Scientific Computing

Manhattan Project physicist Julius Tabin on how the differences between the “computers” of World War II and today.

Narrator: Manhattan Project physicist Julius Tabin describes how computers have changed since World War II.

Julius Tabin: Things that are available now, we were just thinking about in those days. Doing some of the calculations for some of the weaponry, they needed mathematics and they needed to do arithmetic very fast. In those days, all we had was a Marchant calculator, and some mechanical calculators with gears and wheels that operated very slowly.

I remember the first computer was in a room several times the size of this room, filled with vacuum tubes, etc., to make simple calculations. Now, if you remember the first early hand computers to do arithmetic, just did addition, division, etc., cost $500 or something for a thing which you can buy for $5 today.

Thom Mason traces how supercomputers have evolved at the national laboratories from the Manhattan Project to today. In 2018, ORNL unveiled Summit, the world’s most powerful supercomputer.

Narrator: Initially developed to help with calculations, Oak Ridge National Laboratory’s early computers were later replace with supercomputers, and those have paved the way for today’s Google, Amazon, and artificial intelligence that have transformed our world. Former Oak Ridge National Laboratory director Thom Mason details the evolution.

Thom Mason: Well, computing has been an important part of the way that the labs have done science since the beginning. So, if you look at the efforts in the Manhattan Project, the supercomputer was Boy Scouts with adding machines. Coming out of the Manhattan Project in the ‘50s, there was a big push for more and more powerful computers, and it was actually the nuclear weapons program that was driving that.

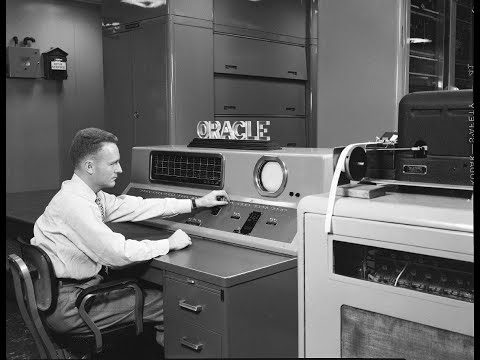

Oak Ridge had a machine called ORACLE [Oak Ridge Automatic Computer Logical Engine] that was sort of the supercomputer of the day. And if you looked at what ORACLE was used for, for example, one of things it was used for was looking at some of those advanced reactor concepts. So, there was a thing called a Homogeneous Solution Reactor that was tested out at Oak Ridge. And, actually, as a consequence of a leak, they had to close off part of the reactor and then they had to calculate “Will it be safe to run this reactor in a way that’s a little bit different than was originally designed for?” They did those calculations on ORACLE.

And, actually, today with our supercomputers, which are vastly more powerful than ORACLE, we do the same sorts of things. We try and numerically integrate formulas that are important. It could be the operations of a nuclear reactor. It could be modeling the climate. It could be trying to understand the dynamics of materials. We do all those things using these massively parallel supercomputers.

And more recently, there’s another piece. It’s now not just the modeling and simulations, but it’s also dealing with huge volumes of data. The ability to use what’s called “machine learning” or “artificial intelligence” to interrogate massive data sets that the human mind could never really get around and extract from that useful information.

When you’re trying to solve really difficult problems, you’ve got to be pretty ingenious to come up with new ways to do them. You know, computers weren’t developed because people thought they wanted to make an Amazon or Google to transform the economy. They were developed because they had to do these calculations. And the adding machines just weren’t cutting it, and so they had to come up with an electronic way to do that in an automated way. Lo and behold, that turned out to have a much wider range of applications than anyone had ever thought.

ORNL nuclear engineer Kevin Clarno explains how the lab uses supercomputers to help ensure the safety of nuclear reactors.

Narrator: Nuclear engineer Kevin Clarno details how supercomputers at Oak Ridge enable engineers to operate nuclear plants more safely and effectively.

Kevin Clarno: We are using the supercomputers to create computer models of how these reactors are operating and what would happen if there were an accident, to understand exactly what’s going to happen. Because we have almost 100 plants in the U.S. that are operating nuclear reactors, providing 20% of the electricity for the country. And they’re operating safely, effectively, efficiently. There is no reason to take any risks with regard to safety. And so, what we’re able to do is we’re able to create computer models that predict what is happening in the plant today and be able to say, “What would happen if tomorrow something failed, some safety system failed? What would happen to the plant?”

Inside of these [reactor] systems, you have very high radiation environments, very high temperatures, coolant flowing. And so, you don’t wind up having a whole lot of sensors and detectors to know exactly what is happening in every single location. There’s no eyes that you’re putting inside of these reactors as they’re operating. And so, through our simulation tools, we’re able to give a clear picture of “This is what is happening at every single location, every single millimeter inside of a plant.” We’re able to give them a perspective of “This is what it looks like and this is what is really happening” to a resolution they’ve never really had before.

So, understanding, in very high detail, what is happening, where is it happening, we can help the plants identify how they can operate the plants. How can they tweak the chemistry in the coolant? How can they adjust the way they’re operating so that they’re operating safer, that they can increase the power they produce without impacting the safety of the plants or the public at all?

With each passing year, supercomputers have developed increasing power and abilities. As Gordon Fee notes, they can even help address seemingly mundane issues such as fuel efficiency on trucks.

Narrator: One surprising way that supercomputers are used is to help produce better skirts for trucks. Former Y-12 plan manager, Gordon Fee, explains.

Gordon Fee: As you go down the road now, watch when you see an 18-wheeler go by you. One of these big trucks. We have thousands of them moving through the city every day. And look under the trailer, and you’ll see on each side a cardboard skirt that hangs between the wheels. And you’ll see today about 40% of the trucks have these skirts underneath them.

They were invented at ORNL, using the supercomputers. Those things only cost about $3,000 a set, one on each side of a trailer.

They were able to model the hydraulics of the wind coming around the cab of a truck and going down the sides or up over the top. And by cutting down the wind patterns under there they decreased the friction and therefore improved the gas mileage.

So, by investing those $3,000, the fuel efficiency is raised somewhere between two and three percent. When you multiply that by the number of trucks on the road, you’re talking about a billion dollars’ worth of savings in fuel. It’s interesting to note, to me, that that had to start with supercomputer to end up with something rather simple.