The efforts of the Manhattan Project finally came to fruition in 1945. After three years of research and experimentation, the world’s first nuclear device, the “Gadget,” was successfully detonated in the New Mexico desert. This inaugural test ushered in the nuclear era. Read below for more information about the test, its aftermath, and impacts.

Location

The test was conducted at the Alamogordo Bombing and Gunnery Range, 230 miles south of Los Alamos. The site, located in the Jornada Del Muerto Desert, was chosen for its isolation, flat ground, and lack of windy conditions. Manhattan Project leaders also considered sites elsewhere in New Mexico, as well as in Texas and California.

J. Robert Oppenheimer, Director of the Los Alamos Laboratory during the Manhattan Project, called the site “Trinity.” The Trinity name stuck and became the site’s official code name. It was a reference to a poem by John Donne, a writer cherished by Oppenheimer as well as his former lover Jean Tatlock.

The Gadget

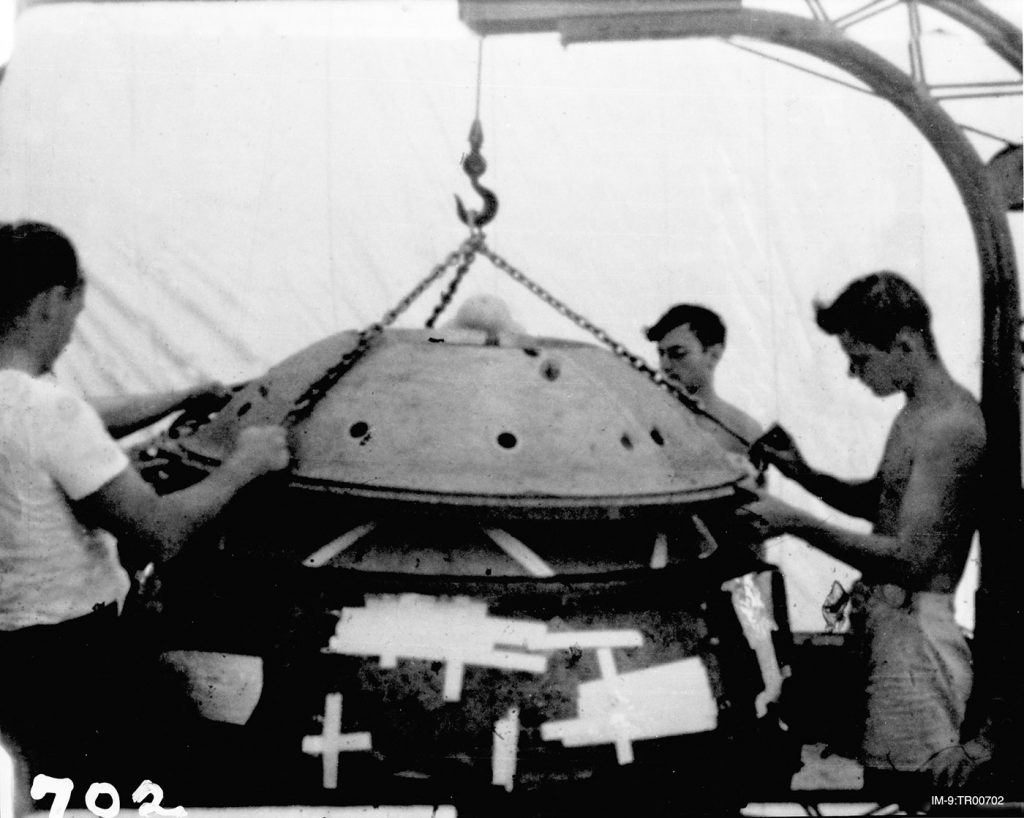

The nuclear device detonated at Trinity, nicknamed “Gadget,” was shaped like a large steel globe. Like the Fat Man bomb dropped on Nagasaki, it was a plutonium implosion device. Plutonium implosion devices are more efficient and powerful than gun-type uranium bombs like the Little Boy bomb detonated over Hiroshima.

Plutonium implosion devices use conventional explosives around a central plutonium mass to quickly squeeze and consolidate the plutonium, increasing the pressure and density of the substance. An increased density allows the plutonium to reach its critical mass, firing neutrons and allowing the fission chain reaction to proceed. To detonate the device, the explosives were ignited, releasing a shock wave that compressed the inner plutonium and led to its explosion.

Jumbo

One unique device that appeared at the Trinity site in the days leading up to the test was Jumbo. Jumbo was a massive cylindrical steel container. Its production was ordered, at a cost of $12 million, by General Leslie Groves as a containment vessel, because of concerns that the test would not be a success. The plan was for the plutonium core to be imploded inside Jumbo. In the event that the Gadget “fizzled,” or did not properly detonate, Jumbo would preserve the bomb’s rare plutonium for future experimentation.

By the time final preparations for the test were underway, however, scientists were confident that the test would work and so Jumbo was not used. Instead, it was suspended from a steel tower 800 meters from ground zero during the test. The tower was destroyed, but Jumbo remained intact. After the war, the Army blew the ends off Jumbo in an unsuccessful attempt to destroy it, and today its remains can be seen at the Trinity Site.

Preparation for the Test

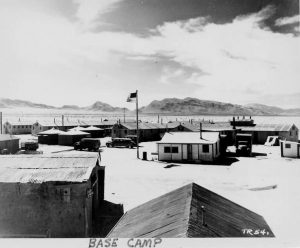

There was a considerable amount of construction that needed to be done in order to prepare the barren desert for its role as a nuclear test site. Kenneth Bainbridge was assigned to lead the test site’s development. In addition to the myriad technical materials required for the Gadget’s successful detonation, a base camp was constructed with ample security measures, albeit Spartan living conditions. Additionally, miles of roads were paved to transport materials to the test site, and multitudes of electrical wires and cables were constructed in order to provide the power that would detonate the gadget during the eventual test.

Much of the preparation for the Trinity test encountered setbacks. The challenges faced in developing the Trinity site were numerous and multifaceted, and there were often close calls that could have jeopardized the outcome of the entire project. Some were almost comical, such as when Kenneth Greisen was pulled over for speeding in Albuquerque while he was driving detonators to Trinity four days before the test. He could have been delayed by several days had the officer checked the contents of his trunk.

A more ominous event was the actual process of winching the Gadget to the top of its tower at the test site. As it was being raised to the top, it came partially unhinged and began to sway. Many observers were stricken with panic at the possibility of the bomb accidentally falling from the tower and detonating, but the Gadget was eventually righted and made its way to the top of the tower without further incident.

Yet Manhattan Project officials were probably most concerned about several failed preliminary tests as they prepared for the actual test. On July 14, just two days before the scheduled date for the Trinity test, Edward Creutz led a dress rehearsal practice test without any nuclear materials. Despite the success of a 100-ton TNT blast in May, Creutz’s test was unsuccessful, and the device failed to detonate.

Fortunately for the scientists concerned by this result, Hans Bethe was able to demonstrate the next day that the test failed because of overworked practice equipment. Since the equipment for the Trinity test was comparatively unused, many scientists were comforted by Bethe’s findings.

Scientists were also frustrated by a test run on the fourteenth by Don Hornig. After spending several months working on the X-5 firing unit that would trigger the bomb’s detonation, Hornig had conducted several tests of his device with no problems. However, his final test failed, provoking many of the same fears as Creutz’s failed experiment. The same issue plagued both tests: the practice materials simply had become worn down after several months of experimentation.

Nevertheless, several scientists participated in an informal pool, betting on how many or how few kilotons of TNT would actually be yielded by the bomb’s explosion. Pessimism swirled around the test site. Unfortunately for the scientists at Trinity, it wasn’t the only thing in the air. A dedicated meteorology team, led by Jack Hubbard, had been stationed at the Trinity site since the end of June. They tracked weather patterns and made critical analyses in order to predict what the weather would be doing on July 16. Their reports called for a storm.

As predicted, wind and rain began to batter the Trinity tower on the night of July 15. Many were worried that the test would be forced to be postponed for several days. Any delay would have been a major psychological strain on a project that had become tremendously stressful for its participants as the project entered its final leg.

External Pressure

Tensions rose at the Trinity site in the weeks leading up to the test. This was no doubt augmented by the events taking place concurrently outside of New Mexico. In Germany, President Harry Truman had delayed his meeting with Soviet and British leaders at the Potsdam Conference until he knew the results from the Trinity test. The success of the Trinity test would have great impact on his strategy for ending the war with Japan. Truman’s voracity to hear the result of the test for diplomatic purposes weighed heavily on the decision makers at Trinity. A failure or delay would draw the ire of the president, and call into question all of the work that had already been done.

At the same time, the United States military had begun naval attacks on the Japanese coast. These were costly, bloody assaults that previewed what might come for the at least the next several months if the atomic bomb proved to be unworkable. As he prepared for the Potsdam Conference, Truman was as attuned to Japan as he was to New Mexico.

The imminence of the Trinity test also caused anxiety within the scientific community. Many were concerned about the new bomb’s deadly potential. The fears ranged in scope, but none were more dramatic than Edward Teller’s stated worry that a nuclear bomb could accidentally ignite the atmosphere, causing global destruction. Teller’s fears of a nuclear apocalypse notwithstanding, the Manhattan Project’s leadership—particularly General Groves—were more concerned with the statement being made by another prominent physicist.

Leo Szilard, a Hungarian-American physicist, had long held strong moral objections to the use of the atomic bomb. It was the reason that, despite his early contributions to nuclear physics and the project, Groves sought to limit his role. Now, with the world on the precipice of its first nuclear detonation, Szilard was disturbed. He did not want to see the weapon used in combat, and so he drafted a petition for President Truman demanding that the Japanese be warned before the atomic bomb was used on them. His petition was signed by dozens of employees at the Chicago Metallurgical Lab and the Oak Ridge project site. The petition never made it to President Truman, and Szilard and several of the petition’s signatories were criticized by Groves and others.

The Test

Many at the Trinity site, despite the hundreds of man-hours spent preparing for this moment, were still unsure that the bomb would detonate the way it was designed to. There were many theoretical variables that no one at the site could be sure how to predict. Many precautions were taken to prepare for all sorts of doomsday scenarios. Soldiers were posted in several nearby towns in the event that they needed to be evacuated. Groves, who was already concerned for the safety of Amarillo, Texas, a city of 70,000 only 300 miles away, placed a call to New Mexico Governor John J. Dempsey explaining that martial law might need to be implemented in the event of an emergency at the site. The Army Public Relations Department prepared somber explanations in the event that disaster occurred and lives were lost.

On July 16, a thunderstorm delayed the test, which was initially scheduled for 4:00 AM. Hubbard’s team determined that the optimal weather conditions would be only be present between 5:00 and 6:00 AM. Groves famously told Hubbard that “I will hang you” if he was incorrect. Luckily for Hubbard, the weather did clear.

The weather seemed to hold, and the scientists and soldiers took their positions for the test a few hours before the rescheduled 5:30 AM detonation. The closest were stationed at shelters 10,000 yards north, west, and south from the tower. These shelters were populated by soldiers and led by Manhattan Project Scientists who were testing for the effects of radiation. The project’s leadership observed the shelter from Compania Hill, about twenty miles from the tower.

At 5:29:45, Gadget detonated with between 15 and 20 kilotons of force, slightly more than the Little Boy bomb dropped on Hiroshima. The Atomic Age had begun.

After years of difficult work, everything finally went according to plan. The test actually yielded more kilotons of TNT than it was predicted to. The complex array of cables, wires, switches, and detonators all worked in unison to create an explosion of energy unlike any the world had ever seen.

Brigadier General Thomas F. Farrell was bewildered by how “the whole country was lighted by a searing light with the intensity many times that of the midday sun. It was golden, purple, violet, gray and blue. It lighted every peak, crevasse and ridge of the nearby mountain range with a clarity and beauty that cannot be described but must be seen to be imagined. It was that beauty the great poets dream about but describe most poorly and inadequately.”

Many others were also invigorated by the test’s success. Greisen observed that “between the appearance of light and the arrival of the sound, there was loud cheering in the group around us. After the noise was over, we all went about congratulating each other and shaking hands. I believe we were all much more shaken up by the shot mentally than physically.”

For photos of the test, please see the gallery below. For rare photographs taken by Marvin Davis, an MP stationed at the Trinity site, click here. For more videos of the Trinity test, visit our YouTube channel. Click here to read more eyewitness accounts of the test.

Aftermath

News of the success of the Trinity test was initially limited to those Manhattan Project scientists who already had knowledge of the atomic bomb, despite the fact that the explosion was felt in cities throughout the state. Officially, the cause was reported as the accidental detonation of a bunker containing a number of high explosives and pyrotechnics. Only after the atomic bombings of Japan was Trinity’s true nature made known.

The explosion annihilated nearly all of the 100-foot metal tower from which the bomb was detonated and created a crater of a radioactive green glassy substance known as trinitite, which is today prized as a collector’s item. Radiation levels at the site remain about 10 times as high as natural background radiation. After being closed to the public for many years, the Trinity Site was declared a National Historic Landmark district in 1965 and was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1966. It is now open to visitors on the first Saturdays of April and October.

Health Impacts on Nearby Communities

The Tularosa Basin Downwinders are individuals from central and southern New Mexico. They mostly reside or resided in Lincoln, Socorro, Otero, and Sierra counties, but can also include others slightly outside of these parameters as well. They are known as “Downwinders” because of their location in relation to the Trinity nuclear test, which was conducted in the arid and sparsely populated Jornada del Muerto desert. The Downwinders claim that they have experienced undue hardships in the years since Trinity because of the test’s radioactive fallout. The negative impacts include increased rates of cancer, other diseases that have caused financial and social stress, and death.

The full impact on the Tularosa Downwinder community is difficult, if not impossible, to gauge. Little was done immediately to assess the health of central New Mexicans, and seventy-plus years have passed since Trinity. However, individuals in the area were almost certainly exposed to dangerously high levels of radiation. Fallout landed on vegetables and animals, food sources that would be consumed by the local population. Eating radioactive materials can lead to various cancers, birth defects, and stillbirths, all issues that Tularosa Downwinders say have plagued their communities. Personal testimony and data seem to affirm these claims. Further, radioactive exposure has been linked to epigenetic changes. When exposed to high doses of radiation, genes can mutate in the person exposed, which is then passed on to successive generations. Oftentimes this causes new diseases, such as heart disease or leukemia, to become passed down hereditarily.

Matters are complicated further by economic and social factors. Access to proper medical care is difficult, oftentimes requiring Downwinders to drive hours to the nearest hospital. A survey conducted in 2017 shows that Lincoln, Socorro, Otero, and Sierra counties face economic challenges, as all four have average household incomes below the state and national average. Many Tularosa Downwinders have been forced to dip into already tight savings accounts to pay for treatments. Some individuals have lost their jobs due to illnesses, while others have pre-existing ailments which limit their job opportunities.

From personal testimony, perhaps the biggest impact on the Tularosa community is generational trauma and mental health. Downwinders describe how different their lives are now that they believe hunting, fishing, and farming may have negative impacts on their physical health. Many feel this changes their identities as individuals, families, and a community. Others feel unacknowledged for the suffering they, and loved ones, have experienced. Financial compensation is important for the Tularosa Downwinders economically, but perhaps more importantly it validates their hardship.

Legal action remains ongoing for the Tularosa Downwinder community. The Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA), passed in 1990 and amended in 2000 and 2002, does not include Trinity Site Downwinders. RECA provides $50,000 to $100,000 in financial compensation for health related expenditures associated with radiation exposure. It covers the Nevada Site Downwinders, certain groups of uranium miners, and workers who participated in atmospheric tests.

The Tularosa Downwinders continue to lobby to become a part of RECA. Recognition under RECA also may ease the qualification for some with pre-existing conditions to get Medicare and Medicaid. After years of litigation, and more than ten years of attempting to get a vote in Congress, a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing on the Downwinders was held on June 27, 2018. Spearheaded by a coalition of Tularosa Downwinders and Navajo leaders, such as Tina Cordova and Jonathan Nez, advocates now await a Senate vote to expand RECA. New Mexico Senator Tom Udall, Idaho Senator Mike Crapo, and New Mexico Representative Ben Ray Luján are among the legislative backers of the Downwinders as they aim for their long-awaited inclusion under RECA.

For more on the Trinity Site Downwinders, see the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium’s 2017 Health Impact Assessment (HIA): “Unknowing, Unwilling, and Uncompensated: The Effects of the Trinity Test on New Mexicans and the Potential Benefits of Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA) Amendments.” Journalist Kelsey D. Atherton also wrote about the Downwinders in a 2017 article in Popular Science. You can visit the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium’s website at www.trinitydownwinders.com.