A key component of keeping the Manhattan Project secret was making sure Project sites were secret and secure. One obvious reason the Manhattan Engineers District selected Los Alamos, NM, Oak Ridge, TN, and Hanford, WA as project sites was their geographic isolation. Still, District officials took extraordinary measures to ensure that no one without the proper clearance was allowed access to site buildings or facilities. Each site had multiple security checkpoints that were guarded by military police twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week. In addition, tall barbed-wire fencing surrounded each site’s perimeter, preventing any intruders from gaining unwanted access to key buildings and deterring any employee from clandestinely sneaking out (perhaps with classified documents).

Security

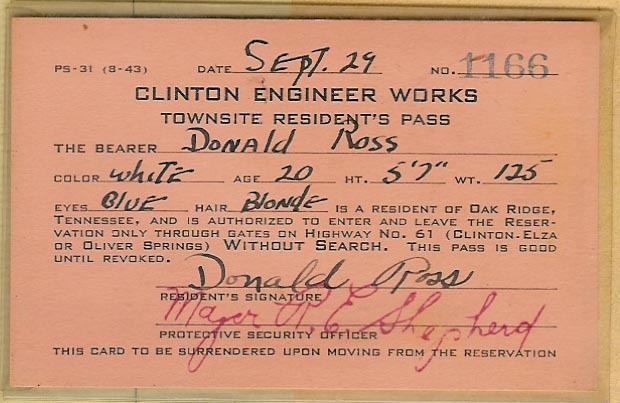

Each worker at the Manhattan Project underwent a rigorous background check conducted by the FBI to ensure that he or she had no criminal history or suspicious connections with Axis sympathizers. It could often take several weeks for prospective employees to get cleared, and sometimes the FBI would contact close relatives or previous employers to clarify any suspicions that might be raised during the process of their investigation. Every employee that worked at one of the Manhattan Project sites had a security badge that displayed their picture, their job position, and their level of clearance. An employee’s job usually determined their level of clearance. Construction workers, low-level engineers, and metallurgical workers usually had low-level clearance, which meant their work was highly compartmentalized and they were informed on a “need-to-know” basis. These workers were generally given red or blue badges, depending on their level. Top-level physicists, engineers, and important scientists usually had the highest clearance, and generally knew that the overall goal of the Manhattan Project was to build an atomic bomb. These workers were given white badges, which entitled them (at least those at Los Alamos) to sit in on lectures that Oppenheimer frequently delivered to discuss the project’s progress and address some of the key problems scientists faced.

In addition, mail coming in and going out of Los Alamos was meticulously censored. Security officials would inspect each and every individual piece of mail, making sure that any information regarding a site’s location, work activity, or technical details was removed. In some cases, military officials would follow up with civilians whose letters contained something unusually suspicious, such as coded puzzles or words. Richard Feynman, a brilliant theoretical physicist who worked at Los Alamos in Hans Bethe’s theoretical group, liked to send his wife coded puzzles in the mail. Security officials immediately began questioning him about the nature of the puzzles and requested that he discontinue using coded words in his letters home. Feynman, of course, would find other ways to annoy Los Alamos’ security guards. In many cases, parents simply wanted to know what their children were working on and why they had to be so secretive in their letters. Mail censorship frustrated everyone, but many Manhattan Project veterans would later  argue that it was essential for secrecy and security purposes.

argue that it was essential for secrecy and security purposes.

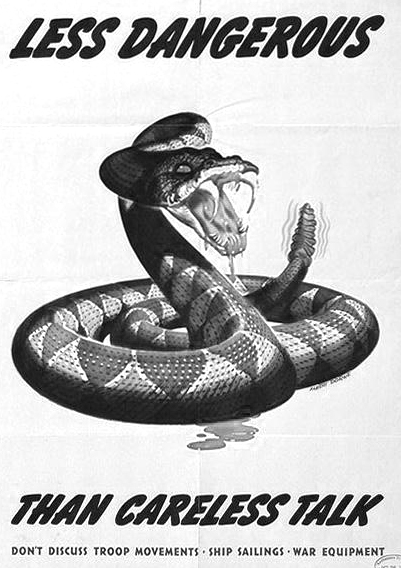

Every District worker, whether scientist or construction worker, had to sign a form pledging silence about the Manhattan Project. But for General Leslie Groves, forms were not enough. The MED’s security and intelligence agency accepted Groves’ fear that randomly dropped phrases, bits of knowledge, and names or places might fall into the hands of some centralized enemy spy network, where it might then enable reconstruction of the project. To counter such a nebulous possibility required vast expansion of the MED’s controls on the way people talked and wrote. As a result, the District would undertake a massive “propaganda” campaign to remind workers of proper attitude toward language and its most dangerous manifestation, “loose talk.”

Secrecy

_0.jpg)

The overriding concern of General Leslie R. Groves in managing the Manhattan Project was secrecy. Anyone who entered the grounds of the Los Alamos laboratory or one of the other “secret cities” had to have a purpose and a pass. At all the sites, signs and billboards admonished workers to protect the project’s secrets: “What you see here, what you do here, what you hear here, when you leave here, let it stay here!”

Scientists, used to the free exchange of ideas, rebelled against the compartmentalization. At Los Alamos, Oppenheimer insisted that weekly scientific colloquia and other exchanges were essential to solve difficult problems. But this openness among the top echelon of scientists at Los Alamos was an exception and was contained “inside the fence.” For everyone else, it was “Stick to your knitting!”

Secrecy Unveiled: The Manhattan Project Goes Public

News of the bombing of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945 stunned the world. Never before had a weapon of such destructive proportions been used upon an enemy population with such devastating effect.

News of the bombing of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945 stunned the world. Never before had a weapon of such destructive proportions been used upon an enemy population with such devastating effect.

Naturally, many ordinary Americans were curious. Newspapers across the United States and the world were filled with stories that speculated on the potential of this new, “atomic” technology. Many wondered how the United States had come to develop the world’s first nuclear weapon. How long did it take the government to develop this technology? Why was it kept secret? Who worked on the project? Where were the bombs built?

Gradually, reports of a $2 billion U.S. government war project, codenamed the “Manhattan Project,” were released. In anticipation of the bombings of Japan, General Leslie Groves had physicist Henry DeWolf Smyth prepare a report that was to be the official U.S. government history and statement about the development of the atomic bombs.

The Smyth Report was released to the public on August 12, 1945. Its release, only days after the bombing of Nagasaki, and the amount of information it disclosed about the just-revealed Manhattan Project made it a landmark document. The report outlined the development of the then-secret laboratories and production sites at Los Alamos, NM, Oak Ridge, TN, and Hanford, WA, and the basic physical processes responsible for the functioning of nuclear weapons, in particular nuclear fission and the nuclear chain reaction.

For more about the Smyth Report, click here.