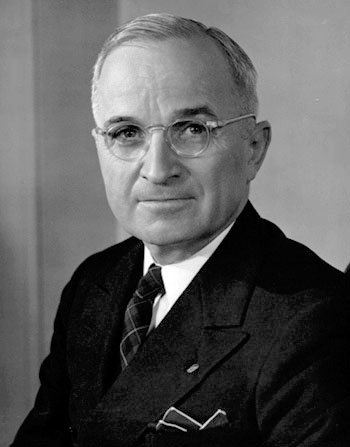

Harry S. Truman (1884-1972) was the 33rd President of the United States of America.

Truman first learned of the Manhattan Project after the death of President Roosevelt in April of 1945, when he relinquished his role as Vice President and took the oath of office as the next president of the United States. Although he knew nothing about the project’s intricacies or nuclear politics in general before Roosevelt’s death, Truman ultimately became in charge of the most difficult moral and tactical decision of World War II: whether or not to drop the atomic bomb. His ultimate decision led to the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

First Encounter with the Manhattan Project

While a Senator from Missouri, Truman took leadership of a committee reviewing defense programs. He began to take note of a troubling fact: the funnelling of millions of dollars into a project simply labeled “Expediting Production,” with no further explanation of what the government was putting this taxpayer money towards. Those in charge of the Manhattan Project had created this ambiguous title to shield the purpose of the top-secret program from public exposure, but the tenacious, devoted, and aggressive Senator Truman felt it was his duty to expose the reason behind this black hole of funding.

Truman went to Secretary of War Henry Stimson in search of answers, but Stimson revealed nothing, informing the senator that the information was classified in order to protect national security. Stimson’s insistence pacified Truman, who gave up the investigation and would not find out about the Manhattan Project until he became president. Truman’s acceptance, despite the senator’s strong sense of duty, demonstrates Stimson’s high reputation in Congress at the time.

Presidential Takeover

The Manhattan Project was kept so secure that not even Truman knew any details of the program until Roosevelt’s death on April 12, 1945. After Truman took the oath of office, both Stimson and advisor (and soon to be Secretary of State) James F. Byrnes finally informed him of the project that Truman had attempted to investigate as a senator just a few years prior. While Byrnes heralded the bomb enthusiastically as the object that would allow the US to dictate its own terms to end the war, Stimson provided the president with a more sobering outlook on the technology, stressing its powerful ability to change international order and that it required a revision of international methods for obtaining peace.

Truman appreciated Stimson’s nuanced position on the bomb, yet overall made clear to Byrnes his approval of the project. The increasing success of the nuclear facilities, meanwhile, sent the program hurtling towards a final completion of the bomb, necessitating a formal decision on whether or not to use the technology.

The Ultimate Decision

While the Interim Committee created by Stimson existed to debate the issue of using an atomic bomb against Japan, the ultimate decision came down to Truman. Upon hearing the Interim Committee’s recommendation on June 1, 1945 to use the bomb as soon as possible against Japan without prior warning, Truman agreed with this decision, saying he could see no other alternative for the war effort. Scientific estimates informed Truman that the first bomb would be ready by August 6, the second around August 24–information that he used in planning when to give Japan a final chance to surrender.

Once his decision to drop the bomb had been made, Truman finally revealed the American creation to Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin at the Potsdam Conference in July of 1945–information that Stalin had already discovered through spy networks. On July 26, as planned, the US, China and Britain released the Potsdam Declaration, demanding Japan’s unconditional surrender, among other conditions.

Japan did not issue a clear response, further solidifying Truman’s decision. Shortly thereafter, U.S. planes dropped two atomic bombs on Japan in a period of three days. On August 6, Little Boy detonated over Hiroshima. On August 9, Fat Man exploded over Nagasaki. On August 14, Japan announced its surrender, and formally surrendered on September 2, ending the war in the Pacific.