World War II

Physicist Lew Kowarski explains that before the outbreak of World War II, scientists around the world published research results so other scientists could learn from them. But once the war began, as historian Spencer Weart describes, Leo Szilard expressed concern that sharing research on nuclear chain reactions could help Nazi scientists in their atomic bomb project.

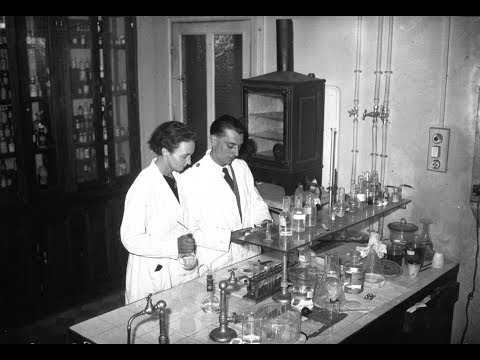

Narrator: Before the war, Frédéric Joliot-Curie’s research contributed to developments by other scientists, and vice versa. Lew Kowarski recalls keeping up with Enrico Fermi’s work through scientific publications. But with the outbreak of World War II in September 1939, scientists stopped sharing their research results. The international race to create an atomic bomb was deadly serious.

Lew Kowarski: The work we did until the outbreak of the war was of definite importance for the work they were doing in America. We simply were working in parallel with Fermi, and we quoted each other. It was a kind of collaboration by publication. We took each other’s results, and so on. That phase ended with the last publication, which was in about September ’39.

After that began the secret phase, in which we influenced very much first the French government and then the British government. The British government did not very much influence the American scientists, but it influenced very much the American government.

Narrator: In the late 1930s, physicist Leo Szilard conducted research on nuclear chain reactions at Columbia University. As Spencer Weart describes, Szilard was very concerned that the French would publish their discoveries and possibly aid Germany’s effort to make an atomic bomb.

Spencer Weart: Then they [Joliot’s team] put the uranium together with the heavy water and they found that yes, you get more neutrons out than you put in. Yes, a chain reaction is possible.

This had also been recognized in Columbia [University], where Leo Szilard was. Szilard wrote to everybody saying, “If you find out that there is a chain reaction, for God’s sake, don’t tell anybody.”

Joliot’s people said, “You are trying to keep us from publishing this. Everybody is going to know it pretty soon anyway.” So, they published the result. At this point, basically, the race for the atomic bomb was on.

Historians Rebecca Erbelding and Spencer Weart explain why the French wanted to keep the heavy water produced at Norway’s Norsk Hydro Plant out of the hands of the Nazis.

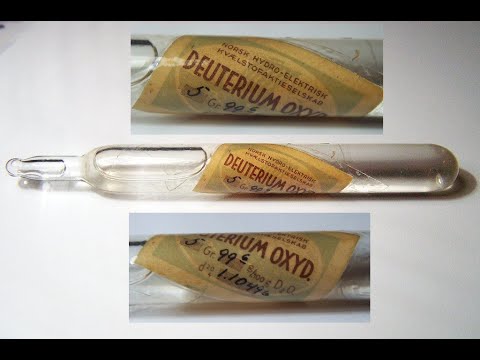

Narrator: For their atomic bomb project, the Germans hoped to use heavy water, or water with a very high density, that in a reactor will moderate or slow down atomic particles and help to produce a nuclear chain reaction. The managers at Norway’s Norsk Hydro Plant were suspicious when German interests suddenly offered to buy all of the operation’s heavy water, as historian Rebecca Erbelding explains.

Rebecca Erbelding: There was a company in Norway that was manufacturing heavy water, but not really in large quantities. In 1939, the company alerted the French government, which was not under Nazi occupation yet, that German companies were trying to buy up their entire supply of heavy water. This sent out alarm bells.

Narrator: Spencer Weart describes how France stepped up to keep Norwegian heavy water out of Nazi hands.

Spencer Weart: They went to a man named Raoul Dautry, who was one of the top bureaucrats, engineer bureaucrats. He later on wound up reforming the French railway system, that kind of a person, in touch with the military in particular. They organized a mission to go to Norsk Hydro clandestinely so that the Germans wouldn’t find out about it or grab it first, and buy their heavy water, and bring it to France, which was kind of a cloak and dagger operation.

Image of Vemork Hydroelectric Plant courtesy of Lynn D. Rosentrater/Flickr.

To prevent France’s supply of heavy water from falling into the hands of the Nazis, Lew Kowarski and Hans Halban left for England on board a ship with the heavy water canisters. Kowarski and Halban’s son Phillippe describe the perilous mission.

Narrator: As the German Army closed in on Paris in June 1940, Lew Kowarski and Hans Halban fled Bordeaux by boat, taking France’s entire supply of heavy water with them. Kowarski recounts their daring escape to England.

Lew Kowarski: We arrived in Bordeaux shortly before midnight. We were led on the boat a few hours after that, that is, the middle of the night. As I like to remind us, staff officers, colonels and possibly the generals, carried our suitcases, because it was at this moment of despair. They had the dim impression that we were carrying some kind of hope.

We very, very definitely, went not as refugees, but as a member of a wartime mission, which was very duly countersigned by all sort of authorities, and that’s how we both considered ourselves all through the war.

Narrator: Phillippe Halban describes his father’s flight from France.

Phillippe Halban: They boarded this coal ship, which looked like a pretty rickety affair. My sister, who was one or two at the time, sat on the canisters of heavy water. They were guided in this enterprise by a flamboyant English earl, the Earl of Suffolk, and they reached England.

It’s funny. At the time, just after my father and Kowarski had left France and arrived in London, Joliot-Curie sent a cable. Obviously he was concerned that people would understand—notably, the Germans—what had been going on. So he said, “H and K have arrived with the gloo-gloo.” “H and K” is “Halban and Kowarski,” and the “gloo-gloo” is, presumably, heavy water.

After the fall of France, Frédéric Joliot-Curie decided to remain in France, while other members of his team, including Lew Kowarski and Hans Halban, left for England and became part of England’s nuclear physics research efforts.

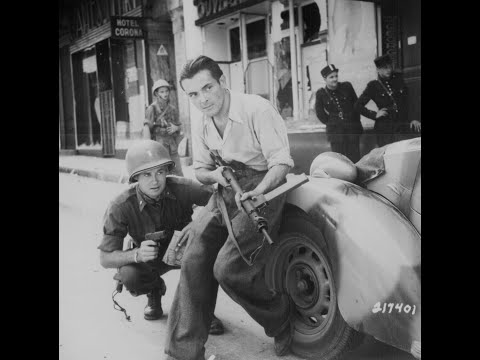

Narrator: In June 1940, the French government surrendered to Nazi Germany. France was divided into a northern German-occupied zone, and a southern zone with a puppet government known as Vichy France. Until German control finally ended with the Allied invasion in 1944, many French citizens resisted the occupation. Historian Garret Martin describes how French General Charles de Gaulle responded to the fall of France.

Garret Martin: Unlike a lot of his other fellow members of government, who advocated an armistice and cooperating with the German invader, de Gaulle really took a very ambitious move to seek refuge in London, and to make a very solemn declaration on the 18th of June 1940 to continue the fight, saying that “France had lost a battle, but they had not lost the war.”

Narrator: Unlike most of his colleagues, Frédéric Joliot-Curie remained in his Paris laboratory throughout the war, as Hélène Langevin-Joliot remembers.

Hélène Langevin-Joliot: My father reached Bordeaux with [Lew] Kowarski, [Hans] Halban, and the papers of the experiment and the heavy water needed for the project of a small atomic reactor, a “pile,” as it was said at that time.

Finally, he decided not to go with Halban and Kowarski, not to go to England, not to leave France, with the idea that the Germans will be defeated at the end. And that you need, during that time, to be able to maintain some science in France, to be able to do it again.

Narrator: Phillippe Halban remembers that his father Hans Halban was inspired by the British resolve to win the war.

Phillippe Halban: Going to England and seeing this admirable resilience, which clearly caught his attention, that he admired, and that, to a certain extent, fascinated him. He was admiring the resilience and, “This is where it’s going to happen. We’re not going to surrender. We are going to win this war.” You couldn’t not but be impressed and overwhelmed by that sort of attitude.

Historians Spencer Weart and Rebecca Erbelding discuss France under Nazi occupation, including Frédéric Joliot-Curie’s role in the French Resistance and France’s collaborationist government.

Narrator: As Spencer Weart describes, Frédéric Joliot-Curie played a significant role in the French Resistance, often at great personal risk.

Spencer Weart: There isn’t any doubt that Joliot gradually became one of the leaders of the Resistance. He was a very prestigious person, so that he was able to command a certain respect among people. The Resistance in France of course was not at first organized at all, and it was underground. Joliot went back to the Collège de France. He set up new scientific work. He got to work on his cyclotron.

But as things progressed and the Resistance became more organized, Joliot began to do Resistance activities. We don’t know much of what they were, but we know that he did help mobilize people. Radios were made for the Resistance in the Collège de France under the Germans’ noses.

They managed to keep their funding and keep people from being deported to work on farms and factories in Germany, which was what happened to young men.

Narrator: Some of the French, especially those with the Vichy government, did not join the Resistance. Instead they collaborated with the German occupiers. As Rebecca Erbelding explains, some Vichy officials even rounded up Jews for the Nazis.

Rebecca Erbelding: France has had a difficult memorial experience, because there are certain segments of the French government that were certainly collaborationist. Vichy France was collaborating. They were turning over foreign Jews. They always met the quota that the Germans asked. The Germans would say, “We need this many thousand Jews to be on a transport to Poland,” and the French government always provided those Jews. The French railroads transported them.

At the same time, there are entire villages that took in Jewish refugees and hid them for the entirety of the war, with intricate systems to alert the entire town when officials were coming in so that people could be hidden properly.