wilkins, he had a shirt and tie on. You had to be able to speak well. If you are a scientist or a mathematician, you had to be top. You had to be a top. You had to be a top person. You just couldn’t go out and say anything you wanted, because it was not so much that you were representing the race, you were representing yourself, and you had high standards.

You have to understand that for people of his status, and I’m talking about in the context of the black community, you did not complain. What you did is if you had issues, you resolved them. They may not be resolved to your satisfaction, but you resolved them.

You see now why a lot of people like J. Ernest and people of his generation, they were very proudly black, even though they didn’t have to do that. Because they felt as if “It is demeaning to deny my ancestors.” They strove to do the best that they could to outperform people.

Narrator: Dr. Percy Julian overcame a lifetime of discrimination to become one of America’s leading scientists. Born in 1899, the grandson of enslaved people, he grew up in Montgomery, Alabama, but was barred from the segregated high school. Nonetheless, he received a PhD in chemistry and was very successful as an entrepreneur. In 1950, he and his family became the first African Americans to move into the exclusive Chicago suburb of Oak Park. But before they even could move in, their house was fire-bombed and later attacked with dynamite. Hundreds of Oak Park citizens were appalled and urged them to stay, but the threats continued. Ronald Mickens shares his amazement at Julian’s determination.

Ronald Mickens: My interest has always been “How within the context of one’s individual environment, how do you, how do you decide that you want to be creative? How do you decide that you’re going to perform at a very high level, and still deal with these other problems?”

How did someone like a Percy Julian function, who was operating at the highest levels of research and development in organic chemistry, and yet had to worry about whether somebody was going to blow up his house, and set his house on fire, or shoot him?

Narrator: At the same time he battled discrimination, Dr. Julian made important discoveries dealing with synthetic hormones, steroids, and other drugs. He became the second African American to be inducted into the National Academy of Sciences.

Manhattan Project laboratories in Chicago and New York were integrated, but black scientists were continuously denied opportunities for advancement. George Warren Reed watched as white scientists accrued benefits from the Army while his own draft board denied his enlistment.

Narrator: Working on the Manhattan Project at Columbia University, African American scientist George Warren Reed noticed that white scientists were being drafted into the Army. Under the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, also known as the “G.I. Bill,” World War II veterans became eligible for low-cost mortgages, low-interest loans, and tuition for higher education. Reed remembers when he tried to enlist.

George Warren Reed: Well, I—before this, had been concerned by the fact that the white guys who were in the group that I was working in were being taken into the Army, kept for six weeks–basic–and then being sent back as PFCs [Private First Class] and corporals. They were then basically Army people.

I went to my draft board in Washington and said, “Look, these people are going in like this. I think I should go in this way too, and I’m 1-A.”

My draft board looked into it and got in touch with me and said, “Look, we’re not allowed to touch you.”

I said, “But these guys are going to go in and when the war is over, they’re going to have all the benefits of having been in the Army, and I’m not going to have anything.”

They said, “We are not allowed to touch you.”

Narrator: During World War II, the US military was segregated, and recruiters routinely turned African Americans away. After the war, white Veterans Administration officials at the state and local level systematically denied loans, mortgages, tuition and other G.I. Bill benefits to black applicants. To pay for his doctorate, George Warren Reed earned the prestigious Julius Rosenwald Fellowship, an award given to African American researchers and intellectuals between 1928 and 1946.

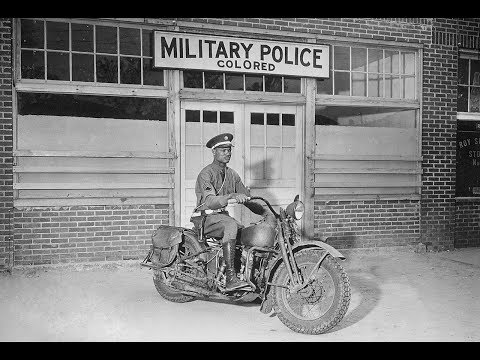

Much like the rest of the Jim Crow South, Oak Ridge had fully segregated facilities until the Supreme Court’s 1954 verdict in Brown vs. Board of Education. During the 1940s, African American workers at Oak Ridge endured injustices for the chance at building a better future.

Narrator: As white Manhattan Project scientists relocated from Chicago to Oak Ridge, African American physicists like J. Ernest Wilkins and George Warren Reed either declined to move or were left behind. Physicist Ronald Mickens describes why J. Ernest Wilkins refused to live in Oak Ridge under Jim Crow.

Ronald Mickens: But he [Wilkins] did talk about the fact that he would not go to any place that would put restrictions on where he lived, who he lived with, and the kinds of amenities that he had grown accustomed to in places like Chicago.

There was no possibility that he would ever go to Oak Ridge under the conditions in which blacks had to live. If you look at most of the other black scientists of that time, almost all of them were in northern cities. There was a lot of discrimination stuff there, too, but they were at Columbia, or they were in Chicago.

Narrator: Reed transferred to Chicago after Jim Crow laws kept him from following his research to Oak Ridge, Tennessee.

George Warren Reed: I had an opportunity to come to Chicago because this place they were talking about–which was in Tennessee–simply wasn’t ready to take on black scientists.

I went to the personnel director in New York and said, “Look, there’s something wrong with this. Why can’t I go where everybody else is given the opportunity to go?”

“Well, it just can’t work that way.”

Much like the rest of the Jim Crow South, Oak Ridge had fully segregated facilities until the Supreme Court’s 1954 verdict in Brown vs. Board of Education. During the 1940s, African American workers at Oak Ridge endured injustices for the chance at building a better future.

Narrator: At Oak Ridge, Tennessee, Manhattan Project officials adhered to strict segregation laws. Seth Wheatley, a white engineer who moved from northern Indiana to work at Oak Ridge, recounts an incident on the bus while en route to Knoxville, Tennessee.

Seth Wheatley: On the way to Knoxville I happened to get on and sit in the last remaining seat.

And shortly after we started out, the bus driver noted that a black man was not sitting on the back row where he was supposed to be, and he stopped the bus along the side of the road.

And I can still see him getting up and walking back and almost grabbing the guy to make him get back to where he’s supposed to be. And of course I had to get up to let him out so it kind of angered me very much, for my background. And I went back to the back row with him and sat down with him.

Narrator: Valeria Steele Roberson describes how segregation affected daily life.

Valeria Steele Roberson: There were some people who talked about some of the racism that they experienced during that time. There’s a man named Paul White—he is still alive—who talks about going to the bus station and ordering a sandwich or whatever. You pay for it and then you go around to the back and they would stick it out of a pigeonhole, as he called it, to him. They were happy to have more money, more opportunities, but racism was still prevalent here in Oak Ridge.

We are people that endure. And they endured whatever in hopes of a better future for them and their families.

The Army’s plans to construct a separate village for African American families at Oak Ridge were scrapped as housing demands grew. African American workers were relegated to “hutments,” separated by gender. Kattie Strickland and her husband were not allowed to live together.

Narrator: Oak Ridge housing was assigned according to earnings. Since African Americans generally had the lowest-paying jobs, they were relegated to the least desirable housing. Many were housed in “hutments,” temporary 16-by-16-foot square structures. Many married African American workers left their spouses and children behind with grandparents or other relatives when they came to Hanford. Valeria Steele Roberson describes her grandmother Kattie Strickland’s housing at at Oak Ridge.

Valeria Steele Roberson: When she arrived in Oak Ridge, she lived in the hutments, which was a section that was set aside for black women. There were usually four women in the room. There was like a potbelly stove in the middle.

Ladies were separated in “The Pen,” surrounded by barbed wire. They were told it was for their protection, that they were enclosed in that area like that. They called that area “The Pen.” The men lived in another section, not too far away from them.

But their stories are different from a Caucasian’s story, for the mere fact that the women were in the hutment section, which was surrounded by barbed wire. The black men and women, even if they were married, couldn’t stay together. My grandmother talks about trying to sneak in to see my grandfather, and vice versa. She said that some of the FBI men really liked her biscuits, so they would turn their heads sometimes and allow them a little time together.

African Americans working on Manhattan Project sites experienced different levels of segregation and discrimination according to where they were employed and the positions that they held.

Narrator: Between 1943 and 1945, about 15,000 African Americans headed out to Hanford. But first, they arrived in the Tri-Cities of Richland, Pasco, and Kennewick. While most Hanford facilities at Hanford were not formally segregated, there were no integrated barracks, and the surrounding towns had racially restrictive covenants. Jackie Peterson explains.

Jackie Peterson: The Hanford area was a little bit strange in the sense that there was no formal segregation, but there wasn’t a huge black population in the Tri-Cities, so Kennewick, Pasco, Richland. People weren’t really sure what to do with this sudden increase in population of African Americans. So again, it was not codified, but through kind of handshake deals between banks and real estate agents, essentially, African Americans that wanted to stay in that area were forced to live in Pasco, which is on the other side of the Columbia River from Hanford.

A lot of these towns became known as sundown towns, because African Americans were not permitted to be in those towns after the sunset. This was enforced by the Kennewick Police Department, and they would be sitting at the foot of the bridge. If you were an African American and you would try to cross the bridge into Kennewick after sundown, you would be turned back. If they saw an African American person within the City of Kennewick after sundown, police would follow you around and ensure that you left.

I’ve heard of places even within downtown Pasco that would refuse to serve African Americans, would refuse to serve people who actually worked at Hanford. It’s like come on, we’re helping our country, we’re doing our duty and yet here we are, we can’t even get a hot meal in the place that we live. So people like to think that places like Washington State were free of racism or segregation, but people found ways.

Narrator: At first, officials insisted that buses carrying workers from Pasco to the Hanford Site needed be segregated. After pressure from African American workers and the NAACP, DuPont integrated the buses in February 1944.

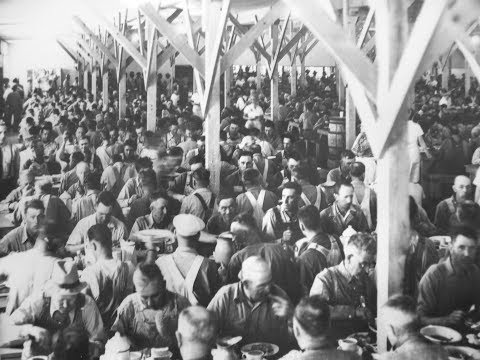

Eating at Hanford was often a hurried affair. The eight mess halls operated 24 hours a day to feed the 50,000 employees. For more information about mess halls at Hanford, watch “10 Minute Meals” in the “Life at Hanford” tour.

Narrator: Hanford’s eight mess halls operated 24 hours a day and were intended to serve all employees. While certain buildings were informally designated for either black or white workers, Luzell Johnson recalls eating in integrated mess halls.

Luzell Johnson: Everybody was working together and everybody was eating together. The white and colored would go in there together and eat.

Narrator: Box lunches were available for employees working off-site for 55 cents. Willie Daniels preferred to make his own lunch.

Willie Daniels: I did not ever buy those box lunches. After I was living in the barracks, I always had me some food in my room, take me a sandwich or something on up. Knew that at noon wasn’t going to be close enough to the barracks. Some of them guys, they ate those box lunches, but I didn’t get any box lunches.

In the Tri-Cities, housing options for African Americans were limited. Racially restrictive covenants and unfair regulations prevented them from purchasing property in Kennewick and Richland until the 1970s. CJ Mitchell and Luzell Johnson were among the workers who lived in Pasco, the only one of the Tri-Cities that allowed African Americans residents.

Narrator: Pasco was the only city that allowed African American residents but only on the east side of the railroad tracks, as Jackie Peterson explains.

Jackie Peterson: There was a small downtown area and kind of the surrounds were populated again by mostly white people. The parts of Pasco that African Americans were relegated to live in were out near the trains and the railyards, which again, very, very underdeveloped, not a lot of facilities or services out that way. So, folks were living in fairly poor conditions.

On the flip side, if you were lucky enough to have made enough money, you could have also purchased a trailer to live on the Hanford campus proper. But again, the trailer setup was such that African Americans were relegated to a very specific area within the trailer camp. Trailers were not cheap, so you really had to have saved your money and been very kind of diligent about putting money away, particularly if you wanted to bring your whole family and have everybody stay together. Staying in a trailer was your best hope.

Narrator: Luzell Johnson recalls buying a trailer when his wife arrived in Hanford.

Luzell Johnson: We went out that Sunday evening, drove around through the trailer camp. We found a trailer for $600 and something dollars. That was just a whole bunch of trailers kind of like trailer camps now. Hanford is just a big town like anything. There are banks and drug stores and everything. We’d go to the store and go back to the trailer. My wife would cook.

Narrator: CJ Mitchell describes the living conditions at Hanford when he arrived as a teenager after the war.

CJ Mitchell: When I first came, everything was segregated at that time. Over in Pasco, while we were living there, there was no running water. There were outdoor facilities, outdoor outhouses. The streets were not paved. You would just go to a spigot and fill up your bucket, or whatever.

We lived over in East Pasco, in a little tent. It was probably maybe eight or nine feet in diameter and it was only, oh, maybe three and a half to four feet high. We actually didn’t sit around in that. That’s where we slept. This tent sat just outside of two small trailers, maybe like eight feet.

My uncle and his wife lived in one side, and my great uncle and his wife lived in the other one.

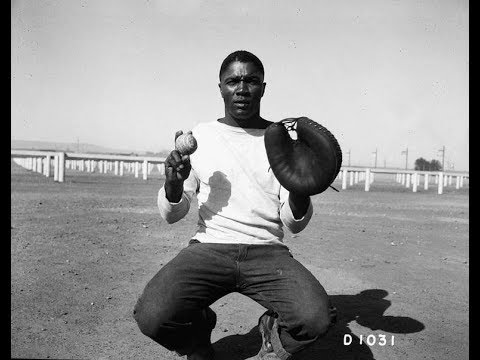

Baseball was an opportunity for different sectors of Hanford to come together.

Narrator: Many Hanford workers spent their rare leisure time playing baseball on Sundays. Willie Daniels, Luzell Johnson, and Roger Fulling remember that the baseball teams were integrated and highly competitive.

Willie Daniels: During the summer, why, they would be playing ball; some of the guys played. They had a ball team out there, played baseball. Of course, I did not ever get on the team, but I would go out and look at them.

Luzell Johnson: Well, it was a mixed league. It was pretty good players from all over the country. When they were working out, the best ones, they would get them. Some big teams would come out and play them.

I played center field for the Hanford team. Not regularly. There were too many of us. We had a good manager, and he would play maybe me this week and then somebody else. The catchers and the pitchers would get a spot—and the first basemen.

Roger Fulling Part 1: Baseball was a great source of relaxation. Each of the crafts had their own team, and there was an organized league between the crafts. One craft in particular was not doing too well, but the head of that craft said he wanted some amends to the baseball standings.

This craft superintendent—unnamed, but known to me—arranged for his recruiters to concentrate on the Pacific Coast League baseball players. As a result, the craft went from the bottom to the top of the league.