On March 1, 1954, the United States carried out its largest nuclear detonation, “Castle Bravo,” at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands. The Bravo shot was the first test of Operation Castle, a series of thermonuclear tests. The explosion was more than two and a half times greater than expected and caused far higher levels of fallout and damage than scientists had predicted.

The Bravo test used a device called “Shrimp,” which relied on lithium deuteride as its fuel. The explosion yielded 15 megatons of TNT and released large quantities of radioactive debris into the atmosphere that fell over 7,000 square miles. The explosion resulted in the radioactive contamination of the inhabitants of nearby atolls, U.S. servicemen, and the crew of a Japanese fishing trawler (“The Lucky Dragon”), which had gone unnoticed in the security zone around the blast. The incident was the worst radiological disaster in U.S. history and generated worldwide backlash against atmospheric nuclear testing.

The Test

The “Shrimp” weighed approximately 23,500 pounds and was based on the Teller-Ulam thermonuclear weapon design. The explosion occurred at 6:45am local time. The bomb was in a form readily adaptable for delivery by an aircraft and was thus America’s first weaponized hydrogen bomb.

Seconds after detonation, a mushroom cloud four and a half miles wide formed. It ultimately reached a height of 130,000 feet. The explosion left a crater on the ocean floor with a diameter of 6,500 feet and a depth of 250 feet. Castle Bravo was approximately 1,000 times more powerful than the “Little Boy” atomic bomb detonated over Hiroshima.

Radioactive Fallout

The Castle Bravo test was responsible for a significant amount of unintended radioactive contamination, augmented by unfavorable weather conditions and changes in wind patterns. Despite the increased risk of spreading fallout to nearby inhabited islands, Major General Percy Clarkson, commander of the military task force responsible for the test, and Dr. Alvin C. Graves, the scientific director of Operation Castle, ordered the test to continue as planned.

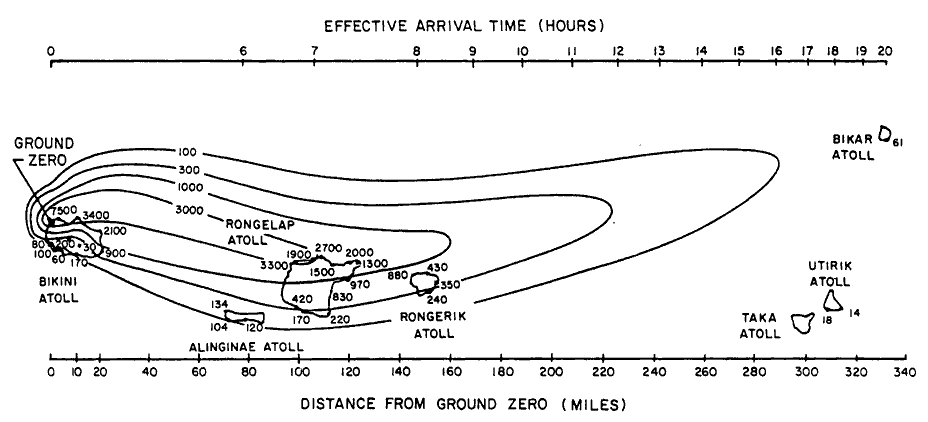

After the explosion, the wind spread radioactive particles east, affecting several inhabited atolls, including Rongelap, Utirik, and Ailinginae. U.S. sailors observing the test and servicemen stationed on Rongerik Atoll were also exposed to radiation.

The atoll of Rongelap was particularly affected. Jeton Anjain, Minister of Health and Senator in the Marshallese parliament, later testified, “Approximately five hours after the detonation, it began to rain radioactive fallout at Rongelap. Within hours, the atoll was covered with a fine, white, powder-like substance. No one knew it was radioactive fallout. The children played in the ‘snow.’ They ate it.”

The U.S. evacuated the inhabitants of Rongelap two days after the test. The people of Rongelap were relocated to Majuro, the capital of the Marshall Islands. Residents returned home in 1957, but were evacuated by the Greenpeace vessel Rainbow Warrior in 1985 due to concerns about lingering levels of radiation.

Wind shear and ocean currents spread fallout from the Castle Bravo explosion. Traces of radioactive material were later found in Japan, India, and Australia, as well as in parts of Europe and the United States.

Health Effects and Compensation

Within a week of the test, the U.S. launched a medical study on the effects of radiation on island inhabitants and provided medical care to people who had been exposed. Led by Eugene P. Cronkite of the National Naval Medical Center, the effort was called Project 4.1, or the “Study of Human Beings Exposed to Significant Beta and Gamma Radiation Due to Fall-out from High-Yield Weapons.” Researchers conducted numerous medical examinations of affected Marshallese, issued a number of (initially classified) reports, and published an article describing their findings in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Today, scholars have criticized Project 4.1 for not obtaining informed consent from the Marshallese. “The team conducting the study did not ask the Marshallese for their consent or even explain to them that a study was being conducted,” historian April Brown wrote in a 2014 article for Arms Control Today. “The Marshallese were told they were being treated for their various illnesses, but rarely was a translator present to explain what tests were being conducted or for what purpose. Marshallese were given pills to take with no accompanying explanation as to why they were supposed to take them.”

Researchers have conducted numerous subsequent studies on the health effects of Castle Bravo and the other 66 nuclear tests carried out by the U.S. in the Marshall Islands between 1946 and 1958. In 2010, National Cancer Institute experts reported, “As much as 1.6% of all cancers [approximately 170 cases] among those residents of the Marshall Islands alive between 1948 and 1970 might be attributable to radiation exposures resulting from nuclear testing fallout.” Marshallese who lived in northern atolls, including Rongelap and Utirik, received the highest radiation doses. On Rongelap, they “projected 55% of all cancers might be attributed to fallout exposure.” The researchers concluded, “The doses received by residents of the northern atolls were essentially due to a single test, Castle Bravo.”

According to the US Embassy in Majuro, since Castle Bravo, the United States has provided a total of more than $604 million to the affected atolls and communities. Adjusting for inflation, this is equal to $1.05 billion (2010 dollars), and includes medical treatment, health care costs, island rehabilitation efforts and investments, and resettlement funds.

In 1983, the U.S. and the Marshall Islands signed a Compact of Free Association, which allowed the Marshall Islands to become independent in 1986. The United States remains officially responsible for the security and defense of the Marshall Islands, but the Marshallese have complete sovereignty over their foreign relations. The two countries also reached a bilateral agreement that established the Marshall Islands Nuclear Claims Tribunal, designed to award compensation for cancers and other serious health effects, such as burns and birth defects, attributed to nuclear testing. The U.S. established a $150 million compensation trust fund.

However, many Marshallese and environmental activists dispute this figure. For example, a former public advocate for the Tribunal charges that the $150 million number for the trust fund “was completely pulled out of the air. There was no actual basis for it.” By the early 2000s, the tribunal lacked the necessary funds to disperse settlement payments fully. The original agreement allowed the Marshall Islands to petition for additional compensation given “changed circumstances,” but the U.S. Supreme Court rejected a petition by the Marshallese in 2010.

Today, the legacy of nuclear testing in the Marshall Islands remains contentious. In 2014, the Marshall Islands sued the world’s nine nuclear weapons states (the US, Russia, UK, France, China, India, Pakistan, North Korea, and Israel) over their failure to reduce their nuclear arsenals as called for in the 1968 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. The case was rejected in October 2016 by the International Court of Justice in The Hague.

The Lucky Dragon Incident

Approximately an hour and a half after the Castle Bravo test, fallout reached a Japanese fishing boat named Daigo Fukuryū Maru or “Fifth Lucky Dragon,” located 80 miles east of the test site. All 23 members of the crew, as well as their catch, were exposed to radiation. One crewmember died several months later; the cause of his death remains disputed. Fisherman Oishi Matashichi recalled seeing the explosion:

A yellow flash poured through the porthole. Wondering what had happened, I jumped up from the bunk near the door, ran out on the deck, and was astonished. Bridge, sky, and sea burst into view, painted in flaming sunset colors. I looked around in a daze; I was totally at a loss.

The irradiated fish brought home by the vessel entered the Japanese market, causing a panic and straining US-Japanese relations. “We had this enormous explosion of feeling against the United States for having exploded the bomb and exposing the Japanese nationals to its effects,” a U.S. diplomat remembered. “You could smell the fish markets in Japan for miles weeks afterward because they didn’t know where the fish had gone, they lost track of distribution. Even in Tokyo’s enormous fish market sold very few fish for weeks. It was a serious economic disruption in addition to being a psychological body blow to Japan.”

The Lucky Dragon incident made the Castle Bravo test, in the words of historian Alex Wellerstein, “extremely public.” The U.S. was forced to unveil some of the secrecy that previously surrounded nuclear testing. In a 2002 interview with AHF, physicist Ralph Lapp explained, “The story of the Lucky Dragon blew the lid off secrecy because the Atomic Energy Commission could not keep it a secret. This story had to be told…because radioactivity persisted and could deny territory to normal use. Furthermore, there was the fact that some of the chemicals in the fallout were highly toxic fission products and this could be a health hazard.”

Consequences

The United States was not the only country conducting atmospheric testing during this time, nor was it the only one to test in its territorial holdings. The Soviet Union tested its first atomic bomb in 1949 in Kazakhstan, and went on to test in Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and Ukraine as well. Further testing was conducted by the United Kingdom in Australia and in the Pacific Ocean beginning in 1952, and by France in Algeria and the South Pacific beginning in 1960.

Castle Bravo triggered a backlash around the world against atmospheric nuclear testing. Later in 1954, Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru called for a moratorium on testing or “standstill agreement” between the US and Soviet Union. He warned, “No country, no people, however powerful they might be, are safe from destruction if this competition in weapons of mass destruction and cold war continues.”

The reaction to the test demonstrated the growing influence of public opinion on nuclear policy. In 1955, the United Nations created the Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation, with the stated mandate “to assess and report levels and effects of exposure to ionizing radiation.” Since then, the UNSCEAR has issued regular reports to the UN General Assembly. Ultimately, Castle Bravo also proved to be an impetus for the 1963 Limited Test Ban Treaty between the US, UK, and the Soviet Union, which prohibited nuclear testing in the atmosphere, underwater, and in outer space.

In 1982, four United States servicemen affected by radioactive fallout from Castle Bravo sued the U.S. government, alleging a “conspiracy to cover up and conceal vital scientific information.” One of the veterans involved, Gene Curbow, explained how “a mixture of patriotism and ignorance” had kept him from speaking out before. While the truth of these allegations remains unproven, historians generally agree that the effects of Castle Bravo were in fact accidental.

The incident also had an important role in popular culture. As Wellerstein notes, Castle Bravo helped popularize the term “fallout” to describe the radioactive particles caused by a nuclear explosion. Subsequent films such as Godzilla and On the Beach reflected public concern over the dangers of nuclear arms.

Lapp reflected that Castle Bravo and other extremely powerful thermonuclear weapons marked a “historic change” in warfare. He said, “I think that the one lesson we have to learn is that because the weapons have such power we have entered a new era. These weapons have bisected human history.”

.jpg)