In 1964, China became the fifth country to possess nuclear weapons following the United States, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and France. Although the Chinese atomic bomb project was mostly independent, it greatly benefited from Soviet support and from Western sources.

Origins of the Program

After years of civil war, communist leader Mao Zedong established the People’s Republic of China in 1949. Mao soon visited Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin in Moscow, where the two signed the Sino-Soviet Treaty of Friendship and Alliance. Although China’s alliance with the Soviet Union would be short-lived, it played a crucial role in the success of the Chinese nuclear program during its early years.

Mao quickly faced intense hostility from the West, particularly the United States, which threatened nuclear strikes against China. After North Korea invaded South Korea in June 1950, Washington intervened in support of the South, while Beijing fought in support of the North. President Harry S. Truman subsequently ordered ten nuclear-armed B-29s to the Pacific fleet as his government seriously considered a nuclear strike. One proponent of nuclear action, General Curtis LeMay, argued in 1954, “I would drop a few bombs in proper places like China, Manchuria and Southeastern Russia. In those ‘poker games,’ such as Korea and Indo-China, we… have never raised the ante—we have always just called the bet. We ought to try raising sometime.”

Although no atomic bombs were ever used against China, the United States made similar threats after Mao offered Chinese support to the Viet Cong in French Indochina. President Dwight D. Eisenhower likewise considered using the bomb to protect Taiwan—nationalist opposition leader Chiang Kai-Shek had fled to the island in 1949—against Chinese aggression, signing the U.S.-Taiwan Mutual Defense Treaty in 1954. Mao officially authorized the Chinese atomic bomb project in January 1955, largely in response to the American nuclear threat. As Mao affirmed, “We need the atom bomb. If our nation does not want to be intimidated, we have to have this thing” (Chansoria 80).

Although no atomic bombs were ever used against China, the United States made similar threats after Mao offered Chinese support to the Viet Cong in French Indochina. President Dwight D. Eisenhower likewise considered using the bomb to protect Taiwan—nationalist opposition leader Chiang Kai-Shek had fled to the island in 1949—against Chinese aggression, signing the U.S.-Taiwan Mutual Defense Treaty in 1954. Mao officially authorized the Chinese atomic bomb project in January 1955, largely in response to the American nuclear threat. As Mao affirmed, “We need the atom bomb. If our nation does not want to be intimidated, we have to have this thing” (Chansoria 80).

Early Development

The Chinese nuclear program was aided by its considerable access to Western atomic secrets. For example, China may have benefited from the defection of American physicist Joan Hinton in 1948 (Reed and Stillman 87). Hinton had worked on the “Fat Man” plutonium implosion bomb at Los Alamos and witnessed the Trinity Test.

Additionally, Mao pushed for the return of the many Chinese scientists who studied in Europe and the United States. One such physicist was Qian Sanqiang—sometimes called “the father of the Chinese atomic bomb”—who studied at the Collège de France under French physicists Frédéric and Irène Joliot-Curie for over a decade. Qian returned to Beijing in 1948 and founded the China Institute of Atomic Energy. The Joliot-Curies were also directly supportive of the Chinese nuclear program; in 1951, Irène gave Chinese radiochemist Yang Chengzong ten grams of radium “to support the Chinese people in their nuclear research” (Chansoria 83).

China also received substantial support for its nuclear program from the Soviet Union. General Secretary Nikita Khrushchev visited Beijing in 1954, and in 1955 the two countries signed an agreement for “full [Soviet] assistance in the fields of nuclear physics and the peaceful uses of atomic energy” (Reed and Stillman 94). The Soviets allowed Chinese scientists to come study in the Soviet Union and agreed to provide China with nuclear reactors and a cyclotron. In return, the Chinese agreed to sell their surplus uranium to the Soviet Union.

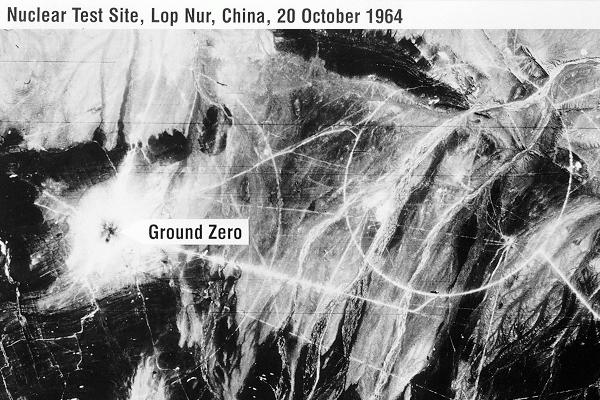

After the successful launch of Sputnik 1 in October 1957, Mao and Khrushchev signed an additional agreement: the New Defense Technical Accord. The Soviet Union promised to supply China with the R-2 short-range ballistic missile and even a prototype atomic bomb. In June 1958, a Soviet delegation led by E. A. Negin arrived in Beijing to explain to Chinese scientists “how a nuclear weapon is made” (Reed and Stillman 99). Soviet engineers also helped construct the fledgling Chinese nuclear complex, most notably the Northwest Nuclear Weapons Development Base in Haiyan, a research facility built as a replica of the Soviet closed city Arzamas-16. Other important sites included the Lanzhou uranium enrichment plant, the Jiuquan plutonium reactor, and the Lop Nur test site.

Progress on the atomic bomb program was hobbled, however, when Mao initiated his Great Leap Forward in 1958. The economic program, which collectivized Chinese agriculture, caused a famine that killed an estimated 20 to 30 million people. Research at the Northwest Nuclear Weapons Development Base slowed to a crawl, a situation exacerbated by the order to make Soviet equipment “more Chinese” (Reed and Stillman 98).

The Sino-Soviet Split

1959 saw the Sino-Soviet split, a diplomatic breakup which had far-reaching geopolitical implications, including the end of Soviet assistance to the Chinese nuclear program. Sino-Soviet relations began to rapidly deteriorate after Khrushchev’s 1956 secret speech to the Congress of the Communist Party in which he denounced the crimes of Joseph Stalin. Mao, who admired Stalin’s iron rule and cult of personality, took the speech as an affront to his regime.

In the years to come, Khrushchev began to doubt Mao’s sanity, particularly when it came to nuclear weapons. For example, Khrushchev was particularly concerned when Mao commented regarding nuclear war, “We have so many people. We can afford to lose a few. What difference does it make?” (Reed and Stillman 95). Mao, for his part, was growing increasingly distrustful of Khrushchev. In one instance, Mao arranged for a meeting with Khrushchev in his private swimming pool, knowing full well that the Soviet Premier could not swim.

In May 1959, Khrushchev decided, “Under no circumstances should the Soviet Union continue to transfer atomic secrets to the Chinese” (Reed and Stillman 101). The Soviets never delivered the prototype atomic bomb that they had promised, and the Negin delegation departed Beijing. The Sino-Soviet split sparked a period of intense paranoia in which China feared an attack on its nuclear facilities. After all, the Soviet Union—which had helped construct the Chinese nuclear complex—knew the precise location of every site. Beijing ordered the construction of a new, secret facility for weapons design at Zitong, which included many underground buildings.

Project 596

In the aftermath of the Sino-Soviet split, Mao declared the atomic bomb program to be solely Chinese. In commemoration of the date of this “independence” (June 1959), the project was codenamed “596.” While on site, all project workers wore badges displaying the 596 emblem.

Despite Mao’s proclamation of scientific independence, however, Qian Sanqiang traveled to East Germany in July 1959 to meet with former Manhattan Project physicist—and Soviet spy—Klaus Fuchs. Fuchs and Qian spent the summer of 1959 going over detailed designs of the “Fat Man” plutonium implosion bomb. Unlike Fat Man, however, the first Chinese bombs used highly enriched uranium (HEU) from the Lanzhou facility; Chinese officials had shut down the uncompleted Jiuquan plutonium plant after the exodus of Soviet scientists from Beijing.

Despite Mao’s proclamation of scientific independence, however, Qian Sanqiang traveled to East Germany in July 1959 to meet with former Manhattan Project physicist—and Soviet spy—Klaus Fuchs. Fuchs and Qian spent the summer of 1959 going over detailed designs of the “Fat Man” plutonium implosion bomb. Unlike Fat Man, however, the first Chinese bombs used highly enriched uranium (HEU) from the Lanzhou facility; Chinese officials had shut down the uncompleted Jiuquan plutonium plant after the exodus of Soviet scientists from Beijing.

In 1961, there was some debate among Chinese officials over whether it was prudent to continue the nuclear program amid the failures of Mao’s Great Leap Forward. Mao, however, decided that the project must continue “even if the Chinese had to pawn their trousers” (105). On November 20, 1963, China conducted a “dry run”—a test without the HEU core—of its implosion device. The Lanzhou enrichment plant produced its first HEU in January 1964, and by the summer all materials were sent to the Lop Nur Nuclear Weapons Test Base for assembly.

On October 16, 1964, China successfully tested its first atomic bomb. The uranium implosion device exploded with 22 kilotons of force atop a 330 foot steel tower. As with the bomb project in general, the test was codenamed “596,” although United States intelligence also referred to it as “CHIC-1.” Shortly after the test, an official Chinese government statement affirmed, “This is a major achievement of the Chinese people in their struggle to increase their national defense capability and oppose the U.S. imperialist policy of nuclear blackmail and nuclear threats.” China also became the first country to declare a “no first use” policy: “The Chinese Government hereby solemnly declares that China will never at any time and under any circumstances be the first to use nuclear weapons.”

Ballistic Missiles and H-bombs

China began work on ballistic missile technology in 1955, when physicist Qian Xuesen (of no relation to Qian Sangiang) returned from the United States. Trained at MIT and Caltech, Qian had been a colonel in the United States Army and was charged with interrogating Nazi rocket scientists after World War II. Upon his return to China, Qian was put in charge of the missile and space program known as the Fifth Academy.

On October 25, 1966, China tested its first nuclear missile. As Marshal Nie Rongzhen recalled, “After the launch, I went to the atom bomb test base to see the results of the explosion at the designated target. The missile was deadly accurate. I was proud of our country, which had long been backward but now had its own sophisticated weapons.”

Beginning in 1960, Chinese scientists also began to develop thermonuclear weapons. Once again, the Chinese nuclear program likely benefited from Klaus Fuchs, who passed his rudimentary knowledge of the hydrogen bomb to Qian Sangiang when they met in 1959. China tested its first H-bomb bomb on June 17, 1967, with a force of 3.3 megatons. China acquired thermonuclear weapons only 32 months after its first atomic bomb test, much faster than the United States (over 7 years after its first test) and the Soviet Union (almost 4 years after its first test) took to build their respective hydrogen bombs.

Meanwhile, work resumed on the previously abandoned Jiuquan plant, which produced its first weapons-grade plutonium in September 1968, giving Beijing multiple paths to build nuclear weapons. Although China never signed the Limited Test Ban Treaty, it nonetheless began to conduct underground nuclear tests in 1969, probably because they were more difficult for neighboring countries to detect. In total, China conducted 45 nuclear tests, all at Lop Nur, with the last one on July 29, 1996.

Legacy

After Mao’s death in 1976, Deng Xiaoping took power in China. Among Deng’s many reforms, the Chinese nuclear program became much more transparent, and proliferation to other countries was encouraged. American scientist Danny Stillman was allowed to visit some of the nuclear sites during the 1990s. On one visit, he was told that the CHIC-4—the bomb used in China’s fourth nuclear test—was designed simply enough so that “anybody could build [it]” (Reed and Stillman 231).

Chinese scientists passed the CHIC-4 bomb technology to Pakistan, and allegedly conducted a nuclear test for Pakistan at Lop Nur on May 26, 1990. Additionally, China sold intermediate range ballistic missiles (IRBMs)—albeit without nuclear warheads—to Saudi Arabia, sold missile components to Iraq, and trained Libyan nuclear experts in Beijing. China has also tolerated the North Korean nuclear weapons program; after Pyongyang’s first test in 2006, China’s ambassador to the UN affirmed that “China does not approve of inspecting cargo to and from the D.P.R.K.” (328).

China acceded to the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) in 1992, entering the agreement as a nuclear weapon state (NWS) along with the four other members of the UN Security Council (the United States, Russia, the United Kingdom, and France). Beijing also joined the Nuclear Suppliers Group (NSG) in 2004, which limits the export of nuclear materials to countries who support non-proliferation. Today, China has approximately 260 nuclear warheads, including 50-60 ICBMs and four nuclear submarines.