Radiation and Safety Monitoring

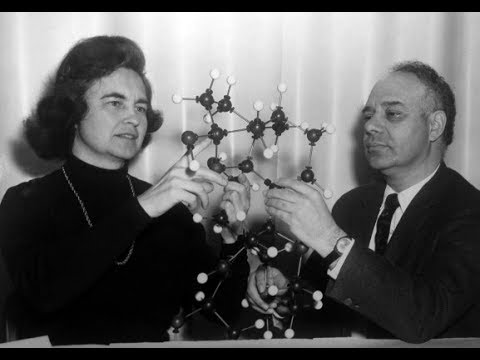

Chemist Isabella Karle describes how her laboratory attempted to safeguard workers against exposure to plutonium.

Narrator: Chemist Isabella Karle worked with the newly discovered element plutonium. The health and safety measures in her laboratory now seem rather primitive, but apparently were effective.

Isabella Karle: As we arrived at the laboratory every morning, we were each handed a dollar-sized – that is, a dollar-coin size – tablet of calcium carbonate flavored with chocolate. The reason for eating this tablet every day to get our calcium was to perhaps change the equilibrium in the body sufficiently so that there would be an excess of calcium, so that plutonium would not lodge itself in our bones.

Our laboratory was a barracks-like building that was built across the street from the University of Chicago football stadium. It was a one-story building. We had powerful fans in the cubicles in which we worked that evacuated the air to the outside. That was considered a safe enough disposal for us. Apparently, it was, because all of us who worked around there have survived to our eighties. I always said maybe a little bit of plutonium is good for you.

Isabella Karle details how a visiting deliveryman accidentally contaminated the Coke machine in her laboratory.

Narrator: Isabella Karle recalls a Coke machine that accidentally became contaminated with a highly radioactive substance, setting off alarms.

Isabella Karle: One day at lunchtime – we all had to go elsewhere to eat lunch. We weren’t supposed to eat anything in the laboratory. I was coming back from lunch a little early and walking down the hallway past the Coke machine and suddenly, my radiation meter went off scale.

What it turned out to be was that while everybody was out to lunch, the deliveryman, who delivered the syrup, couldn’t find his hose and funnel and he didn’t want to go through security again. He looked into the closest laboratory and he saw a length of rubber pipe that would suit him quite well. So he poured the syrup through this rubber hose and left. What he didn’t realize is that he picked up a very radioactive piece of laboratory equipment. The syrup went through it and, of course, contaminated the whole machine.

Fortunately, quite by accident, I was walking by soon enough before anybody had drunk from the machine. By the next day, we had a new Coke machine in which it was impossible to do anything of that sort because the Coke came in bottles.

Physicist James Schoke invented instruments to detect uranium to prevent Manhattan Project workers from taking the dangerous element home with them.

Narrator: James Schoke, a physicist in the instrument group at Chicago Metallurgical Laboratory, was charged with building specialized devices to detect radioactive elements – at first not so much for safety as to catch thieves.

James Schoke: I was told that they were pilfering uranium, which was called “T metal” at the time, from Site B, which was another site on campus where they were machining uranium and cladding it in aluminum for the X-10 reactor at Oak Ridge in order to produce plutonium. I learned all of this only because I was going to work on an instrument to detect uranium because people were walking out with it through the security gate. There was a good reason for that. Uranium was very heavy, very valuable – they were led to believe – by the way it was handled and treated. When it was machined, it gave very large sparks, fiery sparks. And so it was a great souvenir, paperweight.

However, the people working on it did not know it was radioactive. So I was to make an instrument which would detect the chunks of uranium when they were walking out with them to prevent them from taking radioactivity home. And I did develop that, and it was installed and it worked.

James Schoke invented so many new devices during the Manhattan Project that he was assigned a dedicated patent officer.

Narrator: Jim Schoke’s pioneer work on radiation detectors earned him the attention of laboratory director Samuel K. Allison. He also challenged the young physicist with making all sorts of new and innovative devices. Schoke received so many patents during the project that he was assigned a dedicated patent officer to help keep up with his inventions.

James Schoke: Alpha rays are one type of radioactive ray, and I was asked to make improvements in alpha detectors. I worked on that for several months and did make substantial improvements by inventing a new way to use a vacuum tube in the device.

As a result of those inventions, the patent department of the project sent a colonel to file patents on behalf of the project in my name. And he would come looking for me. And everybody would joke about “Schoke’s Colonel” because he would come looking for me. They did file, and it was my understanding the patents were granted, although I never saw them because they belonged to the government.

James Schoke used the skills he learned during the Manhattan Project to start his own nuclear instrument company after the war.

Narrator: After the war, increased demand for radiation detectors led Jim Schoke and several other colleagues from the University of Chicago to launch their own nuclear instrument company. At age twenty-five, Schoke and his company were featured in a 1949 Popular Mechanics article, “The Million-Dollar Baby of the Nuclear Age.”

James Schoke: We hired people who had made Geiger counters on the Project, so they knew how to make them and how to get the apparatus built for making them. Similarly, as our business grew and as we added product lines, we added radioactive chemicals and we hired a radioactive chemist that had been on the project to head up our chemistry and manufacture chemicals with radioactive isotopes that were acquired from the Atomic Energy Commission.

The first thing that I learned on the Manhattan Project was that I had some ability to solve problems with new means. And that was of course paramount in all of the positions and companies that I was involved with.

I would say about two-thirds of the companies that I knew about when I was in the atomic instrument industry were started by people who had been on the Project, or who were coached by somebody who had been on the Project.