The person that really impresses me most among all the people that I met there was Fermi. He was really an extraordinary man. He happened to be a physicist, but I think he could have gone into any profession, whether by accident or by design, and done extraordinarily well at it. – Crawford Greenewalt

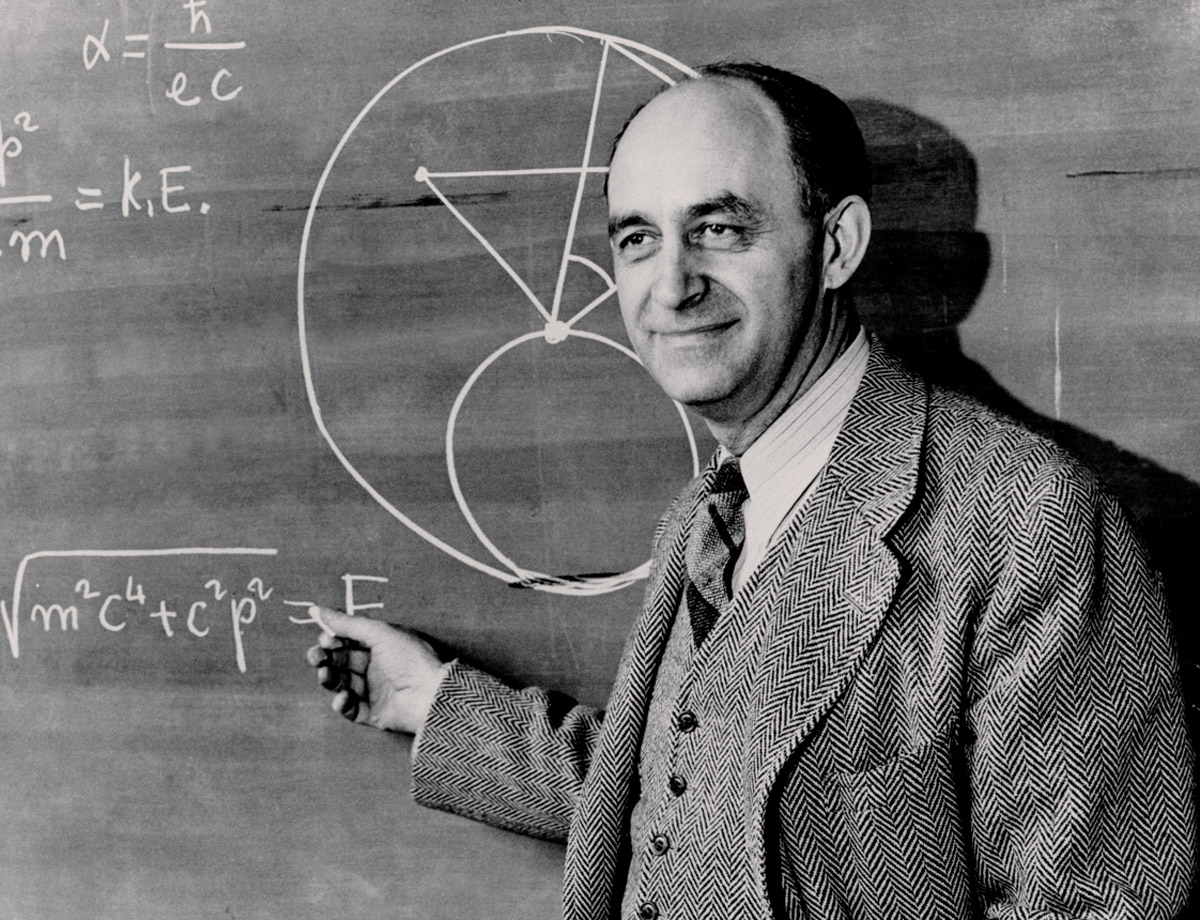

Of all the scientific luminaries who worked on the Manhattan Project, Enrico Fermi was among the most distinguished. He was present at many of the pivotal moments in building the atomic bomb, including the first fission experiment in the United States; the Chicago Pile-1, X-10 Graphite Reactor, and B Reactor going critical; and the Trinity test. A gifted teacher and a master of both theoretical and experimental physics, he was nicknamed “the Pope.”

Recently, collector Ronald K. Smeltzer provided the Atomic Heritage Foundation with a copy of “To Fermi with Love,” a program produced by Argonne National Laboratory in 1971 to give to friends of Fermi and to libraries. You can now listen to the full program – Parts One, Two, Three, and Four – on our Voices of the Manhattan Project website.

The program contains recollections from some of Enrico Fermi’s closest friends and colleagues, as well as remarkable recordings of Fermi himself. In “To Fermi with Love,” we gain not only a fuller appreciation of Fermi’s scientific contributions, but also an understanding of his distinctive traits: honesty, simplicity, and a relentless work ethic.

Early Life

Fermi was born on September 29, 1901 in Rome, Italy. As a boy, a family friend noticed and encouraged his interest in math and science. Fermi proved a brilliant student, winning a scholarship to the Scuola Normale Superiore of Pisa. In 1922, he received his Ph.D. in Physics from the University of Pisa.

Fermi endured several personal tragedies, including the death of his older brother in 1915 and the deaths of his mother and father while still in his twenties. While mourning his mother’s death in 1924, Fermi met Laura Capon, the daughter of an admiral in the Italian Navy. Four years later, he and Laura would marry.

In 1927, Fermi was appointed Professor of Theoretical Physics at the University of Rome. With a group of other young physicists called “Corbino’s Boys,” Fermi and his colleagues made major contributions to the world of physics. In 1926, he discovered the statistical laws (known as Fermi-Dirac statistics) that govern particles subject to Pauli’s exclusion principle.

1934 was a prodigious year for Fermi and his group. They demonstrated that nuclear transformation occurs in almost every element that is bombarded by neutrons, and in May split uranium but did not realize it. In October, Fermi discovered slow neutrons, which in turn contributed to the discovery of nuclear fission. For these breakthroughs, Fermi was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1938.

As Mussolini aligned Italy closer to Nazi Germany, the Fermis’ position became untenable – especially for Laura, who was Jewish. In 1938, Italy enacted the anti-Semitic Racial Laws. “This made an intolerable situation,” Emilio Segrè remembered. “He [Enrico] decided that there was nothing he could do anymore and he had to quit.” The Fermis decided to leave for the United States.

The Manhattan Project

In January of 1939, after accepting his Nobel Prize, Fermi arrived in New York. He accepted an appointment as Professor of Physics at Columbia University. Excited by the discovery of fission, he participated in the first fission experiment in the U.S. within a few weeks of his arrival. “Enrico picked the work up when he heard about the discovery of fission, because fission explained what he had done in Rome and what they had not understood was going on,” Laura explained.

In January of 1939, after accepting his Nobel Prize, Fermi arrived in New York. He accepted an appointment as Professor of Physics at Columbia University. Excited by the discovery of fission, he participated in the first fission experiment in the U.S. within a few weeks of his arrival. “Enrico picked the work up when he heard about the discovery of fission, because fission explained what he had done in Rome and what they had not understood was going on,” Laura explained.

Supported by funding from the U.S. government’s Uranium Committee and its successor, the National Defense Research Committee, Fermi continued to research nuclear chain reactions. Working alongside members of the Columbia University football team, who he recruited to help build chain reacting piles of graphite and uranium, Fermi demonstrated tireless energy.

As the U.S. entered World War II, uranium research took on new urgency. In 1942, Fermi moved to Chicago to work at the University of Chicago Metallurgical Laboratory. Fermi studied the fundamentals of pile operation, building a small experimental unit – the Chicago Pile-1.

On December 2, 1942, CP-1 went critical. It was the world’s first self-sustained, controlled nuclear reaction. Arthur Compton described Fermi’s expression: “There was Fermi’s face—one saw in him no sign of elation. The experiment had worked just as he had expected, and that was that. Cool and collected—Fermi’s face was that of a competent man of action busily engaged on the one important job.”

After the success in Chicago, J. Robert Oppenheimer formally recruited Fermi into the Manhattan Project. In 1944, Fermi became associate director of the laboratory at Los Alamos. At Hanford, he inserted the first uranium fuel slug into the B Reactor. Working with John Wheeler, Fermi helped determine that xenon poisoning was responsible for the mysterious shutdown of the reactor.

After the conclusion of the war, Fermi returned to the University of Chicago, where he became a professor at the Institute for Nuclear Studies. His postwar research focused on pion-nucleon interaction. He also served on the Atomic Energy Commission General Advisory Committee. Fermi died of stomach cancer on November 28, 1954, at the age of 53.

Fermi’s Legacy

Fermi’s Manhattan Project colleagues remembered him as a consummate scientist. “He was a marvelously wise director of scientific effort in the sense that he knew exactly where to be careful, and he could very frequently guess when it was unnecessary to make more accurate measurements. He had a very good sense of the degree of effort that would give the required result without wasting it,” recounted Leona Marshall Libby, a close friend of Fermi’s.

Fermi’s Manhattan Project colleagues remembered him as a consummate scientist. “He was a marvelously wise director of scientific effort in the sense that he knew exactly where to be careful, and he could very frequently guess when it was unnecessary to make more accurate measurements. He had a very good sense of the degree of effort that would give the required result without wasting it,” recounted Leona Marshall Libby, a close friend of Fermi’s.

“Fermi, of course, was outstanding. He just went along his even way, thinking of science and science only,” recalled Manhattan Project leader General Leslie Groves.

“To Fermi with Love” concludes with Fermi’s own words at the ceremony celebrating the tenth anniversary of the operation of Chicago Pile-1. “Scientific thinking and invention flourish best where people are allowed to communicate as much as possible unhampered…Complete secrecy would probably mean complete lack of progress because no fact can be kept a secret better than one that is never discovered.”

Among the many tributes to Fermi’s life and legacy are the Enrico Fermi Award, a prestigious science and technology honor given by the US government. Element 100 is named fermium in his honor.

To learn more about Enrico Fermi’s life and accomplishments, you can listen to the full audio of To Fermi with Love on the “Voices of the Manhattan Project” website. You can also read Fermi’s description of Chicago Pile-1 in the Key Documents section of our website.