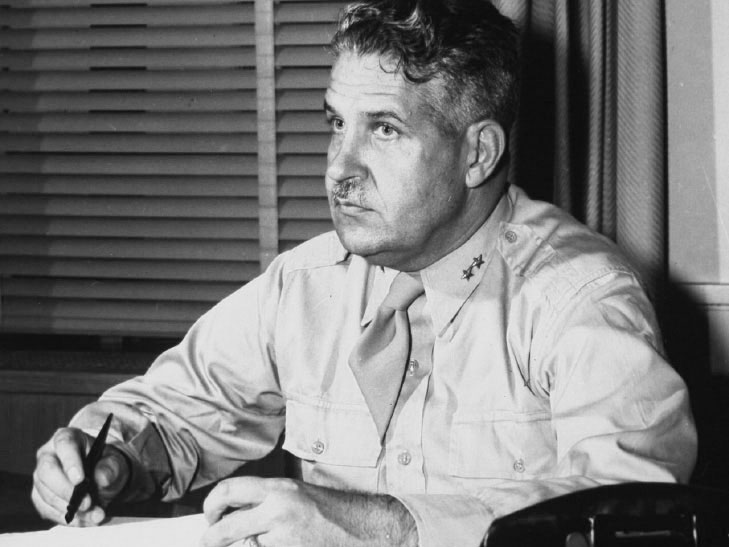

The Combined Development Trust (CDT) was an effort spearheaded by General Leslie Groves to control the world market of uranium ore. His goal was to both ensure a supply of raw material for the Manhattan Project and prevent nuclear proliferation overseas – especially in the Soviet Union.

Murray Hill

Groves first had to ascertain what exactly the world supply of uranium ore was. He launched a secret intelligence program code-named the Murray Hill Area Project. Project employees reviewed tens of thousands of documents, most in foreign languages, about locations of uranium ore. Groves dispatched geologists to oil fields all over the world and compiled information on more than fifty countries. Through the CDT, Groves would apply this intelligence to lock down as much of the supply as possible. Purchasing mineral rights and running intelligence was extremely costly; to avoid congressional oversight and keep the money secret, the Manhattan Project transferred tens of millions of funds directly to Groves’ personal bank account. Groves then channeled these funds to Murray Hill and the CDT’s purchasing program.

Creating the CDT

While Murray Hill was carrying out a massive intelligence operation, Groves looked to recruit allies to help deny the Soviet Union (and other countries) uranium ore. The U.S. and U.K. formed the Combined Development Trust (CDT) in 1944 and began buying up mineral rights to uranium and thorium ore around the world (Thorium can be transmuted to U-233, a fissionable isotope of uranium). In 1945, the CDT convinced the Belgian government to grant exclusive rights for the output of the Congolese Shinkolobwe mine. The same year, the Brazilian and Dutch governments agreed to protect their uranium and thorium supplies from the Soviet Union. In late 1945, Groves reported to Secretary of War Robert Patterson that CDT countries controlled 97% of worldwide uranium ore and 65% of thorium ore. The Soviet Union may have been able to acquire some through mines in Czechoslovakia, but Groves was determined to deny it access through all other means.

Soviet Comeback

Though the workings of Murray Hill and the CDT were top-secret, Stalin was privy to some of their information through espionage. Donald Maclean, First Secretary at the British Embassy in Washington from 1944 to 1948, had been working as a KGB agent since 1932. It was news to no one in Soviet leadership, however, that the Communist bloc was low on uranium ore reserves.

Soviet geologists were dispatched all over the ill-prospected empire. Tajikistan and Kazakhstan had promising deposits, but these were so isolated that satisfactory infrastructure would take years to build. Deposits in Russia also required construction before they could be mined; most initial uranium ore came from East Germany and Czechoslovakia. Meanwhile, extraction projects within the USSR required massive investment. By 1948, enough was being mined to sustain industrial-scale enrichment. This difficulty to acquire uranium ore contrasts with the Manhattan Project’s serendipitous purchase from Edgar Sengier. Still, in a few years the Soviet nuclear program had all the uranium ore it needed to develop nuclear weapons.

Neither Groves nor anyone in the Allied bloc had a good idea of what quantities of uranium ore the USSR was managing to extract and refine. The first Soviet nuclear test, coming the very next year, shocked Groves and many other Americans.