The Trinity Test

Manhattan Project scientists decided to test the plutonium implosion bomb design in a remote area outside Alamogordo, NM, over 200 miles from Los Alamos.

Narrator: The explosions in the canyons around Los Alamos grew increasingly louder and more powerful in early 1945. For safety’s sake, the first full-scale atomic explosion was planned for the remote deserts of southern New Mexico, about 240 miles away. Author Jennet Conant tells us more.

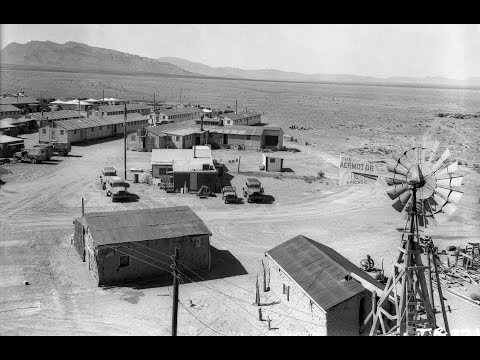

Jennet Conant: When it came time to test this first experimental weapon, they needed a very large amount of acreage and a very remote site. It was a classified weapon. Nobody could know about this test. This was going to be the largest explosion ever conducted by mankind. They had to start looking for a site that was within commuting distance from Los Alamos, because they were going to have to truck the finished weapon, parts, men, and materials. They started hunting around the desert and they found this very remote spot in Alamogordo, just outside Alamogordo, New Mexico. They started building what they call the Trinity Test base camp.

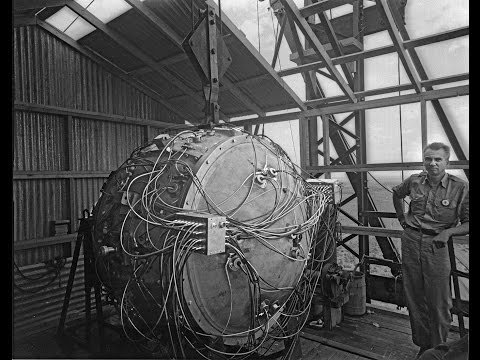

It made Los Alamos look like the Four Seasons. It was really primitive. First, they lived in tents, then in little huts. It was really, really rough. It was all men. They just went in there and hunkered down, and they had to build and complete the weapon there. They then hung it from the steel tower, from which it would be exploded. They built the bunkers and observation buildings where they put all the equipment, very sophisticated equipment, that would measure the force of the explosion and all the different gauges that would do all the different readings for them. The radiation fallout and all of that. Then, bunkers which the scientists could crouch behind for safety.

Looking back, given what we know now, it was horrifyingly close and horrifyingly inadequate protection. Had the wind been blowing the wrong way, they all would have been showered in a fair amount of radioactive dust. But fortune smiled on them that day. Even though it had been a very stormy night and it had looked like they might have to cancel the test, the skies cleared at the last minute and they were able to conduct the test in the pre-dawn hours without incident.

Manhattan Project workers built bunkers around the Trinity Site for witnesses to observe the test, and to hold cameras and instruments that captured key images and information.

Narrator: At the Trinity Site, bunkers were built about five miles away from ground zero. This is where the instruments and cameras were placed, along with eyewitnesses, as Jim Eckles describes.

Jim Eckles: At the site, you get ground zero, and the scientists made the decision that nobody was going to be closer than ten miles outside of a bunker. They built bunkers at 10,000 yards, which was a little over five miles, on the south, west and north basic compass points. People were in those bunkers for the test.

The north and west bunkers were basically camera bunkers, the north one being the prime one for the photos that we see. The motion picture footage and all of those still images of very early stages of the explosion and stuff were taken from the north 10,000-yard bunker.

Narrator: One of J. Robert Oppenheimer’s chief aides was physicist John Manley, who recalls the tiring process of waiting in a shelter for the Trinity Test to begin.

John Manley: I was in charge of one of the three shelters at Trinity. I was at so-called, “West 10,000.” It was a heavily timbered structure with earth piled up over it. I had the responsibility for the people and for the instrumentation in that particular shelter. I remember some of that pretty vividly because the whole thing was such a fatiguing business. From about one o’clock until four or so in the morning, I think that I was the only person awake in the whole shelter. People were just lying on the floor asleep, just dead.

Elsie McMillan remembers asking her husband Edwin what would happen at the Trinity Test.

Narration: J. Robert Oppenheimer decided to test the plutonium bomb or “Gadget” in the desert of the Alamogordo Bombing Range, about 240 miles from Los Alamos. Oppenheimer named the site “Trinity,” inspired by John Donne’s poetry, “Batter my heart, three-person’d God.” Elsie McMillan asked her husband Ed what to expect.

Elsie McMillan: Things were moving fast now. There soon would be a test near Alamogordo at White Sands, the very place we had visited with carefree abandon a few years ago. I asked Ed in all innocence what would happen. It seemed an easy question, with a simple answer. Knowing that it was an atomic bomb they were testing should have made me more aware of what would be involved.

It was difficult for Ed to tell me. He finally answered, “There will be about 50 of us present, key workers. We ourselves are not absolutely certain what will happen. In spite of calculations, we are going into the unknown.

“We know that there are three possibilities. One, that we will all be blown to bits, if it is more powerful than we expect. If this happens, you and the world will be immediately told. Two, it may be a complete dud. If this happens, you will also be told. Third, it may, as we hope, be a success, we pray without loss of any lives. In this case, there will be a broadcast to the world with a plausible explanation for the noise and the tremendous flash of light which will appear in the sky.”

With our alarms set for 2:30 a.m., Ed would leave at 3:15. We did not want to allow much time. We did not want to say goodbye.

Elsie McMillan vividly describes waiting with her neighbor Lois Bradbury for word that the Trinity Test had been a success.

Narrator: Elsie McMillan remembers waiting up all night to see a glimpse of the test with her neighbor Lois Bradbury. Lois’ husband Norris Bradbury was in charge of the final assembly of the “Gadget,” or plutonium test bomb.

Elsie McMillan: There was a light tap on my door. There stood Lois Bradbury, my friend and neighbor. She knew. Her husband was out there, too. She said her children were asleep, and would be all right since she was so close and could check on them every so often.

“Please, can’t we stay together this long night?” she said. We talked of many things, of our men, whom we love so much, of the children, their futures, of the war with all its horrors. We kept the radio going softly, despite the fact our last word had been that the test would probably be at 5:00 a.m. We dared not turn it off.

Suddenly, there was a flash and the whole sky lighted up. The time was 5:32 a.m. The baby didn’t notice. We were too fearful and awed to speak.

The news came. “Flash! The explosive dump at the Alamogordo airfield has exploded. No lives are lost. This explosion is what caused the tremendous sound and the light in the sky.”

We looked at each other. It was a success. Could we believe the announcement, no lives are lost? They had not said no injuries. We had hours to wait to be absolutely sure. At least it was over with.

Lois went home to grab a few hours of rest before her family might awaken. I, too, crawled into bed, but found I could not sleep. The day dragged on. I tried walking the mesa with the children, but by lunchtime home was where I wanted to be.

The door opened about 6:00 o’clock in the evening. We were in each other’s arms. Then, and only then, did the tears come streaming down my face.

Manhattan Project photographer Berlyn Brixner recalls being stunned by the large explosion of the Trinity Test.

Narrator: Manhattan Project photographer Berlyn Brixner remembers the critical moment surrounding the Trinity Test.

Berlyn Brixner: Well, I was sitting at one of my cameras, motion picture cameras, which was on a panoraming device. I was just sitting there with the camera running. Everything was operated from the central control station. So I didn’t have to do anything at the time but just sit there.

I had a loudspeaker actually and was listening to the countdown, and so I knew when the explosion was to occur. I had arranged a very dense welding glass type of glasses in front of my eyes, and I was looking directly at the Zero. I was one of the few people allowed to do that. It was perfectly safe through these welding glasses. I was looking right at it, just staring at where it was.

Of course, it was nighttime. I couldn’t see anything. But when the explosion went off, that welding glass seemed to just glow white, just intense white like the sun. So it just blinded me, and so I looked aside to the left. The Oscura Mountains were at the left, and they were just lit up like daylight then. So I looked at that for a few seconds, and then I looked back through my welding glass and I saw that the terrific explosion had taken place. Just unbelievably large explosion.

My camera was just sitting there, but soon the ball of fire was starting to rise and I thought, “Gee, I better get busy!” So abruptly I raised it, and photographed the ball of fire as it went up to the stratosphere. I kept photographing it for the next couple of minutes or so.

I knew immediately that the explosion had exceeded the greatest expectations and that essentially we had won the war, because that bomb would soon be used on Japan. And it was. That was July the 16th, I believe, and the war was over only about three weeks later.