During the Cold War, the United States and the Soviet Union were largely prevented from engaging in direct combat with each other due to the fear of mutually assured destruction (MAD). In 1962, however, the Cuban Missile Crisis brought the world perilously close to nuclear war.

“Why not throw a hedgehog at Uncle Sam’s pants?”

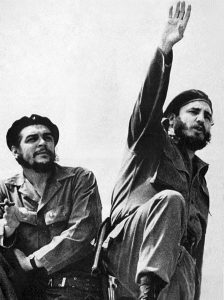

Soviet General Secretary Nikita Khrushchev’s decision to put nuclear missiles in Cuba was precipitated by two major developments. The first was the rise of the Cuban communist movement, which in 1959 overthrew President Fulgencio Batista and brought Fidel Castro to power. The Cuban Revolution was an affront to the United States, which took control of the island following the Spanish-American War of 1898. After granting Cuba its independence several years later, the United States remained a close ally. Under the directive of President Dwight D. Eisenhower, the CIA prepared to overthrow the Castro government. The resulting Bay of Pigs Invasion, ordered by President John F. Kennedy in April 1961, saw the defeat of approximately 1,500 American-trained Cuban exiles at the hands of the Cuban Revolutionary Armed Forces.

The Soviet Union, meanwhile, was motivated to assist the fledgling communist government that had somewhat surprisingly come to power without any support or influence from Moscow. Despite the Americans’ humiliating defeat at the Bay of Pigs, the Soviets feared that the United States would continue to oppose and delegitimize the Castro regime. As Khrushchev explained, “The fate of Cuba and the maintenance of Soviet prestige in that part of the world preoccupied me. We had to think up some way of confronting America with more than words. We had to establish a tangible and effective deterrent to American interference in the Caribbean. But what exactly? The logical answer was missiles” (Gaddis 76).

The other factor which led Khrushchev to his decision was the disparity between American and Soviet nuclear capabilities. According to physicist Pavel Podvig, Soviet bombers at the time “could deliver about 270 nuclear weapons to U.S. territory.” By contrast, the United States had thousands of warheads that it could deliver via 1,576 Strategic Air Command bombers as well as 183 Atlas and Titan intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), 144 Polaris missiles via nine nuclear submarines, and ten newly-built Minuteman ICBMs (Rhodes 93).

The Soviets did not yet have a reliable source of ICBMs, but they did have effective medium-range ballistic missiles (MRBMs) and intermediate-range ballistic missiles (IRBMs). If these weapons were deployed in Cuba, only 90 miles from the American mainland, it would in the eyes of Khrushchev equalize “what the West likes to call the ‘balance of power’” (Sheehan 438). From the Soviet perspective, nuclearizing Cuba would also serve as an effective response to the American Jupiter missiles deployed in Turkey. “Why not throw a hedgehog at Uncle Sam’s pants?” quipped Khrushchev at a meeting in April 1962 (Gaddis 75).

Operation Anadyr

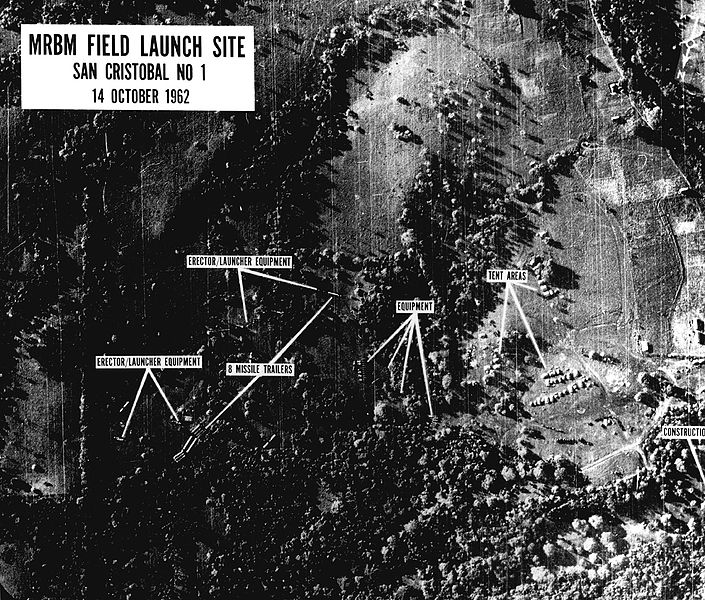

In May 1962, a special Soviet delegation made a secret trip to Cuba to work out the details of the operation—codenamed “Anadyr”—with Castro. (Marshal Sergei Biryuzov, a member of the delegation, naively suggested that the missiles could be disguised as palm trees—in reality, missile sites are very hard to conceal.) The Soviets planned to deploy two types of missiles: the R-12, whose range of 1,292 miles could hit as far north as New York or as far west as Dallas, and the R-14, which had a larger range of 2,500 miles, making most of the United States a potential target. Only the R-12 would ever make it to Cuba.

In May 1962, a special Soviet delegation made a secret trip to Cuba to work out the details of the operation—codenamed “Anadyr”—with Castro. (Marshal Sergei Biryuzov, a member of the delegation, naively suggested that the missiles could be disguised as palm trees—in reality, missile sites are very hard to conceal.) The Soviets planned to deploy two types of missiles: the R-12, whose range of 1,292 miles could hit as far north as New York or as far west as Dallas, and the R-14, which had a larger range of 2,500 miles, making most of the United States a potential target. Only the R-12 would ever make it to Cuba.

From July to October 1962, the Soviets secretly transported troops and equipment to Cuba. If all went according to plan, the Americans would find out about the operation only after it was too late to stop it. 41,902 soldiers were deployed—most wearing civilian clothes and introduced to an unconvinced Cuban population as “agricultural specialists”—before the crisis started. Thirty-six R-12 missiles and twenty-four launchers were successfully deployed on the island as well as a number of tactical cruise missiles designed to stop an invading American force (Sheehan 441). After the end of the Cold War, Russian officials revealed that 162 nuclear weapons were stationed in Cuba when the crisis broke out (Rhodes 99).

The CIA was unaware of the operation until October, as it had little presence in Cuba following the Bay of Pigs fiasco. Furthermore, a series of international incidents involving U-2 spy planes had caused the United States to put a five-week moratorium on aerial reconnaissance over Cuba. The missions resumed on October 14, when Air Force Major Richard Heyser flew over the island and recorded video evidence of the R-12 sites. Coupled with information from Colonel Oleg Penkovsky, a CIA spy in the Soviet Military Intelligence, there was no denying the harsh truth: the Soviet Union was deploying missiles in Cuba.

Quarantining Nuclear Missiles

With Soviet missiles on their way to Cuba, President Kennedy faced a pressing decision. In a briefing on October 17, CIA Director John A. McCone outlined three options: 1) “Do nothing and live with the situation,” 2) “Resort to an all-out blockade which would probably require a declaration of war and to be effective would mean the interruption of all incoming shipping,” or 3) “Military action,” which in turn had a number of possibilities ranging from targeted strikes on missile sites to an all-out invasion of the island (Hanhimaki and Westad 484).

With Soviet missiles on their way to Cuba, President Kennedy faced a pressing decision. In a briefing on October 17, CIA Director John A. McCone outlined three options: 1) “Do nothing and live with the situation,” 2) “Resort to an all-out blockade which would probably require a declaration of war and to be effective would mean the interruption of all incoming shipping,” or 3) “Military action,” which in turn had a number of possibilities ranging from targeted strikes on missile sites to an all-out invasion of the island (Hanhimaki and Westad 484).

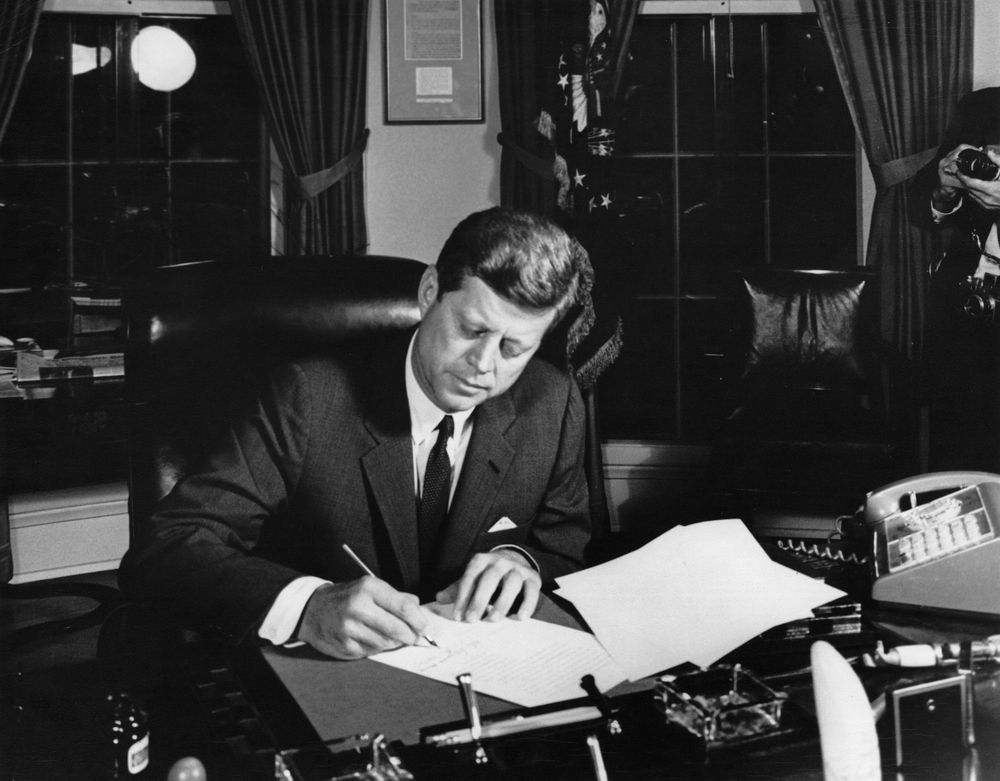

Kennedy wisely ruled out a military strike, noting that it was likely to miss at least some of the missiles and would prompt Soviet retaliation, probably against a vulnerable West Berlin. He ultimately chose the second option proposed by the CIA, but with one crucial difference. Rather than publicly calling it a “blockade,” which as McCone noted would have required a declaration of war, Kennedy instead termed it a “quarantine.” His military advisers nevertheless continued to push for an attack, to which Kennedy sardonically quipped, “These brass hats have one great advantage in their favor. If we listen to them, and do what they want us to do, none of us will be alive later to tell them that they were wrong” (Sheehan 445). Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara later affirmed that an American invasion would have prompted Soviet forces in Cuba “to use their nuclear weapons rather than lose them” (Rhodes 100).

Kennedy announced the blockade on October 22 in a speech that evoked the Monroe Doctrine, a nineteenth century policy which established the United States’ sphere of influence in the Western Hemisphere by opposing any future European colonization in the Americas: “It shall be the policy of this nation to regard any nuclear missile launched from Cuba against any nation in the Western Hemisphere as an attack by the Soviet Union on the United States, requiring a full retaliatory response upon the Soviet Union.” Kennedy also ordered the Strategic Air Command (SAC) into Defense Condition 3 (DEFCON 3) and two days later upped it to DEFCON 2, only one step short of nuclear war. Among other preparations, 66 B-52s carrying hydrogen bombs were constantly airborne, replaced with a fresh crew every 24 hours.

The gambit was designed to exert maximum pressure on the Soviet Union. U.S. officials made sure that the Soviets would pick up the communications ordering the American nuclear forces on high alert. At the United Nations, American Ambassador Adlai Stevenson famously sparred with Soviet Ambassador Valerian Zorin over the crisis. “Well, let me say something to you, Mr. Ambassador—we do have the evidence [of missile sites],” asserted Stevenson. “We have it, and it is clear and it is incontrovertible. And let me say something else—those weapons must be taken out of Cuba” (Hanhimaki and Westad 485).

The B-59 Submarine

Perhaps the most dangerous moment of the Cuban Missile Crisis came on October 27, when U.S. Navy warships enforcing the blockade attempted to surface the Soviet B-59 submarine. It was one of four submarines sent from the Soviet Union to Cuba, all of which were detected and three of which were eventually forced to surface. The diesel-powered B-59 had lost contact with Moscow for several days, and thus was not informed of the escalating crisis. With its air conditioning broken and battery failing, temperatures inside the submarine were above 100ºF. Crew members fainted from heat exhaustion and rising carbon dioxide levels.

American warships tracking the submarine dropped depth charges on either side of the B-59 as a warning. The crew, unaware of the blockade, thought that perhaps war had been declared. Vadim Orlov, an intelligence officer aboard the submarine, recalled how the American ships “surrounded us and started to tighten the circle, practicing attacks and dropping depth charges. They exploded right next to the hull. It felt like you were sitting in a metal barrel, which somebody is constantly blasting with a sledgehammer.”

Unbeknownst to the Americans, the B-59 was equipped with a T-5 nuclear-tipped torpedo. It was capable of a blast equivalent to 10 kilotons of TNT, roughly two-thirds the strength of the bomb dropped on Hiroshima. Firing without a direct order from Moscow, however, required the consent of all three senior officers on board. Orlov remembered Captain Valentin Savitsky shouting, “We’re going to blast them now! We will die, but we will sink them all—we will not disgrace our Navy!” Political officer Ivan Semonovich Maslennikov agreed that they should launch the torpedo.

The last remaining officer, Second Captain Vasili Alexandrovich Arkhipov, dissented. They did not know for sure that the ship was under attack, he argued. Why not surface and then await orders from Moscow? In the end, Arkhipov’s view prevailed. The B-59 surfaced near the American warships and the submarine set off north to return to the Soviet Union without incident.

Armageddon Averted

Although the Americans and the Soviets ultimately reached an agreement, it took almost a week of tense negotiations following the institution of the blockade. Meanwhile, the fate of the world continued to hang in the balance. On October 26, Khrushchev sent a private letter to Kennedy proposing a resolution to the crisis: “We, for our part, will declare that our ships, bound for Cuba, will not carry any kind of armaments. You would declare that the United States will not invade Cuba with its forces and will not support any sort of forces which might intend to carry out an invasion of Cuba. Then the necessity for the presence of our military specialists in Cuba would disappear.” A deal was on the table—the Soviet Union would remove the missiles if the United States was willing to accept Castro’s communist regime in Cuba.

On October 27, however, Khrushchev upped his demands in an address broadcast publicly via Radio Moscow. The Soviet Union would stand down in Cuba only if the United States agreed to remove the Jupiter missiles deployed in Turkey. Later that day, an American U-2 reconnaissance plane was shot down over Cuba. The pilot, Major Rudolf Anderson, would end up being the only military fatality during the crisis. American officials—mistakenly believing that the Kremlin had directly ordered the attack—were demoralized by the turn of events. Nuclear war seemed imminent.

On October 27, however, Khrushchev upped his demands in an address broadcast publicly via Radio Moscow. The Soviet Union would stand down in Cuba only if the United States agreed to remove the Jupiter missiles deployed in Turkey. Later that day, an American U-2 reconnaissance plane was shot down over Cuba. The pilot, Major Rudolf Anderson, would end up being the only military fatality during the crisis. American officials—mistakenly believing that the Kremlin had directly ordered the attack—were demoralized by the turn of events. Nuclear war seemed imminent.

Once again, Kennedy refused to retaliate. Unbeknownst to many of his advisors, the President instructed his brother, Attorney General Robert Kennedy, to meet secretly with Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin. The United States was willing remove the missiles from Turkey within five months, but under the condition that it not be part of any public resolution to the conflict. Given that Turkey was a member of NATO, an admission that the United States was trading missiles in Turkey to resolve the situation in Cuba would have undermined the alliance. The secret agreement was not revealed until decades later.

The next day, Khrushchev sent a letter to Kennedy agreeing to the terms and announced an effective end to the crisis on Radio Moscow: “The Soviet government, in addition to previously issued instructions on the cessation of further work at building sites for the weapons, has issued a new order on the dismantling of the weapons which you describe as ‘offensive,’ and their crating and return to the Soviet Union.” Kennedy hailed the decision as “an important and constructive contribution to peace” while warning of “the compelling necessity for ending the arms race and reducing world tensions.”

Aftermath

The Soviet Union began to dismantle the nuclear sites in Cuba within a day of the agreement. Fidel Castro—furious with Khrushchev’s decision to give in to American demands—refused to let in any U.N. inspectors to verify the removal of the missiles. The Soviets had to resort to loading missiles on ship decks and uncovering them at sea, where they could be photographed by American planes. The United States lifted the blockade on November 20 and removed the Jupiter missiles from Turkey by April 1963. In the end, however, the removal of the missiles was a fairly meaningless gesture as the new Minuteman ICBMs had rendered the Jupiters obsolete.

The shock of the Cuban Missile Crisis was a highly influential factor in the success of future arms control negotiations between the United States and the Soviet Union, such as the ban on atmospheric testing. As Khrushchev affirmed only days after the end of the crisis, “We fully agree with regard to three types of tests or, so to say, tests in three environments. This is banning of tests in atmosphere, in outer space and under water” (Hanhimaki and Westad 488). Less than a year later, the two superpowers signed the Limited Test Ban Treaty (LTBT), which included the principles outlined by Khrushchev. The Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) followed in 1968.

Nevertheless, the years after the crisis also saw a massive increase in the construction of nuclear weapons in the Soviet Union. The Soviet stockpile tripled by the end of the decade and peaked at over 40,000 warheads during the 1980s. This phenomenon can be explained in part by the fact that Soviet leaders felt they had little choice but to capitulate during the crisis given the comparative weakness of their nuclear arsenal. As Soviet lieutenant general Nikolai Detinov explained, “Because of the strategic [imbalance] between the United States and the Soviet Union, the Soviet Union had to accept everything that the United States dictated to it and this had a painful effect on our country and our government…. All our economic resources were mobilized [afterward] to solve this problem” (Rhodes 94).

The crisis also prompted the creation of the Moscow-Washington hotline, a direct telephone link between the Kremlin and the White House designed to prevent future escalations. Kennedy also ordered the creation of the nuclear “football” which would give him and future presidents the means to order a nuclear strike within minutes.