In May 1959, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) scouted a remote location in Greenland for Camp Century, so named because it was originally intended to be built 100 miles from the edge of the Greenland ice cap. The USACE selected a site 150 miles from the Thule Air Base in some of the harshest conditions imaginable—temperatures as low as -70°F, winds as high as 125 miles per hour, and an annual snowfall of more than four feet. Despite these challenges, in under two years the Army had constructed a sprawling complex underneath the Arctic ice capable of housing 200 soldiers.

Background

In 1951, the United States and Denmark—both founding members of the North American Treaty Organization (NATO)—signed the Defense of Greenland Agreement. The treaty was intended “to negotiate arrangements under which armed forces of the parties to the North Atlantic Treaty Organization may make use of facilities in Greenland in defense of Greenland and the rest of the North Atlantic Treaty area.” More simply put, the agreement allowed the United States to build military bases in Greenland.

Over the next decade, the American military built three air bases in Greenland: Narssarsuaq, Sondestrom, and Thule. In context of the Cold War, these bases provided a refueling point and a base of operations for intermediate-range strategic bombers. Additionally, the United States deployed radar stations in Greenland to maintain a Ballistic Missile Early Warning System (BMEWS) and a Distant Early Warning (DEW) Line, which would give the United States advance warning of a Soviet nuclear attack. The Thule Air Base is the only of the three which is still operational today; less than 1,000 miles from the North Pole, it is the U.S. Air Force’s northernmost base.

A City Under the Ice

Construction on Camp Century began in June 1959 and was completed by October 1960. Army engineers first had to build a three mile road to bring the 6,000 tons of supplies it would require to build the $8 million facility. Most of the heavy equipment, including vehicles, were brought by bobsleds known as “heavy swings” which had a maximum speed of two miles per hour, making it a 70 hour trip from the Thule Air Base.

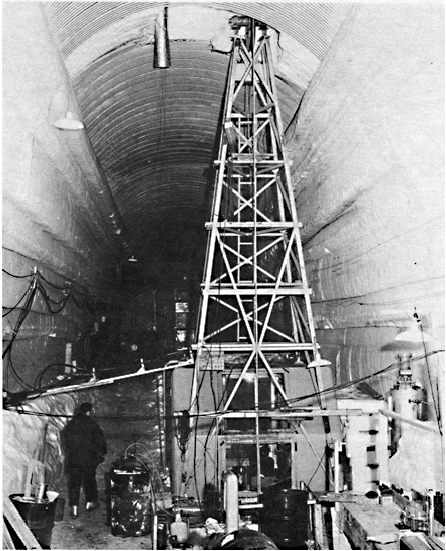

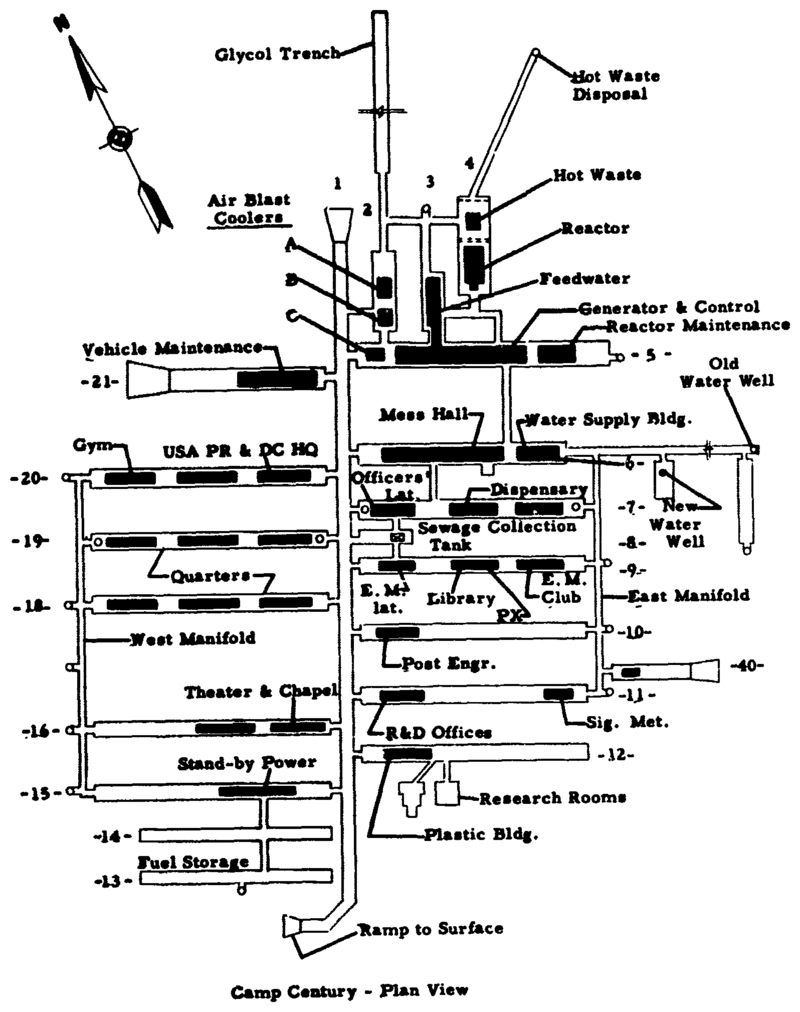

Army engineers first used Swiss-made Peter Plows to dig deep trenches in the snow and ice. The trenches were then covered with a roof of steel arches and topped with more snow. Inside the trenches, engineers set up prefabricated wooden buildings, leaving air space on every side to minimize melting. The largest trench, known as “Main Street,” was more than 1,000 feet long. The engineers drilled a hole deep into the ice, constructing a well which provided 10,000 daily gallons of fresh water. Insulated, heated piping was installed for water and electricity while a series of escape hatches were also built in case of emergency. In the end, Camp Century consisted of 26 tunnels, almost two miles in total. It included dormitories, a kitchen and cafeteria, a hospital, a laundry, a communications center, a recreation hall, a chapel, and even a barbershop.

The last piece of Camp Century was the installment of the PM-2, a portable, medium power nuclear reactor, the first of its kind. This shipment alone consisted of 400 tons of equipment. Everything had to be handled with extreme care; in the subfreezing conditions of Greenland, metal became very brittle and could crack easily. As Major Jim Barnett explained, “We took every precaution in the book, and some that weren’t there, to make sure it would work the first time.” The reactor was successfully installed in 1960. It operated for 33 months before being deactivated and removed.

The camp itself was not a secret. Officially, it was built for scientific purposes under the auspices of the Army Polar Research and Development Center. The Army even produced a short film promoting Camp Century as a “remote research community.” The facility did see some significant scientific discoveries, such as some the first studies of ice cores, revealing geological secrets going back 100,000 years. Science, however was not the primary purpose of Camp Century—the facility was built primarily as a test for a military operation involving nuclear missiles.

Project Iceworm

The scientific developments at Camp Century were a cover for the U.S. Army’s true operation, codenamed “Iceworm,” which sought to deploy ballistic missiles under the Greenland ice. Although the project was eventually canceled and no missiles were ever deployed to Greenland, it would have been an extraordinary engineering and construction achievement had Iceworm come to fruition.

Using the model at Camp Century, Project Iceworm planned to build an additional 52,000 square miles of tunnels—three times the size of Denmark—with the possibility of extending it to 100,000 square miles. The Army planned to deploy 600 missiles, each four miles apart in trenches similar to those at Camp Century, and to build 60 Launch Control Centers (LCCs). Altogether, the project would have required 11,000 soldiers to live full time under the ice. The “Iceman” missile, a modified version of the Minuteman ICBM, was designed as a two-stage rocket with a range of 3,300 miles, giving it the capability to hit most targets in the Soviet Union.

Using the model at Camp Century, Project Iceworm planned to build an additional 52,000 square miles of tunnels—three times the size of Denmark—with the possibility of extending it to 100,000 square miles. The Army planned to deploy 600 missiles, each four miles apart in trenches similar to those at Camp Century, and to build 60 Launch Control Centers (LCCs). Altogether, the project would have required 11,000 soldiers to live full time under the ice. The “Iceman” missile, a modified version of the Minuteman ICBM, was designed as a two-stage rocket with a range of 3,300 miles, giving it the capability to hit most targets in the Soviet Union.

In the early stages of Project Iceworm, getting Danish permission to deploy missiles in Greenland appeared to be a potential roadblock—the 1951 agreement allowing the construction of military bases had said nothing about nuclear missiles. Furthermore, in 1958, Danish Prime Minister H. C. Hansen affirmed, “It must be of importance that we—in our area—refrain from measures, which even unjustly might be construed as provocation and hence impede détente” (Petersen 89). Nevertheless, when U.S. Ambassador Val Petersen approached Hansen to discuss the possibility of Iceworm, the prime minister replied, “You did not submit any concrete plan as to such possible storing, nor did you ask questions as to the attitude of the Danish Government to this item. I do no [sic] think that your remarks give rise to any comments from my side” (90). The U.S. Army interpreted Hansen’s deliberate non-answer as a green light, and went ahead with plans for the project.

The Army advertised Iceworm as an alternative to the Minuteman ICBMs based in the continental United States. Officials cited the “unique adaptability of the Icecap to nuclear deployment,” including its remote location and close proximity to the Soviet Union (79). Iceman missiles stationed at secret locations throughout Greenland would be very difficult to target, ensuring the United States’ second strike capabilities. The Planning Studies Division of the U.S. Army Engineer Studies Center produced its first study of Iceworm in 1960, Strategic Value of the Greenland Ice Cap, in which it concluded,

The missile force is hidden and elusive. It is deployed into an extensive cut‐and‐cover tunnel network in which men and missiles are protected from weather and, to a degree, from enemy attack. The deployment is invulnerable to all but massive attacks and even then most of the force can be launched. Concealment and variability of the deployment pattern are exploited to prevent the enemy from targeting the critical elements of the force (80).

During the early 1960s, American officials also considered Iceworm as a way to share nuclear weapons under the auspices of NATO. At the time, some NATO members, particularly France, wanted to be included in the American-British nuclear sharing program, a controversial request for the United States given its longtime policy of withholding nuclear secrets. Iceworm presented a possible solution to this problem because it would “cement the strategic component of the NATO alliance” (85). The other American proposal for this issue was the creation of a Multi-Lateral Force (MLF), a NATO coalition of ships and submarines that would be armed with the U.S. Navy’s Polaris missile.

In fact, the Navy’s MLF project was one reason why the Army was so interested in Iceworm—Army officials did not want to be left behind in the competition for government funding. The United States ultimately chose the MLF as its official proposal for NATO nuclear sharing. This decision was one of the precipitating factors that led to the cancellation of Iceworm. In the end, however, the MLF did not come to fruition either, as it was summarily rejected by the French government.

Although bureaucratic difficulties certainly contributed, concern over Project Iceworm’s technical feasibility was the primary factor in its demise. For example, Army officials raised concerns over the modifications of the Minuteman required to build the Iceman missile, which would have to operate in extremely cold conditions. Similarly, it would be difficult to locate and communicate with missiles under the Arctic ice. Lastly, and most importantly, it was becoming increasingly clear that the Greenland ice sheet was simply too unstable to support the project. The Army simply could not risk deploying hundreds of missiles in tunnels which could collapse at any moment. As a result, Project Iceworm was officially canceled in 1963.

Legacy

The U.S. Army continued to operate Camp Century in a limited capacity until 1966. Its tunnels quickly collapsed, and today the facility is unreachable, buried under a thick layer of ice. Project Iceworm remained a closely guarded secret until 1997, when the Danish Institute of International Affairs (DUPI) reported Camp Century’s military ambitions.

In recent years, climate change scientists have warned of severe consequences should the Greenland ice sheet melt enough to reveal Camp Century. During its operation, the facility’s nuclear reactor produced over 47,000 gallons of radioactive waste. Although the reactor was removed, this waste remains buried under the ice to this day. As climate scientist William Colgan explained, “They thought it would never be exposed. Back then, in the ‘60s, the term global warming had not even been coined. But the climate is changing, and the question now is whether what’s down there is going to stay down there.” Some scientists have predicted that the Camp Century site will start losing ice by 2090.