Since the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, people in the United States and around the world have reacted to the atomic bomb with joy, devastation, hope, fear, and many other emotions. We have used cultural expressions to convey these sentiments, a phenomenon known as atomic culture. Atomic culture has manifested itself in popular culture, such as films, music, and fashion, and in high culture, such as literature, poetry, and theater. Atomic culture is also prevalent in the daily lives of Americans, becoming so ordinary that we don’t even notice the extent to which the bomb has permeated our society.

The Atomic Craze

Only days after the bombing of the Hiroshima, “atom bomb dancers” appeared in Los Angeles theaters while the Washington Press Club sold an “Atomic Cocktail.” In New York City, a jewelry store even advertised, “BURSTING FURY – Atomic Inspired Pin and Earring. New fields to conquer with Atomic jewelry. The pearled bomb bursts into a fury of dazzling colors in mock rhinestones, emeralds, rubies, and sapphires. . . . As daring to wear as it was to drop the first atom bomb.” General Mills soon created the “Atomic ‘Bomb’ Ring” in cereal boxes for children, telling them to look in the “sealed atom chamber in the gleaming aluminum warhead and see genuine atoms SPLIT to smithereens!” (By the Bomb’s Early Light 11)

Hollywood filmmakers hurried to include the atomic bomb in their movies. The House on 92nd Street, released in September 1945, was the first, briefly mentioning “Process 97, the secret ingredient of the atomic bomb” (Fallout 200). 1947 saw the release of The Beginning or the End, which told the story of the Manhattan Project, albeit with wildly inaccurate scientific details as atomic secrets were at the time classified.

The bomb quickly appeared in music as well. In December 1945, Karl and Harty recorded “When the Atom Bomb Fell,” a song which reflected newfound American power:

Smoke and fire it did flow through the land of Tokyo

There was brimstone and dust everywhere

When it all cleared away there the cruel Japs did lay

The answer to our fighting boys’ prayers

Yes, Lord, the answer to our fighting boys’ prayers

Around the same time, Lyle Griffin founded the “Atomic Records” label. In 1947, the Five Stars released the hit song “Atom Bomb Baby,” which used the bomb as a metaphor for sexuality.

The atomic bomb also emerged in comic books. In November/December 1945, Headline Comics created a series centered around Adam Mann, who accidentally ingests heavy water with U-235 in it. He becomes “Atomic Man,” a human atomic bomb, and proclaims, “I could use my power to crush every evil influence in the world” (Szasz 52). In a comic from October 1946, Superman drinks a poison to save Lois Lane, making him temporarily insane. He then accidentally flies into the atomic bomb test at Bikini Atoll, clearing his head.

The Bikini Atoll tests also had an important role in influencing fashion. In June 1946, French designer Jacques Heim unveiled a new swimsuit called the “atom,” which he advertised as “the world’s smallest bathing suit.” His competitor, Louis Réard, countered in July with the bikini, named for the site of the tests conducted only a month earlier in the Marshall Islands. (Réard in turn advertised his swimsuit as “smaller than the world’s smallest bathing suit.”)

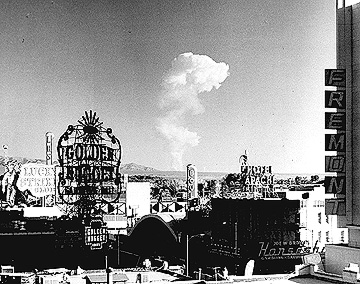

The atomic craze eventually expanded to include tourism. In 1951, the United States began conducting nuclear tests in Nevada, roughly 65 miles from Las Vegas, which as a result became an attractive tourist destination. “Dawn parties” were held at casinos for visitors to stay up to see the tests, while the Nevada Chamber of Commerce gave out calendars which listed the upcoming schedule. Pinups were sold of “Miss Atomic Blast,” who radiated “loveliness instead of deadly atomic particles.” Beauty pageants were even held to crown “Miss Atomic Bomb,” with the winner dressed in a fluffy white dress shaped like a mushroom cloud.

The mushroom cloud would itself come to symbolize this early era of atomic fantasy. Rather than being dangerous, it represented power, strength, and sexuality. The Atomic Café in Los Angeles and Atomic Liquors in Las Vegas, for example, had neon signs shaped like a mushroom cloud. Nevada’s Clark County (which included Las Vegas) even changed its official seal to include a mushroom cloud.

Cultural Warnings

Early American cultural reactions to the bomb were not all positive, however. In Theodore Sturgeon’s 1946 story “Memorial,” the main character, a scientist, wants an end to the “scream and crash of bombs and the soporific beat of marching feet.”

He ultimately sets off an atomic bomb as a warning of the “misuse of great power.” The same year, physicist Louis Ridenour wrote Pilot Lights of the Apocalypse, a one-act play in which the United States puts thousands of atomic bombs into satellite orbit only to discover that many others are already circling the Earth. A chain of nuclear destruction follows.

Warnings about the bomb also appeared in poetry, such as William Rose Benét’s “God’s Fire” (By the Bomb’s Early Light 245):

Raging inferno, consuming lava pit,

Fury of flame, with life’s foundations split

Time was, Time is! How fatefully the sound

Time shall be! tolls. Prometheus is unbound.

Among the most iconic works of the period was Ray Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles, originally published from 1946 to 1950 as a collection of short stories. In “The Watchers,” human colonizers on Mars watch as “Earth seemed to explode, catch fire, and burn.” A short time later they see “great Morse-code flashes” which transmit the message: “AUSTRALIAN CONTINENT ATOMIZED IN PREMATURE EXPLOSION OF ATOMIC STOCKPILE. LOS ANGELES, LONDON BOMBED. WAR. COME HOME. COME HOME. COME HOME.” In “There Will Come Soft Rains,” robots in a futuristic house make breakfast, announce the weather, and clean – but no people are present. Only “the five spots of paint—the man, the woman, the children, the ball—remained. The rest was a thin charcoaled layer.” The Martian Chronicles was read across the United States and has appeared in film, radio, television, comics, and even opera.

1951 saw the release of The Day the Earth Stood Still, a classic film which was remade in 2008. An alien, Klaatu, comes in a flying saucer to Washington, D.C. In his first appearance, Klaatu announces, “We have come to visit you in peace, and with good will,” and is promptly shot by an officer in the U.S. Army. In a speech later in the movie, Klaatu explains why he has come to visit Earth:

1951 saw the release of The Day the Earth Stood Still, a classic film which was remade in 2008. An alien, Klaatu, comes in a flying saucer to Washington, D.C. In his first appearance, Klaatu announces, “We have come to visit you in peace, and with good will,” and is promptly shot by an officer in the U.S. Army. In a speech later in the movie, Klaatu explains why he has come to visit Earth:

“The universe grows smaller every day and the threat of aggression by any group, anywhere, can no longer be tolerated. There must be security for all, or no one is secure. Now this does not mean giving up any freedom, except the freedom to act irresponsibly. It is no concern of ours how you run your own planet, but if you threaten to extend your violence, this earth of yours will be reduced to a burned out cinder. Your choice is simple: join us and live in peace, or pursue your present course and face obliteration. We shall be waiting for your answer. The decision rests with you.”

The fear of atomic destruction would only grow more pronounced in popular culture for the years to come.

The Age of Fallout

On March 1, 1954, the United States tested its largest bomb ever, “Castle Bravo.” After the explosion, the wind spread radioactive particles east, affecting several inhabited atolls, including Rongelap, Utirik, and Ailinginae. U.S. sailors observing the test and servicemen stationed on Rongerik Atoll were also exposed to radiation. Furthermore, fallout reached a Japanese fishing boat named Daigo Fukuryū Maru or “Fifth Lucky Dragon,” located 80 miles east of the test site. All 23 members of the crew were exposed to radiation, and they brought irradiated fish back to Japan, causing a panic.

On March 1, 1954, the United States tested its largest bomb ever, “Castle Bravo.” After the explosion, the wind spread radioactive particles east, affecting several inhabited atolls, including Rongelap, Utirik, and Ailinginae. U.S. sailors observing the test and servicemen stationed on Rongerik Atoll were also exposed to radiation. Furthermore, fallout reached a Japanese fishing boat named Daigo Fukuryū Maru or “Fifth Lucky Dragon,” located 80 miles east of the test site. All 23 members of the crew were exposed to radiation, and they brought irradiated fish back to Japan, causing a panic.

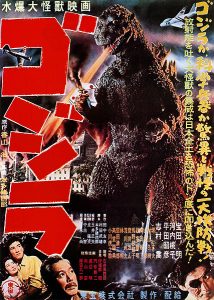

Castle Bravo had a marked effect on atomic culture by popularizing the term “fallout,” a word not used even by scientists until 1948, to describe the radioactive particles caused by a nuclear explosion. The same year, 1954, the first Godzilla film was released in Japan. The story follows the giant monster, Godzilla, who is disturbed from his deep-ocean sleep by hydrogen bomb testing and begins to attack Japan. As producer Tomoyuki Tanaka would explain, “The theme of the film, from the beginning, was the terror of the Bomb. Mankind had created the Bomb, and now nature was going to take revenge on mankind” (Tsutsui 18). Godzilla has remained a cultural icon, appearing in more than 30 films (including three from Hollywood) as well as in television, literature, comics, and video games.

Mutant creatures also appeared in American popular culture. The 1954 film Them! features giant mutant ants in New Mexico, where it is discovered that they are the product of radiation from Los Alamos. In Attack of the Crab Monsters (1957), scientists studying radiation on an island are attacked by giant mutant crabs. Even Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds (1963), in which flocks of killer birds attack humans, reflects similarly if not as overtly on nuclear fears. Hitchcock later spoke of the movie’s characters as “victims of Judgment Day,” and, as in Godzilla, warned not to “mess about or tamper with nature” (Henrikson 302).

Not all mutants of the fallout era were portrayed adversely, however. The Fantastic Four, a superhero team who gained their powers after radiation exposure in outer space, first appeared in 1961. 1962 saw the introduction of one of the greatest comic book heroes of all time: Spider-Man. When a spider falls into teenager Peter Parker’s “radioactive ray gun” and bites him, he gains extraordinary powers. Spider-Man’s enemy is nuclear scientist Otto Octavius, who after having tentacles welded onto his body during an atomic accident becomes “Dr. Octopus.” The same year, Marvel released the first issue of The Incredible Hulk, in which Dr. Bruce Banner is transformed after exposure to radiation.

A different theme of the fallout era in popular culture was atomic armageddon. Nevil Shute’s novel On the Beach was published in 1957 and made into a film in 1959. The story opens after a nuclear war has devastated most of the world. The only safe place left is Australia, and radioactive fallout will reach it in a matter of months. Faced with certain death, the characters struggle to find meaning in their lives. One young woman protests, “It’s not fair. No one in the Southern Hemisphere ever dropped a bomb, a hydrogen bomb or a cobalt bomb or any other sort of bomb. We had nothing to do with it. Why should we have to die because other countries nine or ten thousand miles away from us wanted to have a war? It’s so bloody unfair.”

In 1960, Walter M. Miller published A Canticle for Leibowitz, a post-apocalyptic science fiction novel which begins hundreds of years after a nuclear war known as the “Flame Deluge.” The story centers around a group of monks, the Order of Leibowitz, who protect what little knowledge remains in the world but in doing so eventually open the door for another Flame Deluge. Nuclear war is inevitable, despite the claims of the Order’s Reverend Father: “Brothers, let us not assume that there is going to be war. Let’s remind ourselves that Lucifer [the Bomb] has been with us—this time—for nearly two centuries. And was dropped only twice, in sizes smaller than a megaton. We all know what could happen, if there’s war… Only a race of madmen could do it again.”

The 1964 film Fail Safe deals with the issue of nuclear crisis in government. In the movie, American planes armed with nuclear weapons circle the Soviet Union (a strategy for second-strike capabilities that was actually used at the time). When they don’t stop at their “fail-safe” points due to an electronic error, however, nuclear war seems imminent. The American President, played by Henry Fonda, tries to stop them and ultimately orders the bombing of New York City to prove to the Soviets that it was a mistake. Fail Safe was made into a live-action movie starring George Clooney in 2000.

Civil Defense

The age of fallout also saw the rise of civil defense, the training of civilians to be prepared in the event of an attack. This notion was encouraged by the U.S. government and by American popular culture. After the United States tested its first hydrogen bomb on November 1, 1952, Newsweek reported, “All the reports and all the statistics added up to one grim conclusion: In an atomic attack, the front would be everywhere. Every home, every factory, every school might be the target. Nobody would be secure in the H-bomb age” (Henrikson 90).

The age of fallout also saw the rise of civil defense, the training of civilians to be prepared in the event of an attack. This notion was encouraged by the U.S. government and by American popular culture. After the United States tested its first hydrogen bomb on November 1, 1952, Newsweek reported, “All the reports and all the statistics added up to one grim conclusion: In an atomic attack, the front would be everywhere. Every home, every factory, every school might be the target. Nobody would be secure in the H-bomb age” (Henrikson 90).

In response to this threat, the government encouraged the American public to build fallout shelters in case of a nuclear attack. In a 1961 radio address, President Kennedy asserted, “In the event of an attack, the lives of those families which are not hit in a nuclear blast and fire can still be saved – if they can be warned to take shelter and if that shelter is available. We owe that kind of insurance to our families – and to our country.” The government also created numerous short civil defense films. To watch one such film from 1963, click here.

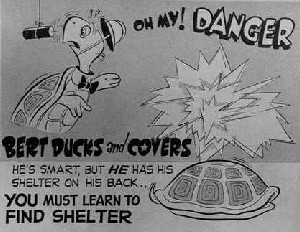

The government also instituted civil defense training for children. Although it predated the age of fallout, Duck and Cover (1952) featured the animated cartoon of “Bert the Turtle,” an icon of the civil defense era. Children practiced “duck and cover” exercises regularly in school. As activist Todd Gitlin remembered:

Every so often, out of the blue, a teacher would pause in the middle of class and call out, “Take cover!” We knew, then, to scramble under our miniature desks and to stay there, cramped, heads folded under our arms, until the teacher called out, “All clear!” Who knew what to believe? Under the desks and crouched in the hallways, terrors were ignited, existentialists were made. Whether or not we believed that hiding under a school desk or in a hallway was really going to protect us from the furies of an atomic blast, we could never quite take for granted that the world we had been born into was destined to endure. (109)

Civil defense also made its way to Hollywood. During a Cabinet meeting in December 1961, Leo Hoegh, the federal administrator of civil defense, criticized On the Beach as “very harmful because it produced a feeling of utter hopelessness, thus undermining OCDM’s [Office of Civil Defense Management] efforts to encourage preparedness.” State Department and U.S. Information Agency analysis added that its “strong emotional appeal for banning nuclear weapons could conceivably lead audiences to think in terms of radical solutions rather than practical safeguarded disarmament measures” (Fallout, 110).

The U.S. government preferred Hollywood films such as Panic in the Year Zero (1962). In the movie, the Baldwin family is going on a trip when they see strange flashes of light and then hear via CONELRAD (CONtrol of ELectronic RADiation, the emergency broadcast system used during this era) that Los Angeles has been bombed. Harry, the father, knows what to do in this emergency. He gathers supplies quickly, gets off the road, and keeps his family safe. At the end, the family is stopped by men with machine guns who turn out to be the U.S. military. “Thank God! It’s the Army!” declares Harry.

Counterculture

During the Cold War, a backlash appeared against the idea that preparedness in the form of civil defense could protect the United States from an atomic attack. Satirist Tom Lehrer, for example, wrote the song “We’ll All Go Together When We Go” in 1959:

No more ashes, no more sackcloth.

And an armband made of black cloth

Will some day never more adorn a sleeve.

For if the bomb that drops on you

Gets your friends and neighbors too,

There’ll be nobody left behind to grieve.

The Twilight Zone also offered criticism of the fallout shelter obsession in the 1961 episode “The Shelter.” When an imminent attack is announced through CONELRAD, Bill Stockton takes his family into the well-stocked shelter he has built in his basement. The family’s neighbors, who have no such shelters, beg him to let them in before eventually breaking down the door. After another announcement reveals that the reported attack is only harmless satellites, everyone rejoices. One of the neighbors offers to pay for the damages, and Bill Stockton replies:

I wonder if anyone of us has any idea what those damages really are. Maybe one of them is finding out what we’re really like when we’re normal; the kind of people we are just underneath the skin. I mean all of us: a bunch of naked wild animals, who put such a price on staying alive that they’d claw their neighbors to death just for the privilege. We were spared a bomb tonight, but I wonder if we weren’t destroyed even without it.

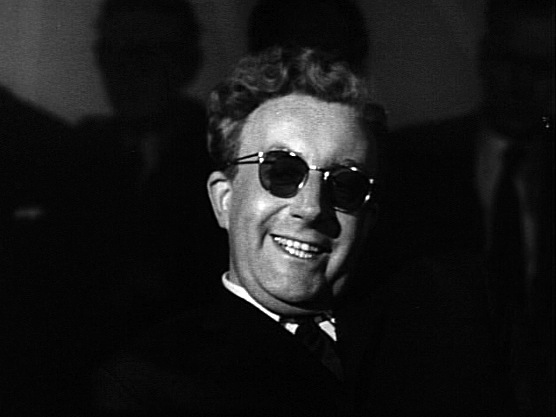

No work better exemplified the pushback against civil defense, however, than Stanley Kubrick’s 1964 black comedy Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb. As with Fail Safe, the story centers around a nuclear crisis after American planes are inadvertently sent to attack the Soviet Union. It is revealed that the Soviets have a “doomsday machine” set to attack the United States should the Americans launch a first strike, and it cannot be disabled for any reason.

No work better exemplified the pushback against civil defense, however, than Stanley Kubrick’s 1964 black comedy Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb. As with Fail Safe, the story centers around a nuclear crisis after American planes are inadvertently sent to attack the Soviet Union. It is revealed that the Soviets have a “doomsday machine” set to attack the United States should the Americans launch a first strike, and it cannot be disabled for any reason.

The film openly mocks United States government policy, including deterrence theory. The title character, Dr. Strangelove, is an ex-Nazi nuclear advisor loosely based on RAND Corporation expert Herman Kahn (author of On Thermonuclear War, which references the doomsday machine) and Wernher von Braun (a German physicist who developed rockets for the Nazis during World War II and later came to work for the United States). As Dr. Strangelove explains, “Deterrence is the art of producing in the mind of the enemy the fear to attack. And so because of the automated and irrevocable decision making process which rules out human meddling, the doomsday machine is terrifying, simple to understand, and completely convincing.”

The final minutes of the film also mock the idea that fallout shelters could be used to survive nuclear war. Dr. Strangelove suggest building deep mineshafts to survive (complete with a 10:1 female-to-male ratio in order to repopulate), while one of the generals warns that the Soviets could do the some, potentially creating a “mineshaft gap” (a reference to the feared “missile gap” between American and Soviet nuclear forces). The movie ends with footage of American nuclear tests while the cheerful song “We’ll Meet Again Someday” plays. Dr. Strangelove became a cultural icon, receiving four Academy Award nominations (including Best Director for Kubrick), and was selected by the Library of Congress for preservation in the National Film Registry in 1989.

Atomic Culture Under Reagan

The late 1960s and the 1970s saw a decline of nuclear themes in American popular culture. While 64% of Americans in 1959 said that nuclear war was the most pressing issue for the United States, by 1964 that number had dropped to just 16% (By the Bomb’s Early Light 355). The successful negotiation of the Cuban Missile Crisis and the subsequent establishment of a permanent White House-Kremlin hotline, the 1963 Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, and the distraction of the Vietnam War were all contributing factors to this phenomenon. Historian Paul Boyer called this period of atomic culture “the Era of the Big Sleep.”

The late 1960s and the 1970s saw a decline of nuclear themes in American popular culture. While 64% of Americans in 1959 said that nuclear war was the most pressing issue for the United States, by 1964 that number had dropped to just 16% (By the Bomb’s Early Light 355). The successful negotiation of the Cuban Missile Crisis and the subsequent establishment of a permanent White House-Kremlin hotline, the 1963 Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, and the distraction of the Vietnam War were all contributing factors to this phenomenon. Historian Paul Boyer called this period of atomic culture “the Era of the Big Sleep.”

Nevertheless, atomic culture returned in earnest along with Cold War tensions under the presidency of Ronald Reagan during the 1980s. Films imagining nuclear war were once again produced, such as World War III (1982), The Day After (1983), Testament (1983), The Dead Zone (1983), Countdown to Looking Glass (1984), When the Wind Blows (1986), and Miracle Mile (1988). The 1984 bestselling novel The Hunt for Red October (made into a 1990 movie starring Sean Connery and Alec Baldwin) tells the story of a Soviet submarine captain who realizes his submarine is going to launch a first nuclear strike and thus tries to defect and stop nuclear war.

Other works were more openly critical of Reagan-era policies. Musicians such as James Taylor, Bonnie Raitt, Bruce Springsteen, and Jackson Browne collaborated on the 1980 concert film No Nukes. The Atomic Cafe, a 1982 documentary, is a mash-up of excerpts from old news clips and government films which show the ridiculous nature of the civil defense era. The film uses black humor to make its point (“Watched from a safe distance, this explosion is one of the most beautiful sights seen by man,” declares an officer in a training video), and it implies criticism of the returned threat of nuclear war.

Dr. Seuss wrote The Butter Battle Book (1984), a parable on the dangers of the arms race. It also comments on the fickle nature of renewed tensions with the Soviet Union, as it features the supposedly bitter divide between the Yooks (who eat their bread with the butter-side up) and the Zooks (who eat it with the butter-side down).

The 1980s also saw elements of nuclear nostalgia. There was a renewed interest in the Manhattan Project (1985 marked the 40th anniversary of the Trinity Test and the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki), resulting in the production of films such as Day One (1989) and Fat Man and Little Boy (1989). Other works once again used nuclear themes. In Back to the Future (1985), Doc Brown uses plutonium to build a time machine. In The Manhattan Project (1986), teenager Paul Stephens steals plutonium for his entry in a science fair: “the first privately produced nuclear device in the history of the world.”

Post-Cold War

The nuclear nostalgia which began in the late 1980s has continued to the present day. This can be seen, for example, in the popular, long-running television show The Simpsons. Homer Simpson works at a nuclear power plant, “Blinkie” the three-eyed fish (the product of nuclear waste from the plant) appears frequently, and Bart Simpson’s favorite comic book character is “Radioactive Man” and his sidekick “Fallout Boy.” Movie remakes of comic book classics such as Spider-Man (2002), The Incredible Hulk (2004), and Fantastic Four (2015) have also marked the modern era.

Since the end of the Cold War, other works have reflected on different types of apocalypse. One example of this is the 1996 science fiction movie Independence Day, which won the Academy Award for Best Visual Effects and was at the time the second highest-grossing film of all time, earning over $800 million. In the film, humans must band together to fight alien invaders. As producer Dean Devlin noted, “Our movie is pretty obvious. The closest we get to a social statement is to play upon the idea that as we approach the millennium, and we’re no longer worried about a nuclear threat, the question is, Will there be an apocalypse, and if so, how will it come?” (Fallout 225).

The theme of nuclear terrorism has also appeared frequently during the last two decades. In Austin Powers: International Man of Mystery (1996), Dr. Evil says, “Oh, hell, let’s just do what we always do. Let’s hijack some nuclear weapon and hold the world hostage” (Zeman and Amundson 132). Other films have also addressed this issue, such as The Peacemaker (1997), Bad Company (2002), and the James Bond film The World Is Not Enough (1999).

Additionally, The Dark Knight Rises (2012), the third installment in Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight Trilogy, centers on a nuclear threat. The film’s antagonist, Bane, threatens to detonate a thermonuclear device in the heart of Gotham City if officials attempt to interfere with his plans for societal upheaval. The Dark Knight Rises grossed over $1.08 billion, making it the 19th highest grossing movie of all time.

A number of cultural products have grappled with the still-present legacy of the atomic age. Thirteen Days (2000) recounts the chilling suspense experienced during the Cuban Missile Crisis. The film gives a dramatized account of President John F. Kennedy and his advisors as they debate solutions to the thermonuclear confrontation with the Soviet Union.

Another example is the 2016 Japanese anime film In This Corner of the World. It is the story of a fictional young woman named Suzu who lives on the outskirts of Hiroshima in the years leading up to the Second World War. The film contrasts the beauty and struggle of everyday life with the brutality of war. AHF’s review of In This Corner of the World can be found here.

The prospect of nuclear war still lingers in the works of popular music artists. Among others, artists such as Mark Owen, Iron Maiden, The Postal Service, Radiohead, and New Politics have all released highly regarded songs since 2000 expressing anxiety, outrage, and ominous submission to nuclear war.

Atomic culture in the United States will without a doubt continue to develop in the future and will likely never disappear entirely. Recent films such as The Avengers (2012), which ends with the superheroes saving New York City from a nuclear bomb, and Pacific Rim (2013), in which an atomic bomb is used to close an alien portal, demonstrate a continued cultural interest in all things nuclear. Renewed tensions with Russia as well as the nuclear threat from North Korea may very well make their way into atomic culture in the years to come.