Health & Safety

On November 3, 1943, General Leslie Groves appointed Stafford Warren as chief of the MED’s medical section and medical advisor to the Manhattan Project. Warren’s initial task was to staff hospitals at Oak Ridge, Hanford, and Los Alamos to provide adequate medical care for each site’s rapidly growing workforce. After each site became fully operational, Warren’s medical section focused their efforts on medical research and were responsible for the MED’s health and safety programs. Warren would reiterate, however, that medicine was subservient to the larger goal of “winning the present war” and presented the medical research program as funded and directed to “strengthen government interests from a medico-legal point of view”.

To Warren and other MED officials, protecting workers from atomic energy hazards was important but did not merit unusual or excessive safety standards. He believed that the atomic weapons industry should be treated as simply another industrial program under which “normal industrial practices were good enough” and that special standards should apply only upon proof of prompt, clear-cut biological changes or health threats. As research has since proven, many of the fatal injuries in this field are never marked by “prompt, clear-cut biological changes,” but instead appear only after a lengthy latency. While District officials made efforts to reduce the amount of exposure workers received from radiation and other toxic chemicals, there was not enough done to protect against the long-term effects of increased exposure on an individual’s health.

At the Chicago Met Lab, scientists implemented the safeguards for plutonium work by putting linoleum on all the floors and having people use filter masks, rubber gloves, and outer protective clothing. Eating in the laboratories was not permitted, and Methods were developed to monitor the air in the labs for evidence of plutonium dust contamination. Similar safety procedures would be adopted at Los Alamos, Hanford, and Oak Ridge by the middle of 1944.

A procedure to detect the inhalation of plutonium dust using nose swabs was also introduced by 1944. The process involved a moist filter-paper swab which was inserted into the nostril and rotated, then the swab was spread out, dried, and read in an alpha detector. A reading of 100 counts per minute or higher was considered evidence of an exposure. Nose-swipe counts are still used for plutonium workers today and are part of the criteria used to decide when medical treatment for the worker, including prompt collection of urine samples, is necessary.

Safety Monitoring Equipment

Safety monitoring equipment was also developed and implemented throughout the course of the Manhattan Project. They were used to monitor radiation and radioactive exposure, and prevent large-scale accidents at the reactors.

Radiation Detectors

Radiation detectors were needed at Manhattan Project sites to delimit safe and dangerous areas and to monitor internal exposures to plutonium and other harmful radioisotopes. In the early stages of the Project, the Chicago Metallurgical Laboratory supplied the radiation detectors needed to monitor uranium and plutonium in the work environment. By 1944, however, a chronic shortage of radiation detectors lead at least one site, Los Alamos, to begin a detector development program of its own.

The program was led by Richard Watts of the Electronics Group in the Physics Division. Watts and his team developed a number of alpha-particle detectors–culminating in the portable “Pee Wee”–named for its mere nineteen pounds, to detect radioactivity in the work environment.

The work done by Watts would set the stage for later work. After the war, the Los Alamos Laboratory emerged as a leader in radiation detection technology, developing some very special radiation detectors for monitoring internal exposures to radioisotopes. Wright Langham, the leader of the Radiobiology Group of the Health Division, organized a group to produce detectors that not only provided radiation protection but also had a significant impact in the fields of biology and nuclear medicine.

Geiger-Müller Counter

The Geiger-Müller counter was first conceived by German physicist Hans Geiger in 1908 and fully developed in 1928 after Walther Müller (a PhD student of Geiger) developed the sealed Geiger-Müller tube which could detect more types of ionizing radiation, making the device a more practical radiation sensor. A Geiger counter detects the emission of nuclear radiation — alpha particles, beta particles, or gamma rays — by the ionization produced in a low-pressure gas in a Geiger–Müller tube.

The Geiger-Müller counter was first conceived by German physicist Hans Geiger in 1908 and fully developed in 1928 after Walther Müller (a PhD student of Geiger) developed the sealed Geiger-Müller tube which could detect more types of ionizing radiation, making the device a more practical radiation sensor. A Geiger counter detects the emission of nuclear radiation — alpha particles, beta particles, or gamma rays — by the ionization produced in a low-pressure gas in a Geiger–Müller tube.

The Geiger counter was the most reliable radiation detector used during the Manhattan Project, and it has been a popular instrument for use in radiation dosimetry, health physics, experimental physics, the nuclear industry, geological exploration and other fields, due to its robust sensing element and relatively low cost.

Despite their reliability, Geiger counters still have their limitations. Because the output pulse from a Geiger-Muller tube is always the same magnitude regardless of the energy of the incident radiation, the tube cannot differentiate between radiation types. Geiger counters are also unable to measure extremely high radiation rates due to the “dead time” of the tube. This is an insensitive period after each ionization of the gas during which any further incident radiation will not result in a count, and the indicated rate is therefore lower than actual.

Scintillation Counters

Scintillation counters also continued to develop during the course of the Manhattan Project. The technique was originally created in 1903 to detect alpha particles emitted by radium, and worked by counting the flashes of light produced when the alpha particles reacted with the zinc sulfide in the counter. But, the method fell into disuse by the 1930s because recording data was laborious and unreliable compared to the Geiger-Muller counters electronic output. The scintillator was revived with the development of the photomultiplier tube, an instrument that converts light into an electrical pulse. The innovation greatly improved the reliability of scintillation counters, allowing the number of counts could be recorded electronically. In addition, the discovery of a variety of new types of scintillators, liquid and solid, helped improve the rate of detection of alpha particles. Scintillation counting developed through the 1950s to produce the most versatile, sensitive, and reliable detectors of the time.

Liquid scintallation counters were another important innovation that were a marked improvement on existing techniques for the detection of tritium and other beta-emitting radioisotopes such as carbon-14 and phosphorus-32. Los Alamos scientists became involved in these developments as research on the hydrogen bomb began during the early 1950s.

Failsafes

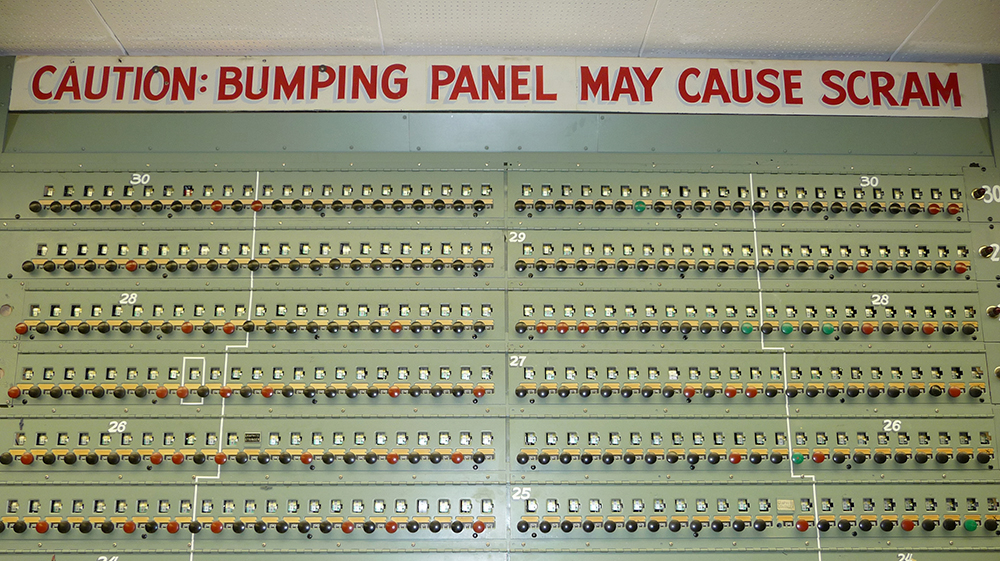

Reactors also needed to be monitored for the safety of the workers and surrounding communities. The B Reactor at Hanford had three different fail-safes to shut down the reactor to prevent a critical meltdown.

Reactors also needed to be monitored for the safety of the workers and surrounding communities. The B Reactor at Hanford had three different fail-safes to shut down the reactor to prevent a critical meltdown.

The first fail-safe, the SCRAM (Single Control Rod Axe Man) method, involved twenty-nine control rods with boron tips that hung from a rope above the reactor. If the reaction went out of control, the reactor operator would chop the rope and the rods would fall into the reactor and poison the reaction. The rope was soon replaced with an electric winch that could raise or lower the safety rods (but the acronym remained).

The second fail-safe method involved a boron solution acid that would be dumped into the reactor in the event that the safety control rods failed to descend into the reactor. The only problem with this method was that the solution, if used, would likely prevent the reactor from ever becoming operational again.

The boron solution acid was soon replaced with the Balls 3x system. This fail-safe involved tiny boron balls that could be dumped into the reactor to stop the reaction. This was a much more efficient method, because the balls could be retrieved and it did not permanently disable the reactor.