For the 50th anniversary of the end of World War II, the National Air and Space Museum (NASM) proposed an exhibition that would include displaying the Enola Gay, the B-29 Superfortress that was used to drop the bomb on Hiroshima. A fiery controversy ensued that demonstrated the competing historical narratives regarding the decision to drop the bomb.

Enola Gay, after the war

Following World War II, the Enola Gay had been moved around from location to location. Notably, from 1953 to 1960, its home was Andrews Air Force Base in Maryland. There its wings began to rust and vandals even damaged the plane. In 1961, the Enola Gay was fully disassembled and moved to the Paul E. Garber Preservation, Restoration and Storage facility for NASM.

In the 1980s, members of the 509th Composite Group asked for a proper restoration of the aircraft. Their motivations, at this time, stemmed primarily from the poor condition of the aircraft. The veterans formed “the Committee for the Restoration and Proud Display of the Enola Gay” to raise funds. Restoration efforts by the Smithsonian started on December 5, 1984. However, the museum felt “ambivalence about the plane’s eventual display,” described historian Edward T. Linenthal, who was on the advisory board of the Enola Gay exhibit.

Proposed Exhibition

In 1987, NASM hired Martin Harwit as their new director. His vision for the museum diverged from previous directors. He wanted the museum to be a “public conscience” that would discuss topics “under public debate,” Linenthal described. This vision included his conscious decision to display the Enola Gay.

In 1987, NASM hired Martin Harwit as their new director. His vision for the museum diverged from previous directors. He wanted the museum to be a “public conscience” that would discuss topics “under public debate,” Linenthal described. This vision included his conscious decision to display the Enola Gay.

At first, the Enola Gay was planned to be displayed at an annex NASM facility near Washington Dulles International Airport. In 1977, NASM had begun discussing the need for bigger buildings to house larger modern aircrafts, and in 1980, the museum had surveyed candidates for the future annex and decided upon the Dulles Airport. This proposed annex would solve the hassle of disassemble and reassemble larger aircrafts. The Enola Gay had recently finished being renovated and the museum had been concerned about transportation and reassemble fees; therefore, the proposed annex appeared to be a fitting location. They decided to exhibit the Enola Gay at the annex, with an accompanying message about the dangers of strategic bombing and escalation.

This proposal, however, was met with some opposition in the Research Advisory Committee’s meeting on October 1988. Committee member Admiral Noel Gayler believed that any exhibition of the Enola Gay would imply “that we are celebrating the first and so far the only use of nuclear weapons against human beings.” Heeding this warning, the committee tabled the discussion and decided to first test the waters with a sixteen-month series of talks, panels, and exhibits on “Strategic Bombings in World War II.” Meanwhile the proposed annex did not receive necessary funding until 1999, from a private donation.

At the same time, Harwit continued with his new vision for NASM with exhibitions such as “Legend, Memory and the Great War in the Air,” which was designed to clarify the myths that had arisen regarding World War I. This exhibition created some discomfort, with editors of the Wall Street Journal calling the curators “revisionist social scientists” and John T. Correll, editor of the Air Force Magazine, calling the exhibit a “strident attack on airpower in World War I” by characterizing the military aircraft as “instrument of death.” Still, Harwit pushed for a follow-up with an exhibition on World War II that would include the Enola Gay.

In December 1991, the potential for controversy of such an exhibit on WWII weighed heavily on the NASM advisory board. While they were “unanimous in agreeing that the Enola Gay is an artifact of pivotal significance and that it should be exhibited,” they asked the museum to avoid discussing the decision to drop the bomb and to consider an alternative site, such as an armed services museum.

Tom Crouch, chairman of the museum’s Aeronautics department, and lead curator Michael Neufeld led the team in charge of the exhibition. Taking these considerations in mind, they shifted the focus of the exhibition multiple times, before finally deciding on “The Crossroads: The End of World War II, the Atomic Bomb and the Origins of the Cold War.” They also began discussions with Japan about borrowing artifacts from Hiroshima and Nagasaki to be included in the exhibit in order to present a balanced narrative.

The team completed the museum’s first script on January 1994. The script was more than three hundred pages of texts and illustrations divided into five sections: “Fight to the Finish,” “Decision to Drop the Bomb,” “Delivering the Bomb,” “Ground Zero,” and “Legacy of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.”

“Death by a thousand cuts”

In 1993, executive director of the Air Force Association (AFA) Monroe W. Hatch Jr. sent a letter to Harwit, expressing concerns that the exhibition did not present an “accurate” portrayal of the war. He argued the proposed exhibition “treats Japan and the United States…as if their participation in the war were morally equivalent. If anything, incredibly, it gives the benefit of opinion to Japan, which was the aggressor…Japanese aggression and atrocities seem to have no significant place in this account.”

Initially, the NASM held a meeting with the AFA to discuss this concern; however, they could not reach a compromise. The NASM found the AFA’s position to be too extreme, and the AFA felt the NASM was deaf to their criticisms, said Linethal. This marked the beginning of the AFA’s formidable campaign against the exhibition.

For a detailed timeline of the controversy, see here and here.

Veterans and military groups, such as the American Legion, also began voicing their dissent. They felt that the exhibition dishonored veterans by discussing the controversy over the decision to drop the bomb and displaying graphic photos of atomic bomb victims. The Senate also unanimously proclaimed the script as “revisionist and offensive to many World War II veterans.” Interestingly, the Senate criticisms contradicted the AFA, who had acknowledged the proposed exhibition treated the men of the 509th with respect.

In response, Harwit wrote in an August 7, 1994 editorial in the Washington Post, “We want to honor the veterans who risked their lives and those who made the ultimate sacrifice…But we also must address the broader questions that concern subsequent generations—not with a view to criticizing or apologizing or displaying undue compassion for those on the ground that day, as some may fear, but to deliver an accurate portrayal that conveys the reality of the atomic war and its consequences.”

But the unrelenting media attacks and criticisms led Harwit to consult military historians, and on their recommendations, the museum produced a revised script. During the revision process, the section on the legacy of the bomb shrank dramatically, which angered Japan. Photographs of bomb victims as well as the artifacts from the bombing were largely removed from the exhibition, despite originally having been used to create a “balanced” narrative. The section on Japanese wartime atrocities was expanded.

These revisions, however, did not fully satisfy the opposing groups and sparked a new wave of criticism. Other groups asked for reinstallation of certain elements, including the photographs of Japanese victims, signing a statement that called the “historical cleansing” of the script as “unconscionable” and urged the Smithsonian to resist pressure to write “patriotically correct” history.

Ultimately, the script would be revised up to five times. But as one NASM curator accurately summarized it, at this point, the exhibition had been condemned to “death by a thousand cuts.”

Replacements and Resolutions

On January 30, 1995, Smithsonian Secretary Michael Heyman announced the decision to replace the exhibition with a smaller display and made the following statement:

“We made a basic error in attempting to couple an historical treatment of the use of atomic weapons with the 50th anniversary commemoration of the end of the war,” Heyman said. “In this important anniversary year, veterans and their families were expecting, and rightly so, that the nation would honor and commemorate their valor and sacrifice. They were not looking for analysis, and, frankly, we did not give enough thought to the intense feelings such an analysis would evoke.”

On May 2, Harwit resigned. He said, “I believe that nothing less than my stepping down from the directorship will satisfy the Museum’s critics and allow the Museum to move forward.” He later wrote a book on the controversial exhibition.

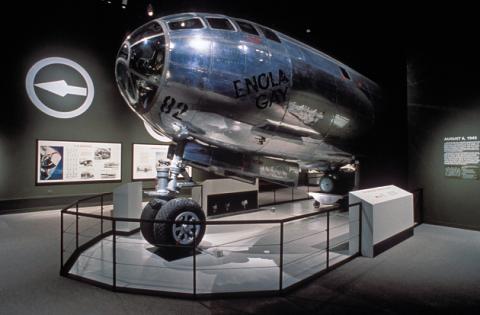

The planned exhibition was replaced by a simple display of the fuselage of Enola Gay with little historical context. It was accompanied by a video presentation that included interviews with the crew before and after the mission. The text describing the display was limited to the history and development of the Boeing B-29 fleet. The other part of the exhibition described restoration efforts.

While the simplification of the exhibit was intended to quiet most of the criticism, especially those of the American Legion, the final exhibit did not satisfy everyone. Numerous historians and scholars, many from the “revisionist” side of the debate over the use of the atomic bombs, protested the exhibit in a letter to the Secretary of the Smithsonian on July 31, 1995.

Meanwhile, the artifacts on loan from Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the graphic photos of victims were relocated to the American University Museum. This exhibition opened on July 9, 1995 with minimal protests. It was entitled “Constructing a Peaceful World: Beyond Hiroshima and Nagasaki” and was meant as a complement to a summer curriculum on nuclear war. Officials from the University stated it was not intended as a replacement for the Enola Gay exhibition at the Smithsonian.

Phil Budahn, a spokesman for the American Legion, stated in a New York Times article, “The Smithsonian is a Federal agency supported by taxpayer money, and rightly or wrongly, what it portrays is seen as the United States version of history. At American University, those constraints don’t apply.”

The exhibition of the fuselage ran from January 1995 to May 1998. Despite all the controversies, this exhibit drew more than a million visits in its first year alone, and a total of nearly four million visitors by the time it closed. It would be one of the most popular special exhibitions in the history of the Air and Space Museum.

Enola Gay Today

In 2003, the Smithsonian announced the opening of the annex NASM facility, the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center. Located near Dulles Airport, it provides a permanent home for Enola Gay, as originally proposed back in 1988. In its two hangars, the Center displayed 80 aircraft on opening day, and today it holds 170. In its first two weeks, the Center had more than 200,000 visitors. It now averages one million visitors per year and is the most-visited museum in Virginia.

In 2003, the Smithsonian announced the opening of the annex NASM facility, the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center. Located near Dulles Airport, it provides a permanent home for Enola Gay, as originally proposed back in 1988. In its two hangars, the Center displayed 80 aircraft on opening day, and today it holds 170. In its first two weeks, the Center had more than 200,000 visitors. It now averages one million visitors per year and is the most-visited museum in Virginia.

The 2003 exhibition of Enola Gay, following its trend of controversy, also raised a new round of protests, from Japanese survivors and others. Two men were even arrested for throwing red paint, which dented the plane, during protests on opening day.

In comparison, Bockscar, the B-29 that dropped Fat Man on Nagasaki, had a quieter retirement. After a tour in combat in Korea, Bockscar was decommissioned and flown to the National Museum of the US Air Force on Sept. 26, 1961. This museum is located at the Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio and is owned by the United States Air Force. Nearby a sign describes it as “The aircraft that ended World War II.”