The election of President Ronald Reagan in 1980 saw the return of heightened Cold War tensions after a period of détente during the previous decade. The zenith of this escalation arguably came in 1983, when a NATO training exercise almost prompted nuclear war.

Operation RYAN

At a secret meeting of top Soviet officials in May 1981, General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev condemned Reagan, whose aggressive rhetoric was decidedly anti-communist. Yuri Andropov, the head of the KGB and the future General Secretary, furthermore explained that the Reagan administration was preparing for a possible preemptive nuclear strike against the Soviet Union. Andropov announced that the KGB was launching an intelligence program, Operation RYAN, which was an acronym for Raketno-Yadernoe Napadenie, or “nuclear missile attack.”

Operation RYAN primarily relied on Soviet officers stationed abroad to determine if and when an American attack was coming. According to top secret KGB documents from defector Oleg Gordievsky, “The fact that the adversary maintains a considerable part of his strategic forces in a state of operational readiness…makes it essential to discover signs of preparation for RYAN at a very early stage, before the order is given to the troops to use nuclear weapons” (Instructions from the Centre 75). As KGB General Oleg Kalugin recalled, “The slogan” of RYAN was “do not miss the moment when the West is about to launch war.”

Operation RYAN primarily relied on Soviet officers stationed abroad to determine if and when an American attack was coming. According to top secret KGB documents from defector Oleg Gordievsky, “The fact that the adversary maintains a considerable part of his strategic forces in a state of operational readiness…makes it essential to discover signs of preparation for RYAN at a very early stage, before the order is given to the troops to use nuclear weapons” (Instructions from the Centre 75). As KGB General Oleg Kalugin recalled, “The slogan” of RYAN was “do not miss the moment when the West is about to launch war.”

Most of the information on RYAN available to the public today comes from Gordievsky, who was stationed at the Soviet embassy in London at the time. Based on his testimony, it is evident that the operation had flawed principles from its inception. “I quickly discovered that my colleagues in the PR Line regarded RYAN with some skepticism…yet none wanted to lose face and credit at the [KGB] Centre by contradicting the First Chief Directorate’s assessment,” he recalled. “The result was that RYAN created a vicious spiral of intelligence-gathering and evaluation, with foreign stations feeling obliged to report alarming information even if they did not believe it” (Next Stop Execution 261).

The KGB officers in London were ordered to surveil British government officials, determine their routines, and notify Moscow if they were behaving out of the ordinary. The KGB also considered any dramatic change in the number of lights on in buildings at night and the price of blood at donor centers (despite the fact that no one paid for blood in the United Kingdom) to be credible indications of a potential nuclear attack. It can be assumed that Soviet residencies across Europe and in the United States received similar nonsensical instructions. As Gordievsky remembered, “Under [London Station Chief Arkady] Guk’s sometimes alcoholic direction, there were moments when the British end of Operation Ryan more closely resembled the Marx Brothers than Dr. Strangelove” (KGB: The Inside Story 589).

The Powder Keg

With RYAN underway, several developments prior to the Able Archer incident contributed to rising tensions between the two superpowers and greatly increased the Soviet paranoia. The first was Reagan’s famous speech on March 8, 1983 in which he denounced “the aggressive impulses of an evil empire,” declaring the Soviet Union to be “the focus of evil in the modern world.” There was no mincing words; Reagan was calling the Soviet Union the enemy of the United States.

Two weeks later, Reagan announced that his administration was developing the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), dubbed “Star Wars” by the American media. SDI was a complex missile defense system which would theoretically intercept Soviet ICBMs, arguably in violation of the earlier American-Soviet Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty. Although the project never came close to operational use, Soviet officials feared that its success would pave the way for the United States—now freed from the constraints of mutually assured destruction—to launch a nuclear attack on the Soviet Union. Yuri Shvets, a KGB spy at the Soviet embassy in Washington, recalled how the Star Wars program affected Operation RYAN: “As far as the leaders of the KGB intelligence service were concerned, [SDI] jibed beautifully with the RYAN concept, and could not have come at a more opportune time. There was no longer any need to peek into windows, count cars and cut facts out of whole cloth” (Rhodes 158).

The Soviet Union’s fear of a nuclear attack also increased dramatically with the scheduled deployment of NATO Pershing II missiles in West Germany. An American intelligence report later calculated that the missiles’ range of 1800 kilometers would not have reached Moscow, but Soviet officials mistakenly believed that the Pershing II’s 2500 kilometer range “would have been able to strike command and control targets in the Moscow area with little or no warning” (The Soviet “War Scare” 39). KGB documents from 1983 confirmed this belief: “The so-called period of anticipation essential for the Soviet Union to take retaliatory measures…will be considerably curtailed after the deployment of the ‘Pershing-2’ missiles in the FRG, for which the flying time to reach long-range targets in the Soviet Union is calculated at 4-6 minutes” (Instructions from the Centre 76). Reagan did propose a “zero-zero” agreement by which each side would remove its intermediate-range missiles from Europe (the Soviets had 351 SS-20s deployed in Eastern Europe at the time), but the Soviet Union rejected his solution and the Pershing missiles were deployed by the end of 1983.

The Soviet Union’s fear of a nuclear attack also increased dramatically with the scheduled deployment of NATO Pershing II missiles in West Germany. An American intelligence report later calculated that the missiles’ range of 1800 kilometers would not have reached Moscow, but Soviet officials mistakenly believed that the Pershing II’s 2500 kilometer range “would have been able to strike command and control targets in the Moscow area with little or no warning” (The Soviet “War Scare” 39). KGB documents from 1983 confirmed this belief: “The so-called period of anticipation essential for the Soviet Union to take retaliatory measures…will be considerably curtailed after the deployment of the ‘Pershing-2’ missiles in the FRG, for which the flying time to reach long-range targets in the Soviet Union is calculated at 4-6 minutes” (Instructions from the Centre 76). Reagan did propose a “zero-zero” agreement by which each side would remove its intermediate-range missiles from Europe (the Soviets had 351 SS-20s deployed in Eastern Europe at the time), but the Soviet Union rejected his solution and the Pershing missiles were deployed by the end of 1983.

In another incident leading up to Able Archer, the Soviet military shot down Korean Air Lines Flight 007 (KAL007) on September 1, 1983. The Boeing 747, whose radar pattern was similar to the American military Boeing RC-135 spy plane, had flown into Soviet airspace almost 200 miles off course over the Kamchatka Peninsula. After failing to make contact with the pilots, Major Genadi Osipovich shot down the plane, killing all 269 people on board. President Reagan described the incident as a “massacre” and “an act of barbarism born of a society which wantonly disregards individual rights and the value of human life and seeks constantly to expand and dominate other nations.”

Able Archer

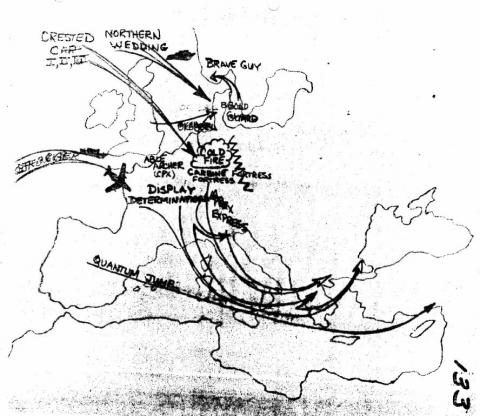

Beginning in the late 1960s, NATO ran annual military exercises in Europe designed to train its forces and test combat readiness. Under the auspices of NATO’s Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe (SHAPE), the exercises typically ran from September to November, and were thus known as Autumn Forge. In the year of the Able Archer war scare, Autumn Forge 83 was made up of six exercises involving approximately 100,000 troops. The largest was Reforger 83 (“REturn of U.S. FORces to GERmany”), in which NATO forces had to defend against the “Orange Pact” (the Warsaw Pact). The Reformer exercise alone involved the airlift of over 16,000 American troops to Europe.

Beginning in the late 1960s, NATO ran annual military exercises in Europe designed to train its forces and test combat readiness. Under the auspices of NATO’s Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe (SHAPE), the exercises typically ran from September to November, and were thus known as Autumn Forge. In the year of the Able Archer war scare, Autumn Forge 83 was made up of six exercises involving approximately 100,000 troops. The largest was Reforger 83 (“REturn of U.S. FORces to GERmany”), in which NATO forces had to defend against the “Orange Pact” (the Warsaw Pact). The Reformer exercise alone involved the airlift of over 16,000 American troops to Europe.

Autumn Forge always culminated with Able Archer, an exercise which tested the command and control procedures for both conventional weapons and weapons of mass destruction. SHAPE historian Gregory Pedlow described Able Archer as follows: “It was an annual Command Post Exercise (thus involving only headquarters, not troops on the ground) of NATO’s Allied Command Europe (ACE), and it was designed to practise command and staff procedures, with particular emphasis on the transition from conventional to non-conventional operations, including the use of nuclear weapons.”

Leading up to Autumn Forge 83, Soviet officials grew paranoid that the West would launch a nuclear attack under the cover of a war game like Able Archer. KGB documents at the time warned about “indirect indications of preparation” such as “announcements of a military alert in units and at bases” and “military exercises” (Instructions from the Centre 87). Fueling this paranoia was the fact that Able Archer 83 differed in several ways from its previous variations. First, the exercise planned for the participation of numerous senior military officials (at one point including Reagan, although he did not end up participating). Second, according to Robert Gates, who was working for the CIA at the time, “The procedures and message formats used in the transition from conventional to nuclear war were different from those used before” (Rhodes 165). Lastly, although no actual troops were used in Able Archer, the exercise moved its imaginary forces to high alert.

Leading up to Autumn Forge 83, Soviet officials grew paranoid that the West would launch a nuclear attack under the cover of a war game like Able Archer. KGB documents at the time warned about “indirect indications of preparation” such as “announcements of a military alert in units and at bases” and “military exercises” (Instructions from the Centre 87). Fueling this paranoia was the fact that Able Archer 83 differed in several ways from its previous variations. First, the exercise planned for the participation of numerous senior military officials (at one point including Reagan, although he did not end up participating). Second, according to Robert Gates, who was working for the CIA at the time, “The procedures and message formats used in the transition from conventional to nuclear war were different from those used before” (Rhodes 165). Lastly, although no actual troops were used in Able Archer, the exercise moved its imaginary forces to high alert.

Able Archer 83 began on November 2, 1983. Within days, KGB agents working on Operation RYAN reported changes in the movement of foreign officers in bases around Europe. On November 8, an emergency telegram was sent to KGB residencies informing them that NATO forces had been placed on high alert. Soviet officials feared that a nuclear attack was imminent. Planes in Poland and East Germany were immediately loaded with bombs, 70 SS-20 intermediate-range ballistic missiles (IRBMs) put on high alert, and nuclear submarines were sent under the Arctic ice, where they would be undetected by American radar and sonar systems. It was not until November 11, the end of Able Archer 83, that Soviet officials ordered their nuclear forces to stand down.

Reaction in the West

United States’ officials at the time were only dimly aware of how seriously the Soviets had reacted to Able Archer 83. An American intelligence report later concluded, “[Able Archer] sounded no alarm bells in the U.S. Indications and Warning system. United States commanders on the scene were not aware of any pronounced superpower tension, and the Soviet activities were not seen in their totality until long after the exercise was over” (The Soviet “War Scare” 8).

The extent of the war scare became much more apparent after Oleg Gordievsky defected in 1985. At the time of Able Archer 83, he was passing information to British intelligence but had not yet left the KGB. Many American officials, however, dismissed the war scare as Soviet propaganda. Gordievsky recalled meeting one senior intelligence officer who believed “that the whole thing had been no more than a deceptive exercise by the Soviet leadership” and “that when Americans observed the actions of Soviet troops inside Russia, and checked signal intensities, there was no hard evidence of anything extraordinary” (Next Stop Execution 377). American officials later admitted that they had “evaluated the Soviet response as unusual but not militarily significant” (The Soviet “War Scare” 8).

Partly thanks to Gordievsky, however, the British intelligence services did believe the Soviet reaction to be genuine. According to recently declassified MI6 documents, Cabinet Secretary Robert Armstrong briefed Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher that the war scare was most likely legitimate since it “took place over a major Soviet holiday, it had the form of actual military activity and alerts, not just war-gaming, and it was limited geographically to the area, central Europe, covered by the Nato exercise which the Soviet Union was monitoring.” Thatcher was so concerned by how close the exercise had come to nuclear war that she ordered British officials to “urgently consider how to approach the Americans on the question of possible Soviet misapprehensions about a surprise Nato attack.”

It was not until 1990 that American intelligence officials acknowledged the shortcomings of their previous analyses of Able Archer. A report by the President’s Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board (PFIAB) concluded that “we may have inadvertently placed our relationship with the Soviet Union on a hair trigger” and “that the US intelligence community did not at the time, and for several years afterwards, attach sufficient weight to the possibility that the war scare was real. As a result, the President was given assessments of Soviet attitudes and actions that understated the risks to the United States” (The Soviet “War Scare” vii). Although the Soviet Union certainly miscalculated the intentions of Able Archer 83, the American intelligence failures described in the 1990 report arguably made the United States equally responsible for the incident.

Legacy

Although less widely known than the Cuban Missile Crisis, the Able Archer 83 war scare was equally dangerous, if not more so. “During the Cuban [Missile Crisis]…both sides were at least aware of the danger and working intensely to resolve the dispute,” explains historian Richard Rhodes. “During Able Archer 83, in contrast, an American renewal of high Cold War rhetoric, aggressive and perilous threat displays, and naïve incredulity were combined with Soviet arms-race and surprise-attack insecurities and heavy-handed war-scare propaganda in a nearly lethal mix” (Rhodes 166).

Many officials who were involved with Able Archer have echoed these sentiments. Paul Dibb, the former director of the Australian Joint Intelligence Organization, recalled, “Able Archer could have triggered the ultimate unintended catastrophe, and with prompt nuclear strike capacities on both the US and Soviet sides, orders of magnitude greater than in 1962.” Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev likewise affirmed, “Never, perhaps, in the postwar decades has the situation in the world been as explosive as in the first half of the eighties” (Rhodes 167).

Beginning in 2013, the United States government declassified a number of documents relating to Able Archer 83, sparking a renewed historical interest in the incident. Able Archer 83 has also appeared in popular culture, such as the 2015 German-American television show Deutschland 83, a fictionalized drama about the war scare.