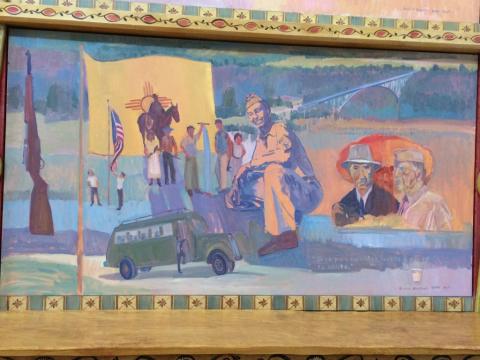

Although frequently omitted from official histories, Hispanos have served in pivotal positions at Los Alamos since its inception. In 1942, the federal government took over the Los Alamos Ranch School for the top-secret Manhattan Project laboratory. Short of laborers, the Army Corps of Engineers soon recruited the neighboring Hispanos to help build the laboratory and residences for what would become known as Los Alamos.

Hispanos and the War Effort

The term “Hispano” refers to people in northern New Mexico of Mexican and Spanish descent. It is different from the term “Hispanic,” which refers to Spanish-speaking communities in all parts of America. The city of Santa Fe and the surrounding area in northern New Mexico have a large Hispano population. Some Hispanos like Frances Quintana can trace their roots to the first Spanish settlers of New Mexico in the 1600s.

In World War II, many Hispano men enlisted in the New Mexican Regiment and helped form the 200th and 515th Coast Artillery regiments. These men were sent to the Philippines because they were Spanish speakers. Tragically, many died as prisoners of war as the Japanese subjected them to the Bataan Death March and other inhumane treatment.

After Los Alamos was chosen for the Manhattan Project’s scientific laboratory, Hispano men and women were recruited to assist with various tasks on “The Hill.” A lack of records makes it difficult to approximate the number of Hispanos who worked at Los Alamos. Yet oral histories and written accounts describe the nature of their work. While most women worked as babysitters and maids, some were technicians and served in other specialized capacities.

Members of the Hispano communities and the Pueblos were recruited as construction workers, janitors, housekeepers and other tasks. However, oral histories of Manhattan Project participants often fail to distinguish between members of the Hispano communities and the Pueblos. For example, few non-Hispanos recognized the differences between Spanish and Pueblo languages like Tewa.

“They would bring them up and they spoke Tewa. I thought we should all learn Tewa because everybody, I thought, spoke Tewa,” Ellen Bradbury Reid, who was a child at Los Alamos, said in an interview with the Atomic Heritage Foundation in 2013. “My mother kept saying ‘Spanish,’ but actually it was Tewa and that was the language we heard.”

Wartime Life at Los Alamos

The project’s green buses stopped at the Hispano communities and the Pueblos in the morning and delivered workers to “the Hill,” as Los Alamos was called. One of the most common jobs for Hispana women was serving as maids for s cientists’ wives. Charlotte Serber originally organized the maid service as an informal volunteer-run effort in May 1943, but as demand rose, the Housing Office took over the operations.

cientists’ wives. Charlotte Serber originally organized the maid service as an informal volunteer-run effort in May 1943, but as demand rose, the Housing Office took over the operations.

Accounts from the wives who used the maid service at times sound paternalistic. Some described the maid service as a curse when unsatisfactory work of their “girls” frustrated them. At the same time, many wives also remembered the maid service as a blessing when they felt overwhelmed with their work. “Our Josephine sometimes amused us, our Juanita pleased us no end, and we worried ourselves over all of them,” Charlotte Serber recalled in her book, Standing By And Making Do.

Oral histories of Hispana women who worked as maids reflect different perspectives. Some appreciated the opportunity to have a paying job and formed close relationships with the families who employed them, often living with them instead of commuting every day.

Frances Quintana worked for David and Frances Hawkins and was particularly fond of their daughter, Julie. “Julie was a lot of fun to take care of. She was the best little girl. I had a lot of brothers and sisters, and she was an angel compared to them,” Quintana remembered in an interview with AHF in 2017. “We used to have a lot of fun. We used to hike, we used to play.”

In addition, the Army, which ran Los Alamos during the Manhattan Project, hired Hispanos to work as gardeners and furnace stokers, as well as waiters and waitresses at Fuller Lodge. Some even served as bodyguards and protected the mail courier who carried confidential mail between Los Alamos and Santa Fe.

“I had a bodyguard, who was a Spanish-American, and spoke very little English,” recalled Adrienne Lowry. “He wore a gun around his waist on a belt and followed me to where I had to go, to the post office and so on. He was protecting me from who knows what. It was amusing, walking with—I think his name was Juan Lujan—walking with Juan in downtown Santa Fe because he had friends that were around in the streets. I remember his making comments to his friends and I could not understand what they were saying.”

Many children of Hispano workers went to school at Los Alamos. Esther Vigil had fond memories of attending school there. “The opportunities we had were far beyond anything that I had seen,” she remembered. “We had activities that went beyond reading, writing, and arithmetic. There was a pond and during the wintertime they would take us ice skating there. [Being in Los Alamos] was an education in itself. It was a tremendous opportunity.”

Many children of Hispano workers went to school at Los Alamos. Esther Vigil had fond memories of attending school there. “The opportunities we had were far beyond anything that I had seen,” she remembered. “We had activities that went beyond reading, writing, and arithmetic. There was a pond and during the wintertime they would take us ice skating there. [Being in Los Alamos] was an education in itself. It was a tremendous opportunity.”

Dolores Heaton, the daughter of a Manhattan Project worker, arrived in Los Alamos in 1945 and found, “All of my area where we lived, the majority of people were Hispanics.” She described going to school with many Hispano classmates. “Secundino Sandoval helped me get through geometry. I was terrible in math, horrible. So, you know, “Would you help me with this?” They were wonderful.”

Many Los Alamos residents also enjoyed the annual Fiesta de Santa Fe festival. The Fiesta included dressing up in costume, dancing, food, and general festivities. Many Los Alamos residents looked forward to this visit to Santa Fe as an opportunity to take a quick respite from the secrecy and isolation of “The Hill.”

Discrimination

In addition to being limited to mostly low-level jobs, Hispanos at Los Alamos also faced overt forms of discrimination.

“Something that a lot of people do not talk about regarding Los Alamos is that we had our fair share of Archie Bunkers up there,” Dimas Chavez remembered. “There were elements of blatant discrimination. I can recall going to birthday parties, not that many but a few, where my cake and ice cream was served to me outside. In later years, there were families whose daughters were not allowed to date Mexican-Americans. Thankfully there was not that much, but it was there.”

Haskell Sheinberg, a member of the Special Engineer Detachment (SED), recalled how certain signs reflected prejudice against Hispanos: “How do you say, ‘Don’t spit on the floor?’ The sign said this in Spanish, never in English, so that you knew that the signs referred to the Hispanic people. It’s like expecting them not to have the same manners or do the things the same way as the non-Hispanics.”

Post War Involvement

After the war, thousands of Manhattan Project participants left Los Alamos to return home. More workers were needed to repair the wartime buildings, which were built as temporary structures and needed to be renovated to be permanent. In 1946, at the urging of Colonel W. A. Stevens and Jack R. Brennand, General Manager of the Robert E. McKee Company, the U.S. government established the Zia Company.

Zia operated the town of Los Alamos for two decades and maintained the technical areas at Los Alamos National Laboratory until 1986. The company provided employment in Los Alamos to many Hispanos. Today, almost 38% of Los Alamos National Laboratory’s employees are Hispanic.

Looking back, some Hispanos view the laboratory as a positive development for the northern Rio Grande communities in the “Valley.” As Lydia Martinez recalled, “[Before] there was not a lot of work. Most people did farming, but once the lab came in, everybody started prospering. You saw everybody improving their homes. There were vehicles and people buying condos here and there. It was a good thing for us living in the Valley.”

Some Hispano Manhattan Project veterans, like Lydia Martinez and Eulalia “Eula” Quintana Newton, continued to work at the laboratory for many years. Martinez worked at the lab for 42 years and earned the Distinguished Performance Award; Quintana Newton worked 53 years and received a Distinguished Service Award. There were even entire families that were employed: sisters, brothers, husband, wife, children, and grandchildren.

Some Hispano Manhattan Project veterans, like Lydia Martinez and Eulalia “Eula” Quintana Newton, continued to work at the laboratory for many years. Martinez worked at the lab for 42 years and earned the Distinguished Performance Award; Quintana Newton worked 53 years and received a Distinguished Service Award. There were even entire families that were employed: sisters, brothers, husband, wife, children, and grandchildren.

In addition to job opportunities, the laboratory built a hospital that provided free services. “Any time you went to the hospital, you did not have to pay a penny, it was free. My uncle had a tonsillectomy there, and since there were no phones in El Rancho when they got back, they were honking—making sure that they knew everything went well. If it had not been for Los Alamos, it would have been hard,” Martinez remembered.

However, not all Hispanos regard the laboratory so positively. Some argue that local communities have become economically dependent on the laboratory and that too few Hispanos have achieved high positions. Anthropologist Joseph Masco details frustrations among local leaders who point to “a chain of institutional forces that made Nuevo-Mexicanos both dependent on LANL and trapped within the lower end of its hierarchy.” The relationship between Los Alamos and its surrounding communities has offered many mutual benefits over the past seven decades, but there are issues that remain to be resolved.

Conclusion

Members of Hispano communities were vital contributors to the Manhattan Project and the continuing operations of the Los Alamos National Laboratory. The Atomic Heritage Foundation looks forward to working with the Hispano community and local partners to publish firsthand accounts by Hispanos remembering the Manhattan Project and reflecting on the intertwined histories of the communities and laboratory over the past seventy-five years.

For oral histories with Hispanos in Los Alamos, see the “Voices of the Manhattan Project” website.