On April 22, 2016, Atomic Heritage Foundation (AHF) staff were privileged to meet with Manhattan Project veteran Ralph Gates at the National World War II Memorial as he participated in a Utah Honor Flight program.

Gates served in the Army as a member of the Special Engineer Detachment at Los Alamos, NM. He was thrilled at the opportunity to come to DC and visit the World War II Memorial and other memorials on the National Mall. His guardian was his friend Craig Sherman, a Vietnam War veteran.

Gates and Sherman flew out from Utah on April 21. Sherman said that when the World War II veterans walked through the airport, people spontaneously stood up and applauded as they passed by. He said witnessing that was incredibly moving.

The Honor Flight events in DC began with a ceremony at the World War II Memorial, which AHF staff attended. The ceremony included a Color Guard, a wreath ceremony, a soldier playing Taps on the bugle, and a group photograph. Afterwards, the veterans were free to tour the memorial.

Several people came up to Gates and thanked him profusely for his service, and asked him where he had served. Gates explained that he had worked on the Manhattan Project, and how challenging the project was. One person remarked that the “Greatest Generation” certainly lived up to its name. Gates modestly responded, “We are not the greatest generation. The greatest generation is the one that is coming up, that will prevent us from getting into the next war.” He also discussed the importance of remembering World War II and the Manhattan Project, and preserving this history for future generations. He was very encouraged by the establishment of the Manhattan Project National Historical Park in 2015.

Several people came up to Gates and thanked him profusely for his service, and asked him where he had served. Gates explained that he had worked on the Manhattan Project, and how challenging the project was. One person remarked that the “Greatest Generation” certainly lived up to its name. Gates modestly responded, “We are not the greatest generation. The greatest generation is the one that is coming up, that will prevent us from getting into the next war.” He also discussed the importance of remembering World War II and the Manhattan Project, and preserving this history for future generations. He was very encouraged by the establishment of the Manhattan Project National Historical Park in 2015.

Later in the day, Gates and his fellow veterans were taken to the FDR Memorial, saw the Drill Team practice at the Navy Memorial, and visited the Iwo Jima Memorial and Arlington National Ceremony, where they attended the changing of the guard. Before flying back to Utah on Saturday, they visited Fort McHenry in Baltimore.

Honor Flights are organized by nonprofits around the country to bring World War II veterans to visit the World War II Memorial in Washington, DC, along with other national memorials. They have 130 “hubs” in 44 states, and flew 20,886 veterans to DC in 2015. Each veteran is accompanied by a “guardian” – a friend or family member who helps the veteran during the trip. While the program was initially focused on World War II veterans, Honor Flights have expanded to bring veterans of the wars in Korea and Vietnam to their respective memorials as well. If you are a Manhattan Project veteran and would like to participate in an Honor Flight, please contact your local Honor Flight program.

For photographs from Gates’s visit and ceremony, please click here or scroll down to the gallery at the bottom of this page.

Ralph Gates and the Manhattan Project

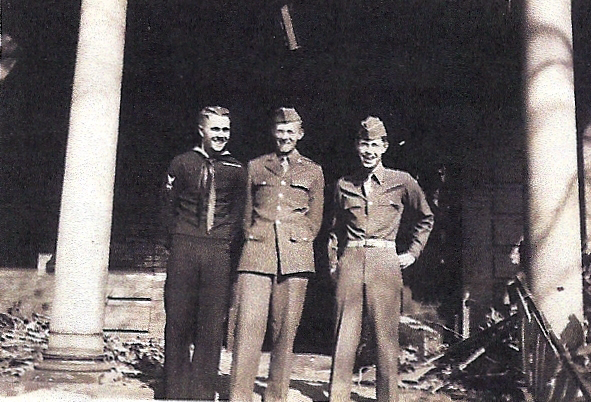

Gates was born and grew up in Nashville, TN. He started college at Vanderbilt University in June 1942 at age 17, studying chemical engineering. He tried to enlist in the Army, but was told to go back to school until the military called him up. In the summer of 1944, he was drafted and went through basic training. In January 1945, instead of being sent to Europe as he had expected, he was selected to join the Special Engineer Detachment (SED). The SED was a group of GIs with scientific and technical backgrounds who contributed to the Manhattan Project.

Nearly 2,000 men were part of the SED in 1945, working at key Manhattan Project sites including Los Alamos, NM, Oak Ridge, TN, Manhattan, and MIT. Most had studied engineering, physics, or chemistry in college before joining the military. Their intelligence and scientific background made them perfect candidates to help with important research and engineering tasks in the Manhattan Project.

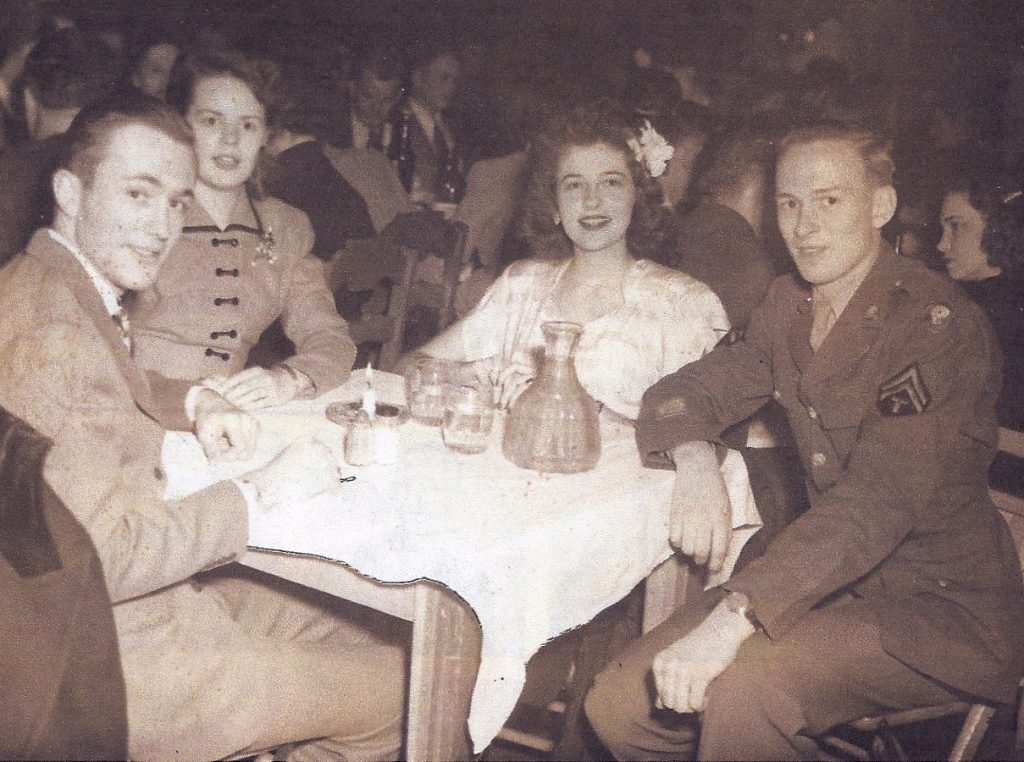

Gates and several other members of the SED were first sent to New York to study engineering at New York University. Gates was in New York for V-E Day. He remembers: “The minute we heard that Germany had surrendered, we cut classes immediately and got on the subway. We beat it down to Times Square in a hurry, where there were a million people in there.

Gates and several other members of the SED were first sent to New York to study engineering at New York University. Gates was in New York for V-E Day. He remembers: “The minute we heard that Germany had surrendered, we cut classes immediately and got on the subway. We beat it down to Times Square in a hurry, where there were a million people in there.

“I remember several things during our stay there that evening: a whole contingent of Free French sailors went marching down the middle of Times Square, singing La Marseillaise. A little guy climbed up on a War Bond sign and he couldn’t get down. Mounted policemen on horseback had to come through and take him off of there. It was a wonderful time. It was a little after dark that my friend, Dick Reed, and I decided that we wanted to go over to Staten Island and back, to see what it looked like that night when the Statue of Liberty was lighted for the first time since the war started. Believe me, the hair is right up on the back of my neck now.”

But the United States was still at war with Japan. Later in May, Gates was sent to Los Alamos. He remembers arriving at the secret town: “We came to a very prominent gate with a big sign up at the top. It said, “The Los Alamos Ranch for Boys.” When I got inside that, being checked in, I didn’t get out until the war was over. That was the first time I’d ever heard of the Los Alamos ranch. It was the next day that I was rushed in at 8:00 to the Tech Area and was given a complete story on what we were there for… I think it was George Kistiakowsky, who was the head of the implosion device, the Fat Man type bomb. He drew this great big circle on a blackboard and said, ‘This is why you’re here. We’re making a new type of bomb.’”

Gates was assigned to work on casting the high explosive shape charges that surrounded the plutonium in the core of the Fat Man bomb, out at S Site in the Tech Area. He went from studying engineering in an academic setting to working with TNT. “Just in case we had trouble, S Site was on a mesa, a little ways out from where the Tech Area was. They built great big berms around us so that if we had an explosion, all the explosion would go up and not do any collateral damage elsewhere…But we never had an accident or any explosion in there.”

He was at work when the news of the bombing of Hiroshima came through: “We heard the news that Harry Truman announced a new bomb had been dropped on Hiroshima. We just exploded with cheering. But we still were at work. We continued casting the implosion type bombs then and we kept that going until Japan surrendered. That’s when we stopped work.”

After the end of the war, Gates completed his engineering degree at Vanderbilt and received a master’s degree in engineering from MIT. He had a successful 40-year career as an engineer in product development and technical sales with Stauffer Chemical Co. Today he lives in Park City, UT, and enjoys telling his Manhattan Project stories to schools and other groups.

For more about Gates and his Manhattan Project experiences, you can watch his interview on AHF’s “Voices of the Manhattan Project” website.

Los Alamos Lament

While Gates enjoyed his time and work at Los Alamos, he and some other members of the SED were disappointed that they were not sent overseas to fight. “We were not totally satisfied with what we had done. When the war in Europe was over, we thought we were going now finally to get into the action in Japan.” He wrote a poem, “Los Alamos Lament,” that gave voice to his conflicted emotions:

“I’m just a PO Box number. I have no real address.

“I’m just a PO Box number. I have no real address.

Although we were selected, I wonder for the best.

We’re not like other people, no one knows what we do.

So, PO Box 180, here’s to you.

They put us on a mountain outside of Santa Fe,

Where the only signs of wildlife are GI bulls at bay.

We’re on a secret mission, and secret work we do.

And when folks ask us what we do, ‘I don’t know, do you?’

And when this war is over, down from this hill we’ll roam.

We’ll ride down from the Shangri-La right to a veteran’s home.

So, heed my words, you children, of brilliance do not boast,

Or you’ll wind up as we have, up in Los Alamos.”