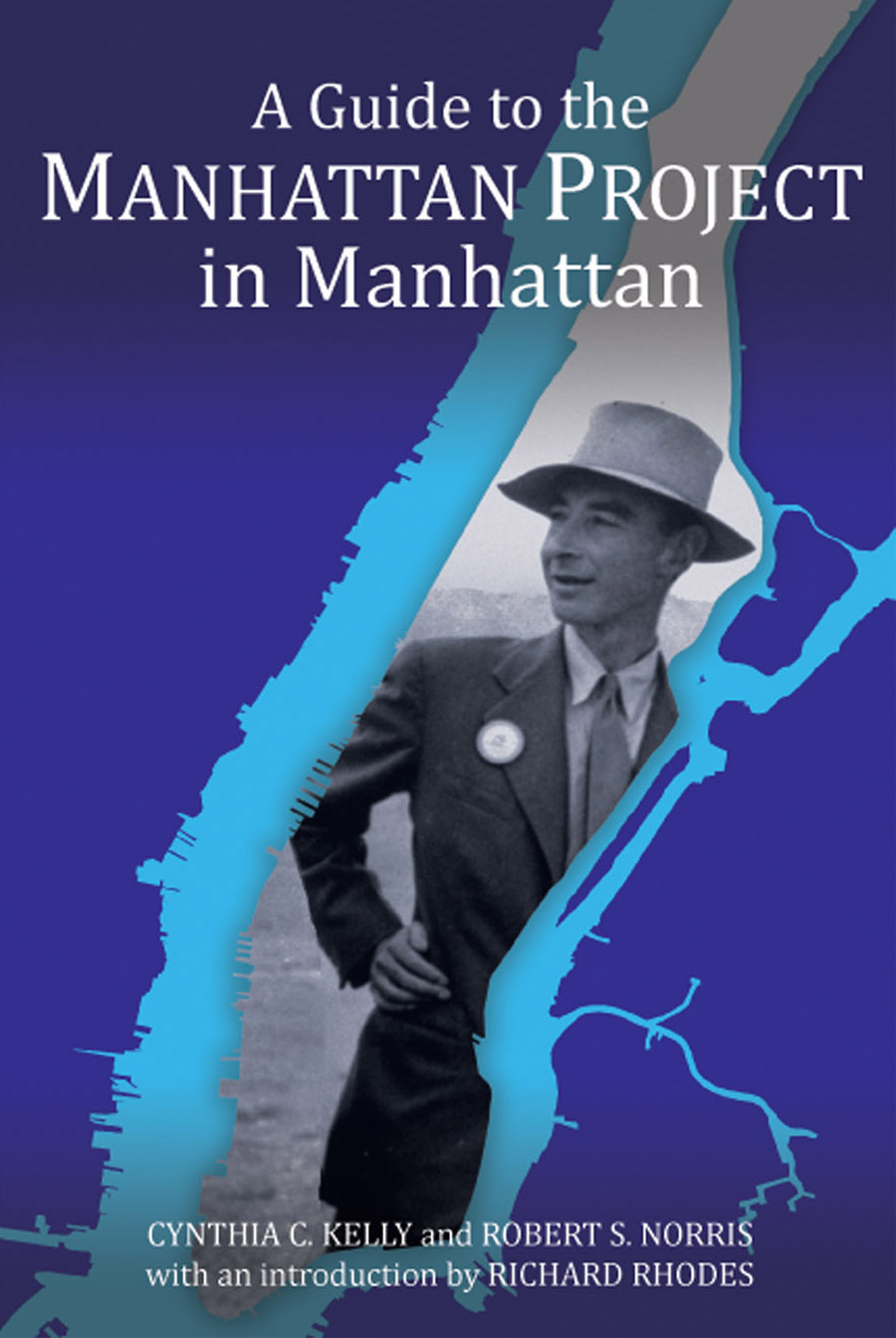

To coincide with the opening of the New-York Historical Society’s exhibition WWII & NYC, the Atomic Heritage Foundation has released a new expanded Guide to the Manhattan Project in Manhattan. Following the guide, readers can discover top-secret sites in Manhattan where work on the first atomic bombs took place—in buildings hidden in plain sight.

The Manhattan Project is usually associated with Los Alamos, New Mexico where J. Robert Oppenheimer directed the scientific laboratory. But the first offices of the Manhattan Project were actually in Manhattan, at 270 Broadway. So the Army Corps of Engineers called it the Manhattan Engineer District (MED) and the name “Manhattan Project” took hold.

“What’s most interesting is that there was an incredible amount of top-secret activity that happened all around Manhattan. Who would believe that 5,000 were working on the project? General Leslie Groves, who directed the entire project, came here nearly 50 times in three years,” commented Robert S. Norris, co-author of the guide and author of Racing for the Bomb.

Originally published as a shorter, black-and-white edition in 2008, the revamped guide gives a full-color, in depth look at ten sites that figured in the unfolding of the Manhattan Project. For example, the stately Woolworth Building was home to the Kellex Corporation, an entity of M. W. Kellogg, responsible for the massive gaseous diffusion plant known as “K-25” built in Oak Ridge, Tennessee.

The Woolworth Building also was home for a time to scientist members of the British Mission—including the infamous Klaus Fuchs. Cindy Kelly, co-author of the guide, explained, “Fuchs’ espionage started here and continued throughout the war. Eventually, he provided the USSR an invaluable blueprint for building the bomb.”

At Columbia University, Nobel Prize-winning scientist Enrico Fermi and his colleagues carried out cutting-edge research. On January 25, 1939, in the basement of Columbia University’s Pupin Hall, physicists used a cyclotron or “atom smasher” to replicate the recently discovered phenomenon of nuclear fission—the first time fission was witnessed in the United States. On loan from the Smithsonian, a 15-foot portion of the cyclotron will be featured in the NYHS’s exhibition.

For a critical period of time, New York City was where high-grade uranium ore from the Belgian Congo was stored. Edgar Sengier, director of a mining company in the Belgian Congo, fled Belgium just before the Germans invaded. To keep the ore in the Congo out of German hands, he shipped nearly 1,250 metric tons of uranium ore—half the uranium stock available in Africa—to Staten Island. A crucial ingredient in making an atomic bomb, the ore was a fortuitous windfall for the Manhattan Project.

In April 1945, Groves asked the managing editor of the New York Times, then headquartered in the Times Square Building, to provide William L. Laurence to write about the project. From his unique position, Laurence witnessed key historic moments, including the Trinity test on July 16, 1945 and the Nagasaki bomb on August 9, 1945.

In May 1945, Laurence drafted a speech for President Truman to deliver upon the dropping of the first atomic bomb. While Groves did not approve the speech, the guidebook includes excerpts of the only surviving copy of Laurence’s draft. Recognizing the promises of atomic energy, Laurence predicted “a new era of prosperity.”