Remembering William K. Coors

Brewery magnate Bill Coors directed the Coors Porcelain Company during World War II. He recalls how one day he was contacted by a Manhattan Project official with an urgent request.

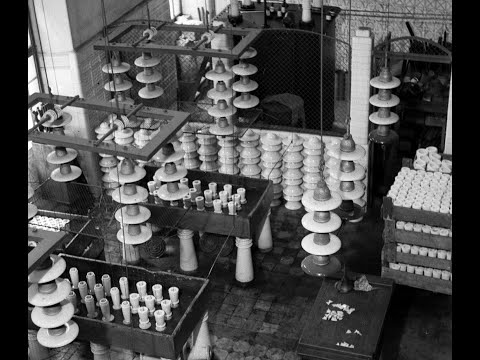

Narrator: As the head of the Coors Porcelain Company during World War II, Bill Coors was contacted by the Manhattan Project when they sought high-quality porcelain insulators for Oak Ridge. He describes the urgency of that mysterious request.

Coors: I didn’t even have a desk or a telephone while I was working. The receptionist at the Coors Porcelain found me at work on an insulator. She said, “There is a phone call for you. They won’t speak to anybody else.”

I followed her into the office, got on the phone. A voice introduced himself as Rick Condit, working for the Lawrence Radiation Laboratory. He said, “We need insulators.”

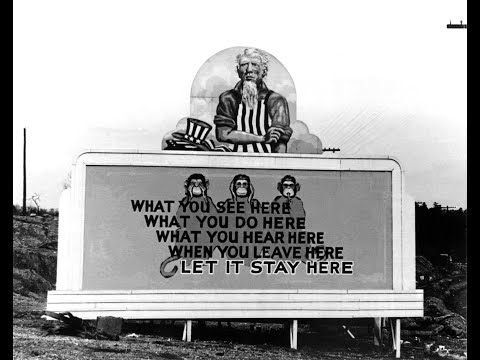

“I’ll send you a drawing. You’re not supposed to copy it, show it to anybody, or talk to anybody about this. It’s a very secret project.”

So, I got a drawing in the mail, and, fortunately, it was an easy item to make.

All the main insulator companies, such as General Electric and Westinghouse, all quoted them in terms of months’ delivery.

I had them on the way in five days.

We had the entire Coors Porcelain facility converted into insulator development, manufacturing. In a matter of fact, just to keep up to date, keep pace with Oak Ridge demand.

I felt success, great success.

Narrator: Coors was not informed what those insulators was used for until many years later.

Coors insulators were instrumental in keeping the Y-12 Plant at Oak Ridge, Tennessee running. As Bill Coors explains, the high voltages used in the plant were causing ordinary insulators to fail and shutting the production process down.

Narrator: The very high voltages used at the Y-12 Plant in Oak Ridge, TN proved too much for normal insulators and that jeopardized production of enriched uranium. Using a secret process and materials acquired from the makers of Champion sparkplug, Bill Coors produced high-quality insulators and did far more quickly than Westinghouse or General Electric.

I did not know at that time that the insulators supplied by General Electric wouldn’t work. Nobody was talking. Nobody said anything.

Porcelain, as made by General Electric and Westinghouse, is very much a slam-bang thing. The main ingredients are kaolin, so porous to get a glassy interior.

You take a regular porcelain insulator, you get it hot enough, and put a heavy enough voltage across it, it will eventually fail.

Then, it dawned on me. Everything was so secret. there were no specifications. They weren’t allowed to keep the blueprint, anything like a blueprints that might identify it.

I’ve had this weird feeling, realization, that that little insulator shop that I was in charge of, making no changes, except my own, was the only facility in the whole western world that could manufacture insulators that could withstand all required of them by the isotope separation.

Narrator: In 2016, the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Legacy Management presented Coors with the Energy Secretary’s Appreciation Award for his contribution to the Manhattan Project.