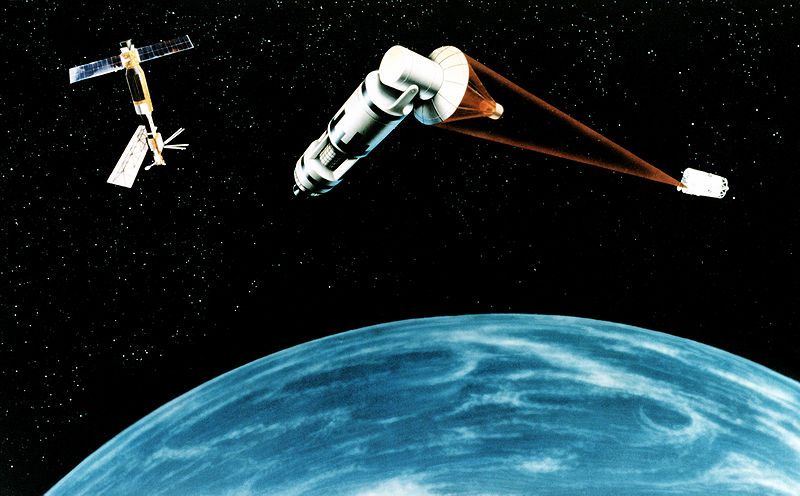

During the 1980s, President Ronald Reagan initiated the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), an anti-ballistic missile program that was designed to shoot down nuclear missiles in space. Otherwise known as “Star Wars,” SDI sought to create a space-based shield that would render nuclear missiles obsolete.

The Origins of SDI

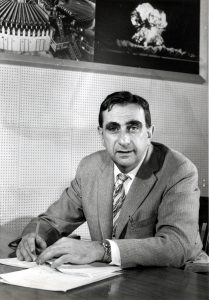

Reagan’s interest in anti-ballistic missile technology dated back to 1967 when, as governor of California, he paid a visit to physicist Edward Teller at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. Reagan reportedly was very taken by Teller’s briefing on directed-energy weapons (DEWs), such as lasers and microwaves. Teller argued that DEWs could potentially defend against a nuclear attack, characterizing them as the “third generation of nuclear weapons” after fission and thermonuclear weapons, respectively (Rhodes 179). According to George Shultz, the Secretary of State during Reagan’s presidency, the meeting with Teller was “the first gleam in Ronald Reagan’s eye of what later became the Strategic Defense Initiative” (Shultz 261). This account was also confirmed by Teller, who wrote, “Fifteen years later, I discovered that [Reagan] had been very interested in those ideas” (Teller 509).

The need for an effective anti-ballistic missile system grew considerably in Reagan’s eyes after he visited the headquarters of the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) in 1979. The NORAD headquarters are located deep inside the Cheyenne Mountain Complex, a military bunker near Colorado Springs. During his tour of the complex, Reagan—impressed with the extensive fortifications—asked General James Hill what would happen if a Soviet nuclear missile hit within the vicinity of the mountain. “It would blow us away,” said Hill. A missile could be tracked, but there was nothing they could do to stop it from reaching its target. “There must be something better than this,” replied a shocked Reagan (Shultz 262).

After his election in 1980, President Reagan demonstrated a continued interest in anti-ballistic missile technology from the early stages of his administration. In early 1981, he signed National Security Decision Directive (NSDD) 12, which included the creation of a “vigorous research and development program on ballistic missile defense systems.” Reagan also adopted tough anti-Soviet rhetoric and policy, a stark contrast to the decade of détente which preceded him. Three weeks before the announcement of SDI, Reagan gave his famous “evil empire” speech, which branded the Soviet Union as the unequivocal enemy of the United States. An anti-ballistic missile system—one which would give the United States complete protection from the Soviet Union—was the natural next step.

The Announcement

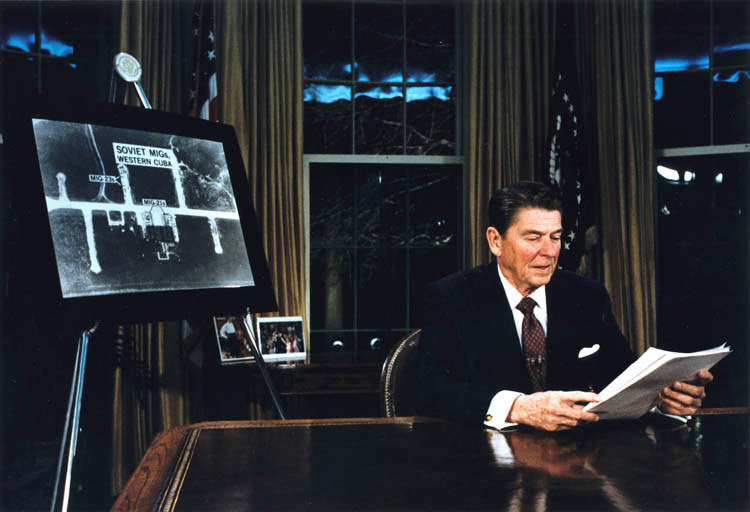

On March 23, 1983, President Reagan announced the SDI program in a television address broadcast nationally. “What if free people could live secure in the knowledge that their security did not rest upon the threat of instant U.S. retaliation to deter a Soviet attack, that we could intercept and destroy strategic ballistic missiles before they reached our own soil or that of our allies?” he said. “I call upon the scientific community in our country, those who gave us nuclear weapons, to turn their great talents now to the cause of mankind and world peace, to give us the means of rendering these nuclear weapons impotent and obsolete.”

Reagan instructed Secretary of State Shultz to give Soviet Ambassador to the U.S. Anatoly Dobrynin an advance copy of the speech announcing SDI. Shultz told Dobrynin “that this was a research and development effort” and “that we knew that the Soviets were pursuing such efforts as well, and that our proposed program for strategic defense would be designed to enhance stability.” A disturbed Dobrynin reportedly replied, “You will be opening a new phase in the arms race” (Shultz 256).

Reagan’s speech blindsided many of his close advisors, some of whom had not been given advance warning that SDI would soon be administration policy. Secretary of State Alexander Haig recalled, “I know the aftermath the next day in the Pentagon, where they were all rushing around saying, ‘What the hell is strategic defense?’” (O’Connell 23).

In an interview only a few days after the announcement, Reagan insisted that SDI was not part of a new arms race but instead a path to ridding the world of nuclear weapons altogether. To prove this point, the president suggested that the United States could eventually share SDI with the Soviet Union. “A President of the United States could offer to give that same defensive weapon to them to prove to them that there was no longer any need for keeping these missiles,” explained Reagan. “Or with that defense, he could then say to them, ‘I am willing to do away with all my missiles. You do away with yours’” (Shultz 260).

Reaction in the West

The announcement of SDI shocked officials around the globe. To many, it was as unexpected as it was provocative. As Secretary of State Schultz explained, “Prior to the president’s speech, even the possibility that the United States might seriously seek to defend itself from nuclear attack seemed outlandish. After President Reagan’s speech, what had seemed ‘outlandish’ became the agenda for debate” (Shultz 261).

Among other controversies, SDI threatened to undermine the American and Soviet deterrence policy of mutually assured destruction (MAD). Decades before, the two superpowers had successfully developed intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) as well as effective second strike capabilities such as nuclear submarines. These weapons would be very difficult to destroy, even in a preemptive nuclear strike, and thus the Americans and the Soviets reached a certain equilibrium. Neither country could attack the other without the strong probability that both sides would be annihilated.

MAD was firmly instituted as the policy of nuclear deterrence for both sides when President Richard Nixon and General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev signed the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty (ABM) in 1972. The treaty limited each side “to have one limited ABM system to protect its capital and another to protect an ICBM launch area,” and the signatories agreed “not to develop, test, or deploy [additional] ABM launchers.” ABM recognized the reality that an anti-ballistic missile system would actually make both sides less secure because it would undermine the balance of mutually assured destruction.

Unsurprisingly, concerns over MAD and ABM were widespread following the announcement of SDI, even among members of the Reagan administration. “Can you be sure of an impenetrable shield?” asked Shultz. “And what about cruise missiles? What about stealth bombers? What about the ABM Treaty? What about our allies and the strategic doctrine on which we and they depend?” (Shultz 250). Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs Lawrence Eagleburger likewise critiqued, “The president seems to be proposing an updated version of the Maginot Line [the interwar defensive fortifications on the Franco-German border which gave France a false sense of security]” (252).

Another common criticism of SDI was that it was simply not a feasible project. For example, the day after Reagan announced SDI, Senator Ted Kennedy dismissed his speech as “misleading Red-scare tactics and reckless Star Wars schemes,” indirectly coining SDI’s Hollywood nickname. A New York Times op-ed similarly noted, “It remains a pipe dream, a projection of fantasy into policy….There’s no statesmanship in science fiction.”

Scientists also expressed their doubts about SDI. In 1985, for example, physicist Wolfgang Panofsky wrote in Physics Today, “ABM defense technology deserves further research within treaty limits, but the ‘Star Wars’ program is too large, too political, raises false hopes and poses grave dangers to national and world security.” Members of the Reagan administration, however, pushed back against this notion. Science Advisor George Keyworth argued, “I have been asked time and time again one simple question, is it now a good time to attempt a development of a technological solution to making ballistic missiles obsolete? No more, no less. And the answer, to the best of my judgment, is yes. It is technically feasible.”

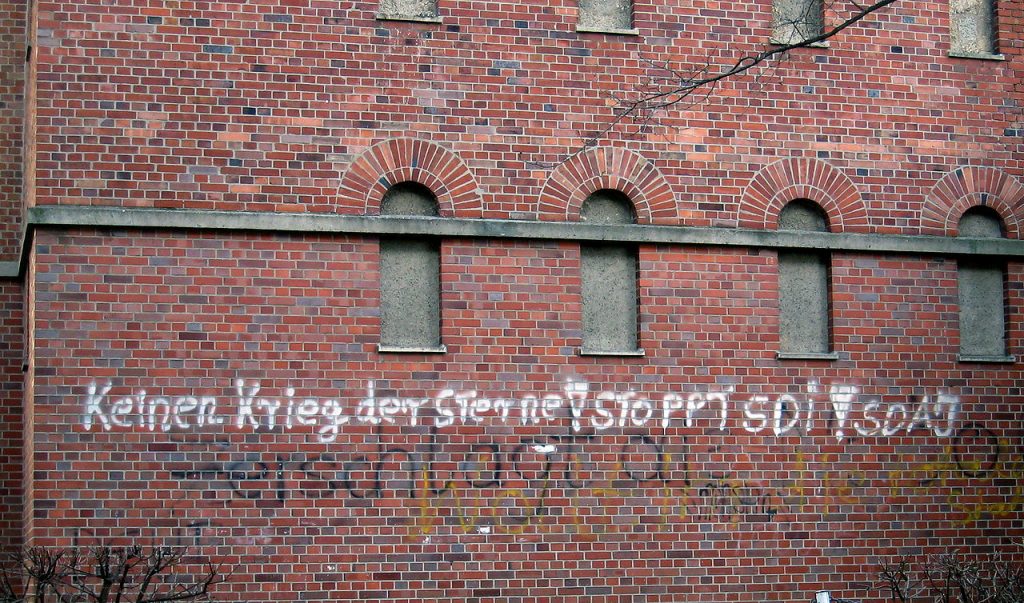

Allies of the United States in Europe, particularly those in NATO, were also alarmed by the development of SDI. Throughout most of the Cold War, American nuclear power was the primary deterrent which prevented a Soviet invasion of Western Europe. With SDI, the Europeans feared that the United States would no longer provide this defense. As U.S. Ambassador to Canada Thomas Niles explained, “The Europeans saw SDI as an indication that the United States, at least theoretically, was interested in backing away from this commitment to Europe and building a ‘Fortress America,’ with this high-tech system that would protect us, but not them.”

Allies of the United States in Europe, particularly those in NATO, were also alarmed by the development of SDI. Throughout most of the Cold War, American nuclear power was the primary deterrent which prevented a Soviet invasion of Western Europe. With SDI, the Europeans feared that the United States would no longer provide this defense. As U.S. Ambassador to Canada Thomas Niles explained, “The Europeans saw SDI as an indication that the United States, at least theoretically, was interested in backing away from this commitment to Europe and building a ‘Fortress America,’ with this high-tech system that would protect us, but not them.”

French President Francois Mitterrand, for example, was very vocal about his concerns regarding SDI: “I am opposed to the idea of SDI—I perceive it as a potential opportunity for a first strike….It is obvious that SDI will not replace nuclear weapons, but will become a substantial addition to the existing arsenals” (Gorbachev 429). Although they protested the development of SDI, the opposition of the United States’ European allies had little effect on the program’s development.

Despite its many critics, the Strategic Defense Initiative was ultimately very popular with the American public. It appealed both to the desire for security against nuclear war and to the belief in the superiority of American technological achievements. Political scientist Kerry L. Hunter explained this phenomenon:

The power of Reagan’s Star Wars vision…lay in its utopian characteristics. It did not matter that Star Wars ignored reality. In fact, it was for this reason that the ideal was so appealing. The Star Wars dream allowed Americans to avoid a very stark truth that was practically intolerable to face: there was nothing they could do to protect themselves from nuclear annihilation outside of cooperating with the Soviets (Rhodes 180).

Polling data from the 1980s supports this notion. A 1985 Gallup poll reported that 61% of respondents replied affirmatively to the question, “Would you like to see the United States go ahead with the development of (SDI), or not?”

Development

Two days after announcing SDI, Reagan signed NSDD 85, which authorized “the development of an intensive effort to define a long term research and development program aimed at an ultimate goal of eliminating the threat posed by nuclear ballistic missiles,” but “in a manner consistent with our obligations under the ABM Treaty and recognizing the need for close consultations with our allies.” According to the Reagan administration, SDI was not a violation of ABM because it was only pursuing research and development, not deployment. As Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger explained, “The fact is, deployment will not occur unless a defensive system is developed that would better contribute in better ways to deterrence than the arrangement which now keeps the peace, as it has for nearly 40 years” (O’Connell 77).

Although he was influenced by scientists such as Teller, the Strategic Defense Initiative was ultimately Reagan’s personal vision because it was based on technology that had not yet been invented. Scientific experts had not made any groundbreaking discoveries in the years leading up to the announcement of SDI, and they were far from certain whether such a system was even possible. Scientific development did not influence policy in this case; it was policy that was intended to influence science. Reagan confirmed this fact in a 1984 letter: “Frankly, I have no idea what the nature of such a defense might be. I simply asked our scientists to explore the possibility of developing such a defense” (Lazzari 31).

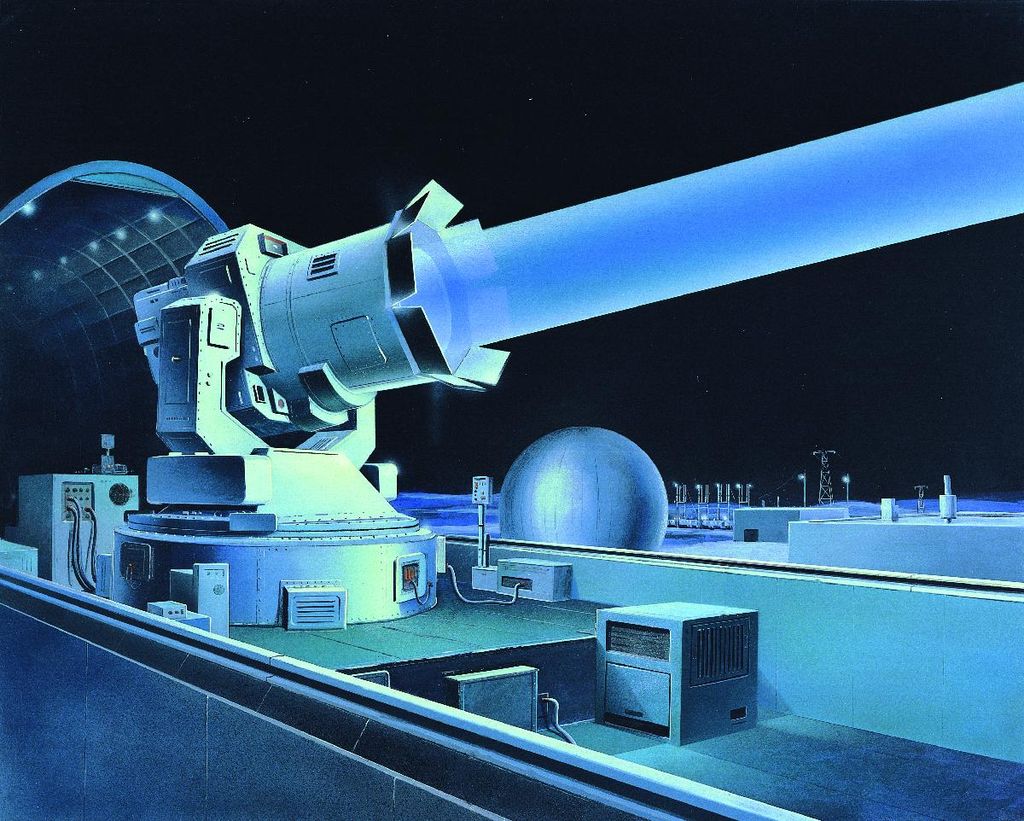

On March 27, 1984—more than a year after Reagan had announced SDI—Air Force Lieutenant General James Abrahamson was appointed as the first director of the Strategic Defense Initiative Organization (SDIO). The role of the organization, however, remained largely unclear. By 1985, SDIO was serving as an umbrella for the 22 think tanks and aerospace firms working on the program (O’Connell 76). The actual design of SDI was also unclear; scientists and experts considered an enormous number of possibilities. Options included both space-based and ground-based lasers, as well as a wide variety of missiles and tracking systems. Edward Teller, for example, was an early proponent of the satellite X-ray laser, although it was ultimately ineffective. Later on, the program focused on smaller, space-launched missiles known as “Brilliant Pebbles.”

SDI as Propaganda

The Strategic Defense Initiative was ultimately most effective not as an anti-ballistic missile defense system, but as a propaganda tool which could put military and economic pressure on the Soviet Union to fund their own anti-ballistic missile system. This possibility was particularly significant because, during the 1980s, the Soviet economy was teetering on the brink of disaster. “Why can’t we just lean on the Soviets until they go broke?” quipped Reagan (Lazzari 23).

Although Reagan was sincerely invested in SDI for the purposes of national security and never intended for it to be a bargaining chip, many of his advisors acknowledged its potential as a negotiating tool. Despite his concerns about the shortcomings of SDI as a legitimate system of defense, Shultz recalled saying at the time, “The Soviets will assume that we are on the verge of some special technical innovation. Maybe that is the greatest benefit” (251).

Shultz’s assessment proved to be correct. As Soviet Ambassador Dobrynin explained, the Soviet Union believed “that the great technological potential of the United States had scored again and treated Reagan’s statement as a real threat” (Gaddis 227). Soviet scientists were immediately tasked with investigating SDI. Physicist Roald Sagdeev, who was a part of this effort, recalled, “You know what the major argument was for investigating? What we were most afraid of? We were afraid that the industrialists in our military-industrial complex would say, ‘Great, we should do the same thing’” (Rhodes 202). Sagdeev later acknowledged, “If Americans oversold [SDI], we Russians overbought it.”

Soviet research into anti-ballistic missiles had begun in the 1970s, well before Reagan announced SDI, but it was quickly made a top priority in 1983. Above all else, Soviet leaders feared that SDI would pave the way for weaponizing space. Although the Soviet military budget remained a closely guarded secret, some American estimates concluded that it accounted for 15-17% of the Soviet Union’s annual GDP. The high point of Soviet anti-ballistic missile efforts came on May 15, 1987, when they launched an Energia rocket from the Baikonur Cosmodrome launch site in southern Kazakhstan. The rocket carried the Polyus spacecraft, which was equipped with a laser system, Skif, and a missile system, Kaskad. It was designed to shoot down SDI in space. In the end, Polyus failed to reach orbit and quickly broke apart.

When reformer Mikhail Gorbachev came to power in 1985, he began to drastically cut Soviet military spending, particularly the anti-ballistic missile program the USSR had started in response to SDI. In a speech to the Politburo in March 1986, Gorbachev exclaimed, “Maybe we should just stop being afraid of SDI! Of course we can’t simply disregard this dangerous program. But we should overcome our obsession with it. They’re banking on the USSR’s fear of SDI—in moral, economic, political, and military terms. They’re pursuing this program to wear us out” (Rhodes 224). Scaling back the military budget was one method Gorbachev used in his efforts to revive the Soviet economy; another was negotiating directly with the United States.

Arms Control Negotiations

The Strategic Defense Initiative became a key negotiating point in a series of meetings between Reagan and Gorbachev: the Geneva Summit (1985), the Reykjavik Summit (1986), the Washington Summit (1987), and the Moscow Summit (1988). These negotiations culminated in the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF), which went into effect in 1988, and laid the groundwork for the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START) in the 1990s. “The Strategic Defense Initiative in fact proved to be the ultimate bargaining chip,” recalled Shultz. “And we played it for all it was worth” (Shultz 264).

Although SDI was a frequent topic in negotiations with Gorbachev, Reagan was reluctant to surrender his project. At Geneva, for example, Reagan proposed that the two sides reduce their respective nuclear arsenals by 50% but was unwilling to surrender SDI. Once again, however, Reagan offered to share SDI technology with the Soviet Union, although not all of his advisors shared his enthusiasm for the proposal. “We had no idea where the idea had come from, none of us,” said Kenneth Adelman. “We thought it was wacko” (Rhodes 206). Gorbachev was skeptical that a sharing program could be arranged, arguing, “I do not take your idea of sharing SDI seriously. You don’t want to share even petroleum equipment, automatic machine tools or equipment for dairies, while sharing SDI would be a second American Revolution” (Hanhimaki and Westad 583).

Gorbachev was likewise flabbergasted by Reagan’s obsession with SDI. “Ronald Reagan’s advocacy of the Strategic Defense Initiative struck me as bizarre,” Gorbachev wrote in his memoirs. “Was it science fiction, a trick to make the Soviet Union more forthcoming, or merely a crude attempt to lull us in order to carry out the mad enterprise—the creation of a shield which would allow a first strike without fear of retaliation?” (Gorbachev 407). He argued that SDI was hypocritical—the West would be terrified if the Soviet Union developed an anti-ballistic missile system. In fact, Secretary of Defense Weinberger had said as much back in 1983: “I can’t imagine a more destabilizing factor for the world than if the Soviet should acquire a thoroughly reliable defense against these missiles before we did” (Rhodes 201).

At Reykjavik the following year, Reagan’s attachment to SDI again proved to be a significant obstacle to negotiations and the summit ended without a deal. As Gorbachev recalled, Reykjavik was “the site of a truly Shakespearean drama….Success was a mere step away, but SDI proved an insurmountable stumbling-block” (Gorbachev 418). By 1987, however, Gorbachev agreed that missile reductions and SDI could be negotiated separately. Along with reduced Cold War tensions, Gorbachev was aware that the U.S. Congress was cutting SDI’s budget and had been assured by physicist Andrei Sakharov that the missile defense technology was far from complete. The INF Treaty, which eliminated all short-range (310-620 miles) and intermediate-range (620-3420 miles) nuclear missiles, was signed at the Washington Summit later that year.

Legacy

Without Reagan to support it, SDI’s funding plummeted in the early 1990s. Although the program was never officially canceled, it was renamed under President Bill Clinton as the Ballistic Missile Defense Organization (BMDO).

Without Reagan to support it, SDI’s funding plummeted in the early 1990s. Although the program was never officially canceled, it was renamed under President Bill Clinton as the Ballistic Missile Defense Organization (BMDO).

In 2001, President George W. Bush announced his administration’s plan to withdraw from the ABM Treaty within six months. “A number of [rogue] states are acquiring increasingly longer-range ballistic missiles as instruments of blackmail and coercion against the United States and its friends and allies,” read an official statement. “The United States must defend its homeland, its forces and its friends and allies against these threats.” The anti-ballistic missile program was once again renamed, this time as the National Defense Agency (NDA). NDA, which still exists today, has studied the possibilities of space-based anti-ballistic missile technology, as SDI once did, although without any significant results to date.

In a speech to the Federal Assembly in March 2018, Russian President Vladimir Putin criticized the United States’ decision to withdraw from ABM and asserted the ability of Russian nuclear forces to penetrate any potential anti-ballistic missile system.