After the Interim Committee decided to drop the bomb, the Target Committee determined the locations to be hit, and President Truman issued the Potsdam Proclamation as Japan’s final warning, the world soon learned the meaning of “complete and utter destruction.” The first two atomic bombs ever used were dropped on Japan in early August, 1945.

For a detailed timeline of the bombings, please see Hiroshima and Nagasaki Bombing Timeline.

Hiroshima

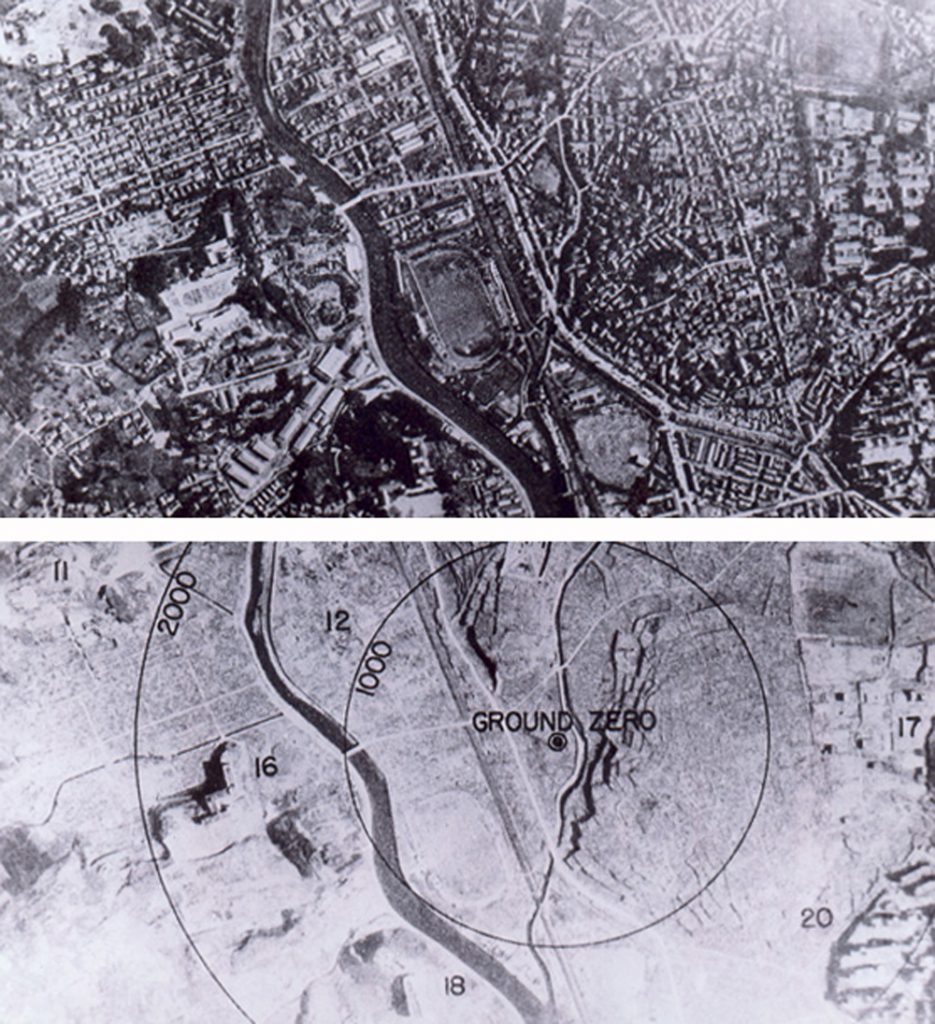

On August 6, 1945, the United States dropped an atomic bomb on the city of Hiroshima. The bomb was known as “Little Boy”, a uranium gun-type bomb that exploded with about thirteen kilotons of force. At the time of the bombing, Hiroshima was home to 280,000-290,000 civilians as well as 43,000 soldiers. Between 90,000 and 166,000 people are believed to have died from the bomb in the four-month period following the explosion. The U.S. Department of Energy has estimated that after five years there were perhaps 200,000 or more fatalities as a result of the bombing, while the city of Hiroshima has estimated that 237,000 people were killed directly or indirectly by the bomb’s effects, including burns, radiation sickness, and cancer.

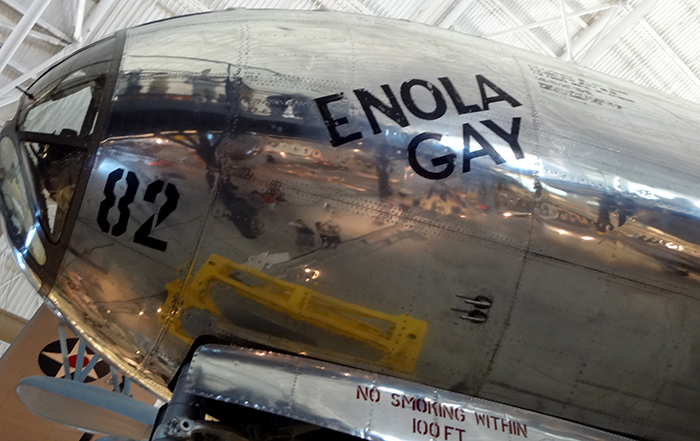

The bombing of Hiroshima, codenamed Operation Centerboard I, was approved by Curtis LeMay on August 4, 1945. The B-29 plane that carried Little Boy from Tinian Island in the western Pacific to Hiroshima was known as the Enola Gay, after pilot Paul Tibbets’ mother. Along with Tibbets, copilot Robert Lewis, bombardier Tom Ferebee, navigator Theodore Van Kirk, and tail gunner Robert Caron were among the others on board the Enola Gay. Below are their eyewitness accounts of the first atomic bomb dropped on Japan.

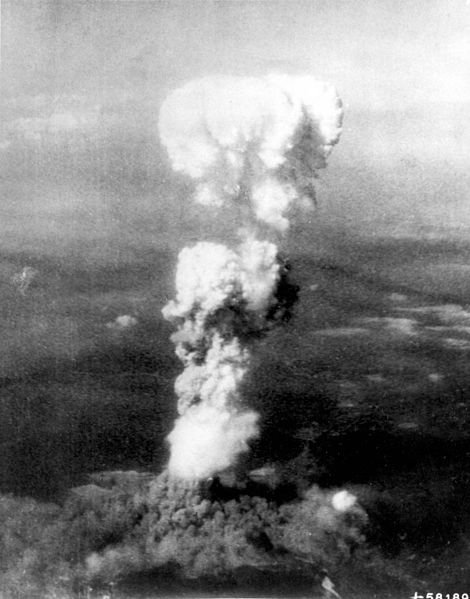

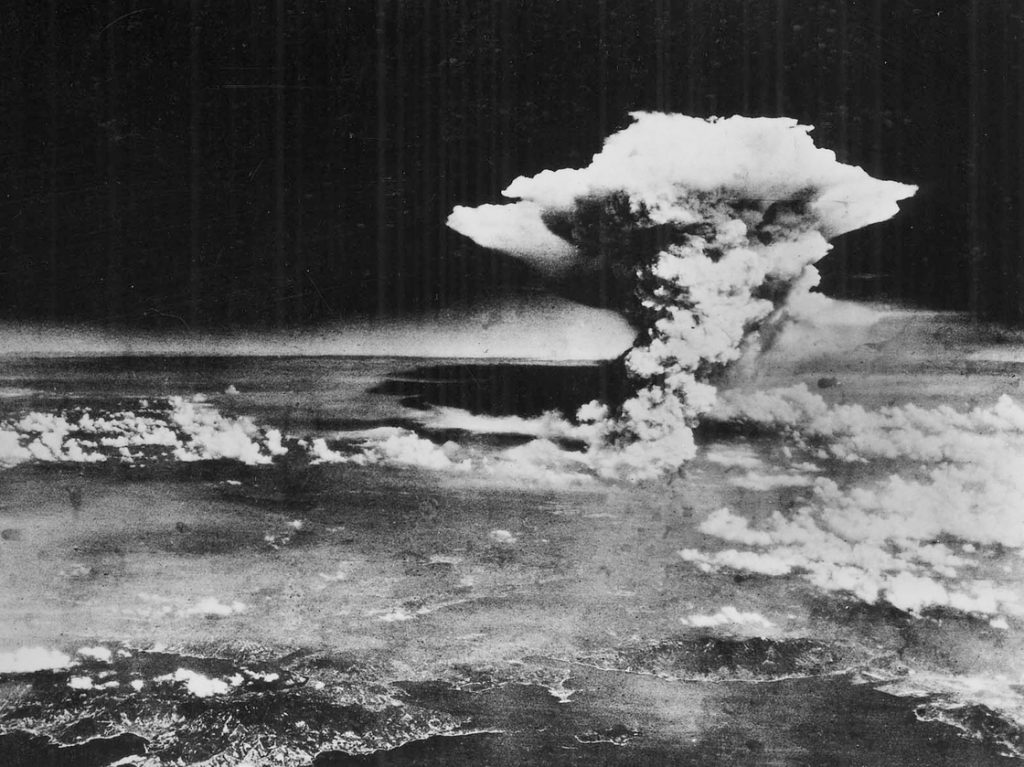

Pilot Paul Tibbets: “We turned back to look at Hiroshima. The city was hidden by that awful cloud… boiling up, mushrooming, terrible and incredibly tall. No one spoke for a moment; then everyone was talking. I remember (copilot Robert) Lewis pounding my shoulder, saying ‘Look at that! Look at that! Look at that!’ (Bombardier) Tom Ferebee wondered about whether radioactivity would make us all sterile. Lewis said he could taste atomic fission. He said it tasted like lead.”

Navigator Theodore Van Kirk recalls the shockwaves from the explosion: “(It was) very much as if you’ve ever sat on an ash can and had somebody hit it with a baseball bat… The plane bounced, it jumped and there was a noise like a piece of sheet metal snapping. Those of us who had flown quite a bit over Europe thought that it was anti-aircraft fire that had exploded very close to the plane.” On viewing the atomic fireball: “I don’t believe anyone ever expected to look at a sight quite like that. Where we had seen a clear city two minutes before, we could now no longer see the city. We could see smoke and fires creeping up the sides of the mountains.”

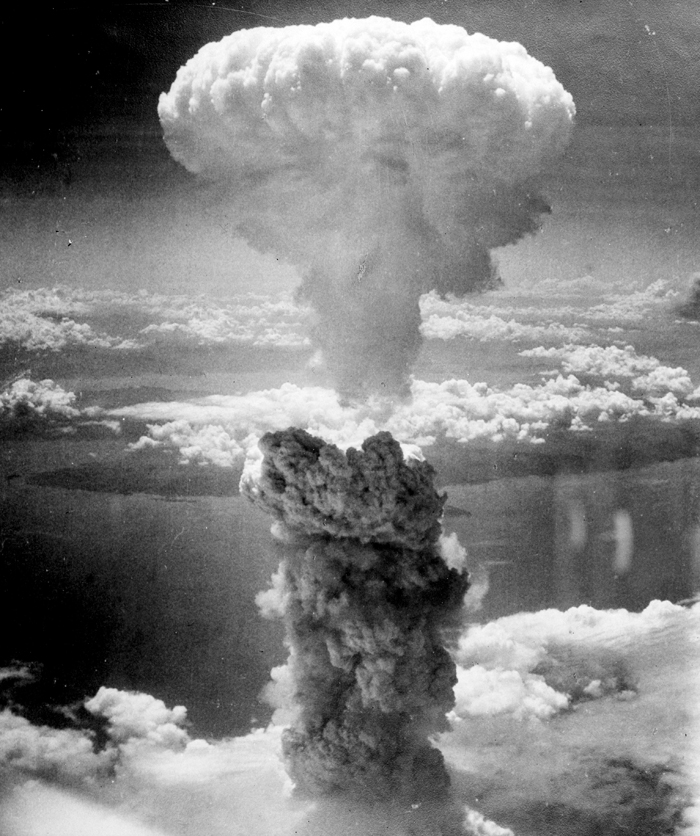

Tail gunner Robert Caron: “The mushroom itself was a spectacular sight, a bubbling mass of purple-gray smoke and you could see it had a red core in it and everything was burning inside. As we got farther away, we could see the base of the mushroom and below we could see what looked like a few-hundred-foot layer of debris and smoke and what have you… I saw fires springing up in different places, like flames shooting up on a bed of coals.”

Six miles below the crew of the Enola Gay, the people of Hiroshima were waking up and preparing for their daily routines. It was 8:16 A.M. Up to that point, the city had been largely spared by the rain of conventional air bombing that had ravaged many other Japanese cities. Rumors abounded as to why this was so, from the fact that many Hiroshima residents had emigrated to the U.S. to the supposed presence of President Truman’s mother in the area. Still, many citizens, including schoolchildren, were recruited to prepare for future bombings by tearing down houses to create fire lanes, and it was at this task that many were laboring or preparing to labor on the morning of August 6. Just an hour before, air raid sirens had sounded as a single B-29, the weather plane for the Little Boy mission, approached Hiroshima. A radio broadcast announced the sighting of the Enola Gay soon after 8 A.M.

The city of Hiroshima was annihilated by the explosion. 70,000 of 76,000 buildings were damaged or destroyed, and 48,000 of those were entirely razed. Survivors recalled the indescribable and incredible experience of seeing that the city had ceased to exist.

A college history professor: “I climbed Hikiyama Hill and looked down. I saw that Hiroshima had disappeared… I was shocked by the sight… What I felt then and still feel now I just can’t explain with words. Of course I saw many dreadful scenes after that—but that experience, looking down and finding nothing left of Hiroshima—was so shocking that I simply can’t express what I felt… Hiroshima didn’t exist—that was mainly what I saw—Hiroshima just didn’t exist.”

Medical doctor Michihiko Hachiya: “Nothing remained except a few buildings of reinforced concrete… For acres and acres the city was like a desert except for scattered piles of brick and roof tile. I had to revise my meaning of the word destruction or choose some other word to describe what I saw. Devastation may be a better word, but really, I know of no word or words to describe the view.”

Writer Yoko Ota: “I reached a bridge and saw that the Hiroshima Castle had been completely leveled to the ground, and my heart shook like a great wave… the grief of stepping over the corpses of history pressed upon my heart.”

Those who were close to the epicenter of the explosion were simply vaporized by the intensity of the heat. One man left only a dark shadow on the steps of a bank as he sat. The mother of Miyoko Osugi, a 13-year-old schoolgirl working on the fire lanes, never found her body, but she did find her geta sandal. The area covered by Miyoko’s foot remained light, while the rest of it was darkened by the blast.

Many others in Hiroshima, farther from the Little Boy epicenter, survived the initial explosion but were severely wounded, including injuries from and burns across much of their body. Among these people, panic and chaos were rampant as they struggled to find food and water, medical assistance, friends and relatives and to flee the firestorms that engulfed many residential areas.

Having no point of reference for the bomb’s absolute devastation, some survivors believed themselves to have been transported to a hellish version of the afterlife. The worlds of the living and the dead seemed to converge.

A Protestant minister: “The feeling I had was that everyone was dead. The whole city was destroyed… I thought this was the end of Hiroshima—of Japan—of humankind… This was God’s judgment on man.”

A six-year-old boy: “Near the bridge there were a whole lot of dead people… Sometimes there were ones who came to us asking for a drink of water. They were bleeding from their faces and from their mouths and they had glass sticking in their bodies. And the bridge itself was burning furiously… The details and the scenes were just like Hell.”

A sociologist: “My immediate thought was that this was like the hell I had always read about… I had never seen anything which resembled it before, but I thought that should there be a hell, this was it—the Buddhist hell, where we were thought that people who could not attain salvation always went… And I imagined that all of these people I was seeing were in the hell I had read about.”

A boy in fifth grade: “I had the feeling that all the human beings on the face of the earth had been killed off, and only the five of us (his family) were left behind in an uncanny world of the dead.”

A grocer: “The appearance of people was… well, they all had skin blackened by burns… They had no hair because their hair was burned, and at a glance you couldn’t tell whether you were looking at them from in front or in back… Many of them died along the road—I can still picture them in my mind—like walking ghosts… They didn’t look like people of this world.”

Many people traveled to central places such as hospitals, parks, and riverbeds in an attempt to find relief from their pain and misery. However, these locations soon became scenes of agony and despair as many injured and dying people arrived and were unable to receive proper care.

A sixth-grade girl: “Bloated corpses were drifting in those seven formerly beautiful rivers; smashing cruelly into bits the childish pleasure of the little girl, the peculiar odor of burning human flesh rose everywhere in the Delta City, which had changed to a waste of scorched earth.”

A fourteen-year-old boy: “Night came and I could hear many voices crying and groaning with pain and begging for water. Someone cried, ‘Damn it! War tortures so many people who are innocent!’ Another said, ‘I hurt! Give me water!’ This person was so burned that we couldn’t tell if it was a man or a woman. The sky was red with flames. It was burning as if scorching heaven.”

For more testimonials from survivors, visit Voices from Japan.

Nagasaki

Three days after the United States dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, a second atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki on August 9 – a 21-kiloton plutonium device known as “Fat Man.” On the day of the bombing, an estimated 263,000 were in Nagasaki, including 240,000 Japanese residents, 9,000 Japanese soldiers, and 400 prisoners of war. Prior to August 9, Nagasaki had been the target of small scale bombing by the United States. Though the damage from these bombings was relatively small, it created considerable concern in Nagasaki and many people were evacuated to rural areas for safety, thus reducing the population in the city at the time of the nuclear attack. It is estimated that between 40,000 and 75,000 people died immediately following the atomic explosion, while another 60,000 people suffered severe injuries. Total deaths by the end of 1945 may have reached 80,000.

The decision to use the second bomb was made on August 7, 1945 on Guam. Its use was calculated to indicate that the United States had an endless supply of the new weapon for use against Japan and that the United States would continue to drop atomic bombs on Japan until the country surrendered unconditionally.

The city of Nagasaki, however, was not the primary target for the second atomic bomb. Instead, officials had selected the city of Kokura, where Japan had one of its largest munitions plants.

The B-29 “Bockscar”, piloted Major Charles Sweeney, was assigned to deliver the “Fat Man” to the city of Kokura on the morning of August 9, 1945. Accompanying Sweeney on the mission were copilots Charles Donald Albury and Fred J. Olivi, weaponeer Frederick Ashworth, and bombadier Kermit Beahan. At 3:49am, “Bockscar” and five other B-29s departed the island of Tinian and headed towards Kokura.

When the plane arrived over the city nearly seven hours later, thick clouds and drifting smoke from fires started by a major firebombing raid on nearby Yawata the previous day covered most of the area over Kokura, obscuring the aiming point. Pilot Charles Sweeney made three bomb runs over the next fifty minutes, but bombardier Beahan was unable to drop the bomb because he could not see the target visually. By the time of the third bomb run, Japanese antiaircraft fire was getting close, and Second Lieutenant Jacob Beser, who was monitoring Japanese communications, reported activity on the Japanese fighter direction radio bands.

Running low on fuel, the crew aboard Bockscar decided to head for the secondary target, Nagasaki. When the B-29 arrived over the city twenty minutes later, the downtown area was also covered by dense clouds. Frederick Ashworth, the plane’s weaponeer proposed bombing Nagasaki using radar. At that moment, a small opening in the clouds at the end of the three-minute bomb run permitted bombardier Kermit Beahan to identify target features.

At 10:58 AM local time, Bockscar visually dropped Fat Man. It exploded 43 seconds later with a blast yield equivalent to 21 kilotons of TNT at an altitude of 1,650 feet, about 1.5 miles northwest of the intended aiming point.

The radius of total destruction from the atomic blast was about one mile, followed by fires across the northern portion of the city to two miles south of where the bomb had been dropped. In contrast to many modern aspects of Hiroshima, almost all of the buildings in Nagasaki were of old-fashioned Japanese construction, consisting of wood or wood-frame buildings with wood walls and tile roofs. Many of the smaller industries and business establishments were also situated in buildings of wood or other materials not designed to withstand explosions. As a result, the atomic explosion over Nagasaki leveled nearly every structure in the blast radius.

The failure to drop Fat Man at the precise bomb aim point caused the atomic blast to be confined to the Urakami Valley. As a consequence, a major portion of the city was protected from the explosion. The Fat Man was dropped over the city’s industrial valley midway between the Mitsubishi Steel and Arms Works in the south and the Mitsubishi-Urakami Ordnance Works in the north. The resulting explosion had a blast yield equivalent to 21 kilotons of TNT, roughly the same as the Trinity blast. Nearly half of the city was completely destroyed.

Bockscar’s copilot Fred J. Olivi published a detailed account of the effects of the atomic explosion over Nagasaki. Here are some of his reactions:

Olivi: “Suddenly, the light of a thousand suns illuminated the cockpit. Even with my dark welder’s goggles, I winced and shut my eyes for a couple of seconds. I guessed we were about seven miles from “ground zero” and headed directly away from the target, yet the light blinded me for an instant. I had never experienced such an intense bluish light, maybe three or four times brighter than the sun shining above us.”

“I’ve never seen anything like it! Biggest explosion I’ve ever seen…This plume of smoke I’m seeing is hard to explain. A great white mass of flame is seething within the white mushroom shaped cloud. It has a pinkish, salmon color. The base is black and is breaking a little way down from the mushroom.”

“The Mushroom cloud was coming right at us. I immediately looked up and could see that he was right, the cloud was getting close to Bockscar. We had been told not to fly through the atomic cloud because it was extremely dangerous to the crew and aircraft. Knowing this, Sweeney put Bockscar into a steep dive to the right, away from the cloud, throttles wide open. For a few moments we could not tell if we were out-running the ominous cloud or if it was gaining on us, but gradually we pulled away from the dangerous radioactive cloud before it engulfed us, much to everyone’s relief.”

Tatsuichiro Akizuki: “All the buildings I could see were on fire… Electricity poles were wrapped in flame like so many pieces of kindling… It seemed as if the earth itself emitted fire and smoke, flames that writhed up and erupted from underground. The sky was dark, the ground was scarlet, and in between hung clouds of yellowish smoke. Three kinds of color—black, yellow, and scarlet—loomed ominously over the people, who ran about like so many ants seeking to escape… It seemed like the end of the world.”

For more testimonials from survivors, visit Voices from Japan.

Aftermath

On August 14, Japan surrendered. Journalist George Weller was the “first into Nagasaki” and described the mysterious “atomic illness” (the onset of radiation sickness) that was killing patients who outwardly appeared to have escaped the bomb’s impact. Controversial at the time and for years later, Weller’s articles were not allowed to be released until 2006.

Controversy

The debate over the bomb – whether there should have been a test demonstration, whether the Nagasaki bomb was necessary, and more – continues to this day.