The Y-12 Plant

The Y-12 Plant used an approach to separate isotopes using electrical charges and powerful magnets. Pioneered by Nobel Prize winner Ernest O. Lawrence, the technique is called “electromagnetic separation.”

Narrator: Less than one percent of naturally occurring uranium consists of the isotope U-235. Only this isotope of uranium is “fissile” and suitable for an atomic weapon. Most uranium consists of U-238, a nearly identical but very stable isotope. The challenge was to separate the two isotopes and produce high concentrations of U-235 or enriched uranium.

As Manhattan Project veteran Bill Wilcox explains, project director General Leslie Groves was impressed by Ernest O. Lawrence and the potential of his approach developed at the University of California.

Bill Wilcox: During those first two months, General Groves had the job of going around talking to these university scientists about how this incredibly difficult job of separating uranium-235 from U-238 could possibly be done.

Then he goes to Berkeley, California and he talks to Professor E.O. Lawrence, who is Mr. Enthusiasm. “By gosh, I’m quite sure we can do this using a modification of the cyclotron that I developed.” He explains this to Groves. I’m sure Groves, when he saw this huge, huge cyclotron, these big magnets and these tubes and devices— I’d love to know what he thought.

He [Lawrence] hadn’t separated anything to amount to micrograms of U-235, but was enthusiastic. So at the end of December [1942], Groves made that decision: “We’re going to go with Lawrence’s process, that’s probably the best bet.” And that’s what turned into the Y-12 plant.

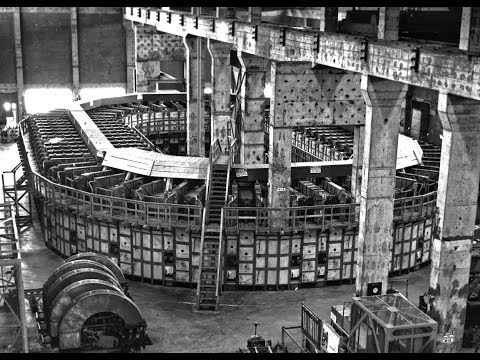

Narrator: Designed at the University of California, the electromagnetic separation plants were called “Calutrons.” “Cal” stood for “California,” “U” for “University,” “Tron” for “cyclotron”: “Cal-U-Tron.”

Bill Wilcox describes how the calutrons at Y-12 separated uranium.

Narrator: Workers constructed more than 1,000 calutrons at Y-12 to separate uranium-235 from uranium-238. Bill Wilcox, who worked at Y-12 during the Manhattan Project, describes how the calutrons worked.

Bill Wilcox: These were complex physics machines, and at Y-12 they ended up with 1,152 of them! 864 were great big ones, about eight feet tall, and the rest of them, 350 or so, were smaller machines.

One of them we call “Alpha calutrons,” one of them we call “Beta calutrons.” The way the separation takes place is that you have an electromagnet, a strong electromagnet, and it’s big, about eight feet tall. And then in between these magnets you put a vacuum tank, pump it out, and you vaporize some uranium tetrachloride.

You heat it up to about 400 degrees, and it boils out of this tank down here at the bottom. Then you bang it with an electron stream and give it a positive charge. You can accelerate that so that the stream comes zipping out. Well, if you didn’t have a magnet, that stream would just go in a straight line until it’s stopped. But with a magnet, it bends that stream in a hemispherical semicircle.

So these charged molecules go zipping around in a long circle, and up at the top, you see, the heavier ones have taken a larger diameter course than the lighter ones.

So up at the top you have a little separation, maybe a quarter of an inch, between the 235 stream and the 238 stream, so then you put a pocket up here with slits in it, and the 238s go in one slit and the 235s in another.

And it’s a batch process—you put so much uranium tetrachloride in here and you run it for three or four days, and then you take it apart and you have to clean everything up and start all over again.

Narrator: The calutrons required an exorbitant amount of energy and 22,000 employees. A year after the war ended, all of the Y-12 calutrons were shut down except for those in Beta 3. These operated until 1998 producing isotopes for medical and other purposes.

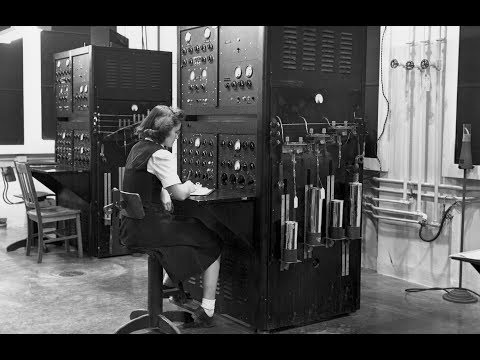

Ted Rockwell and Gladys Evans describe the important roles that young women, known as “calutron girls,” played in the operation of Y-12.

Narrator: Given the wartime shortage of men, young women, often just out of high school, were hired to operate the control panels for the “calutrons.” Ted Rockwell was a member of a special unit that responded to problems at Y-12. He describes how women operated the D-shaped separation units or “calutrons.”

Ted Rockwell: Outside of this area were the control panels, these long panels, one for each of these Ds. And there would be a woman operator there running each of these Ds. They were trained to run this process, a very complicated, tricky process, which at Berkeley had been run only by Ph.Ds. They were not only trained how to do this, but they were trained without telling them what the heck they were doing. They were not told it was uranium. They were merely told that they were making some sort of a catalyst that would be very important in the war.

These women were really incredible. They’d get these things going. And as I said, they had no idea what they were doing really, but they understood how to optimize this mechanism and make it sing.

Narrator: Gladys Evans recalls the challenges of operating the controls to maximize production without “popping off” the machine.

Gladys Evans: You had a board that stood about ten feet tall, a machine-type thing, on this kind of like a board, and it had lots of gauges on it. And you had to turn these gauges constantly. You were trying to raise a needle. The gauge would be about three inches around, and you’d have to try to raise a needle up to get the highest production that you could get.

But you couldn’t take it as high as you wanted to take it or the whole machine would pop off, and then you’d get a blue light, which was a high voltage light. Then that would get you a lot of attention from the foreman and the shift supervisor and everything else. But trying to keep that just below, trying to get as much production as you could out of it, and keep it just below popping off.

You had about, I don’t know, about four or six of these gauges that you were watching. And that was really a tedious thing, to try to keep that production up.