The U.S. military uses the term “Broken Arrow” to refer to an accident that involves nuclear weapons or nuclear weapons components, but does not create the risk of nuclear war. A Broken Arrow is different from a “Nucflash,” which refers to a possible nuclear detonation or other serious incident that may lead to war.

As the U.S. and the Soviet Union developed and enhanced their arsenals during the Cold War arms race, both experienced a number of nuclear accidents. Since 1950, the Defense Department has reported 32 Broken Arrows. Three of the most notable U.S. incidents involving thermonuclear weapons are detailed below.

Kirtland Air Force Base (1957)

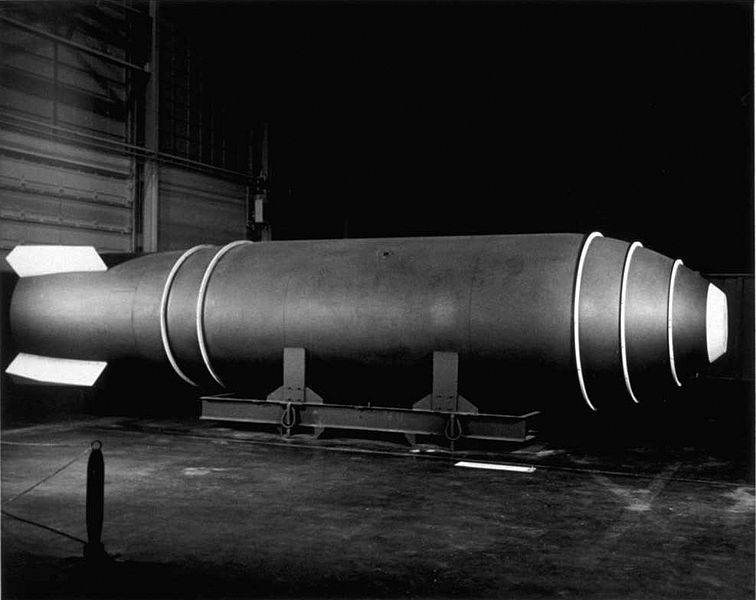

At 11:50 a.m. local time on May 22, 1957, a B-36 aircraft jettisoned an unarmed Mark 17 ten-megaton hydrogen bomb over Albuquerque, New Mexico. The thermonuclear device, weighing 42,000 pounds, was being transported from Biggs Airfield in Texas to Kirtland Air Force Base just miles south of Albuquerque.

Accounts of what caused the incident vary, but one version suggests that a crewmember in the bomb bay was jolted by sudden turbulence. He grabbed hold of the manual bomb release lever to steady himself, causing the weapon to fall through the closed bomb bay doors and plummet to earth.

The nuclear chain reaction necessary to set off the bomb did not occur because the bomb’s fissionable plutonium component was stored separately aboard the aircraft. However, the device’s conventional explosives detonated, leaving a crater 12 feet deep and 25 feet wide on an uninhabited area of land owned by the University of New Mexico. The Field Command division of the Armed Forces Special Weapons Project, responsible for recovery and cleanup operations, reported the incident’s only casualty was a nearby grazing cow, and found that radioactive material did not spread beyond one mile of the crater.

The incident was revealed to the public for the first time in the 1980s, after the Air Force released declassified documents under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA). AHF Board member Robert S. Norris, then a research associate for the National Resources Defense Council, remarked that the Mark 17 “is possibly the most powerful bomb we ever made.”

B-52 Crash in Goldsboro, NC (1961)

In the early morning of January 24, 1961, a B-52 bomber carrying two Mark 39 nuclear weapons crashed near Goldsboro, North Carolina. The aircraft was a part of a Strategic Air Command (SAC) mission designed to keep a significant number of bombers in air at all times, so that in the event of a Soviet first strike they would not be damaged or destroyed. The operation necessitated that the aircraft be refueled in mid-air.

At midnight on January 23-24th, the B-52 rendezvoused with a tanker to refuel. The tanker crew observed that the aircraft was leaking fuel from its right wing, and notified its commander, Major Walter Scott Tulloch. SAC instructed Tulloch to assume a holding position until most of the plane’s fuel was lost and prepare for an emergency landing. However, the leak quickly worsened, and as the plane descended, the pilots began to lose control of the aircraft. The crew attempted to eject. Of the eight crew members on board, five were able to parachute to safety. Sergeant Francis Roger Barnish, Major Eugene Holcombe Richards, and Major Eugene Shelton were killed.

At midnight on January 23-24th, the B-52 rendezvoused with a tanker to refuel. The tanker crew observed that the aircraft was leaking fuel from its right wing, and notified its commander, Major Walter Scott Tulloch. SAC instructed Tulloch to assume a holding position until most of the plane’s fuel was lost and prepare for an emergency landing. However, the leak quickly worsened, and as the plane descended, the pilots began to lose control of the aircraft. The crew attempted to eject. Of the eight crew members on board, five were able to parachute to safety. Sergeant Francis Roger Barnish, Major Eugene Holcombe Richards, and Major Eugene Shelton were killed.

The crash resulted in the release of two 3-4 megaton hydrogen bombs. One of the bombs fell straight down and crashed into a muddy field at a rate of 700 mph, plunging the weapon deep into the ground. Its tail was found 20 feet below the surface. Though complete excavation of the weapon was abandoned, much of its nuclear material was recovered. Some uranium remains at the crash site, where the US Air Force performs regular inspection to test for radioactive contamination. To date no radiation has been detected.

The second weapon’s landing remains controversial to this day. Unlike the first, the second bomb’s parachute opened, indicating that its arming sequence was initiated. Eventually, the bomb’s parachute got stuck on a tree, leaving the weapon mostly intact.

Today, experts differ on how close the weapon came to detonating and how many of the arming procedures it underwent. One analysis holds that the weapon only did not detonate because its arm/safe switch, controlled by the pilot, was still set on safe. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara reported that, “by the slightest margin of chance, literally the failure of two wires to cross, a nuclear explosion was averted.” A 1969 expert analysis reiterated, “One simple, dynamo-technology, low voltage switch stood between the United States and a major catastrophe!” Others contend that the bomb was in fact not close to detonating.

Bill Stevens, a retired nuclear weapons safety engineer at Sandia National Laboratories, sums up the dispute: “Some people could say, hey, the bomb worked exactly like designed. Others can say, all but one switch operated, and that one switch prevented the nuclear detonation.”

A road marker labeled “Nuclear Mishap” in Eureka, NC, a town three miles north of the crash site, commemorates the incident today.

Palomares, Spain (1966)

On the morning of January 17, 1966, a B-52 bomber carrying four Mark 28 hydrogen bombs collided with a KC-135 refueling aircraft near Palomares, Spain. The B-52 was part of the United States Air Force’s Operation “Chrome Dome,” in which Strategic Air Command constantly flew bombers armed with thermonuclear weapons in order to provide the US with a first strike capability over the USSR in event of a “hot” confrontation.

The Collision

While flying at an altitude of 31,000 feet, the B-52 bomber approached the KC-135 tanker for a routine aerial refueling at around 10:30 am. However, the bomber’s incoming speed was too fast and caused the aircraft to collide with the tanker’s fueling boom. Major Larry G. Messinger, one of the B-52 co-pilots, recalled, “All of a sudden, all hell seemed to break loose.”

The collision caused an explosion that ignited the tanker, killing all four crew members on board. The B-52 started to break apart, and its unarmed thermonuclear payload, four 1.5 megaton bombs, was released. Three of the hydrogen bombs fell to the ground while the fourth landed in the Mediterranean Sea. Of the seven crew members aboard the bomber, four ejected and parachuted to safety while three were killed.

Manolo Gonzalez, a local villager, recounted, “I looked up and saw this huge ball of fire falling through the sky, the two planes were breaking into pieces.” Debris from the collision fell down on Palomares, but no one in the town was killed.

Recovery

Approximately 24 hours after the collision, U.S. servicemen and disaster control teams located, secured, and recovered the three hydrogen bombs that fell on land. One bomb deployed its parachute as designed and landed harmlessly, in what former Secretary of the Air Force Thomas C. Reed calls “a silent testimonial to the care of those who designed, engineered, and built those U.S. nukes.” However, the conventional explosives in two bombs went off, contaminating surrounding farms (see below).

The fourth bomb parachuted several miles off the coast and landed in the Mediterranean Sea. The U.S. Navy launched an intensive three-month search involving nearly 12,000 people, several ships, and two submarines, the Alvin and the Aluminaut.

On March 2, the United States was forced to publicly announce the incident and disclose the ongoing search for the missing hydrogen bomb. Six days later, U.S. Ambassador to Spain Angier Biddle Duke went for a swim in a nearby beach to prove the water was safe. He told reporters, “If this is radioactivity, I love it!”

The bomb was ultimately found and extracted from the ocean on April 7. The following day, reporters were permitted to photograph it aboard the U.S.S. Petrel. The New York Times reported it was the first time the U.S. military had displayed a nuclear weapon to the public.

Two years after the Palomares incident, SAC halted Operation Chrome Dome flights. The Navy’s recovery of the fourth bomb was dramatized in the 2000 film Men of Honor, starring Cuba Gooding Jr. and Robert De Niro.

Cleanup

The U.S. military launched Operation “Moist Mop” in Palomares to remove contaminated soil from the bombs’ release of plutonium. Author Barbara Moran describes, “To clean it up, they decided to remove the contaminated dirt from the most contaminated areas.” This involved removing topsoil from irradiated areas and shipping it to storage facilities in the United States.

The U.S. military launched Operation “Moist Mop” in Palomares to remove contaminated soil from the bombs’ release of plutonium. Author Barbara Moran describes, “To clean it up, they decided to remove the contaminated dirt from the most contaminated areas.” This involved removing topsoil from irradiated areas and shipping it to storage facilities in the United States.

Over the course of four months, more than 1,400 tons of soil, across 650 acres of land, was sent to an approved storage facility in Aiken, South Carolina. Additionally, medical treatment centers were set up to monitor residents who had been exposed to the plutonium. In the immediate wake of the incident, the US settled claims with residents of Palomares for $600,000. In recent years, a number of U.S. servicemen who participated in the cleanup have alleged that their exposure to plutonium has resulted in lifelong health problems.

Part of the area remains fenced off. In 2006, the Spanish Center for Energy Research (CIEMAT) discovered radioactive snails in the area. Subsequent analyses have continued to detect levels of plutonium in the soil. A 2006 State Department cable reveals that the Spanish government “believe[d] the remaining contamination might be more serious than heretofore believed” and that the US had spent $12 million, or approximately $300,000 every year to that point, to assist the Spanish in monitoring the contaminated area.

In 2015, Secretary of State John Kerry signed a “Statement of Intent” with Spain’s Foreign Minister, José Manuel Garcia-Margallo y Marfil, to assist Spain in completing the cleanup of Palomares. Secretary Kerry remarked, “What is Palomares? To the U.S. government, it remains the site of a tragic and embarrassing accident which held the attention of the world for a few long months in 1966…We have to build on today’s signing to take further action to resolve, once and for all, this very important issue.”