The Tularosa Basin Downwinders are individuals from central and southern New Mexico. They mostly reside or resided in Lincoln, Socorro, Otero, and Sierra counties, but can also include others outside of these parameters as well. They are known as “Downwinders” because of their location in relation to the Trinity nuclear test, which was conducted in the arid and sparsely populated Jornada del Muerto desert. The Downwinders state that they have experienced undue hardships in the years since Trinity because of the test’s radioactive fallout. The negative impacts include increased rates of cancer, other diseases that have caused financial and social stress, and death.

Location

The Trinity Site was selected due to its security and seclusion. Manhattan Project leaders chose the northern end of the United States Army Air Force Alamogordo Bombing and Gunnery Range. It fit the requirements that were needed for the test: the area was remote, the ground was flat, and the weather was fairly predictable with little to no wind. Most of the land around the site was either too dry for practical purposes, or was used periodically for grazing by cattle.

Cities nearby included Alamogordo, Carrizozo, San Antonio, Tularosa, Socorro, Mescalero, and Oscuro. Small ranches and trading outposts also dotted the valleys of the area. Only a few houses needed to be commandeered near the site, notably the McDonald Ranch House. Los Alamos laboratory director J. Robert Oppenheimer and Manhattan Project director Brigadier General Leslie Groves felt they had picked the perfect site for the world’s first nuclear test, a site that would be safe and secure.

The Test

On July 16, 1945, the United States became the first nation to successfully detonate a nuclear weapon. The Trinity test yielded twenty kilotons of force. The atomic age had begun. J. Robert Oppenheimer famously stated, in an interview twenty years later, “We knew the world would not be the same. A few people laughed, a few people cried, most people were silent. I remembered the line from the Hindu scripture, the Bhagavad-Gita; Vishnu is trying to persuade the Prince that he should do his duty and, to impress him, takes on his multi-armed form and says, ‘Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.’ I suppose we all thought that, one way or another.”

The test remained highly secretive, and almost immediately top Manhattan Project leaders set out on a campaign to downplay the loud explosion or bright light that people had witnessed so early in the morning, including individuals from cities as far away as Albuquerque and El Paso. Groves had previously drafted a press release to explain the incident, which he gave to William L. Laurence of The New York Times, who was on a special assignment to the Manhattan Project.

The release explained that a large cache of ammunition and pyrotechnics had exploded during the night, but that no one had been killed or injured. It also explained that due to weather conditions, there was a possibility that nearby citizens might be forced to evacuate. Such an evacuation never occurred — an evacuation would likely have panicked the public. Retrospectively, given the amount of radioactive fallout generated by the explosion, it is possible that an evacuation might have been the best course of action.

Fallout Levels and Early Warning Signs

Leading scientists had a relatively good idea about some of the hazards such a nuclear explosion would create. However, no one working on the project knew the exact scope or scale of the hazard. Some scientists, such as Emilio Segré, had expressed concerns that the bomb might ignite the atmosphere and destroy the entire world, while Groves and Laurence drafted several other public statements apologizing for the loss of life in nearby communities. Scientists knew that the bomb would create a large amount of radioactive fallout. The fallout could prove dangerous to local communities and the environment, as well as those working on the project. To minimize the risk of negative health effects for those working at the site after the test, lead-lined Sherman tanks were on hand for rock sample removal. Scientists and technicians who entered Ground Zero wore protective attire to block radioactive particles.

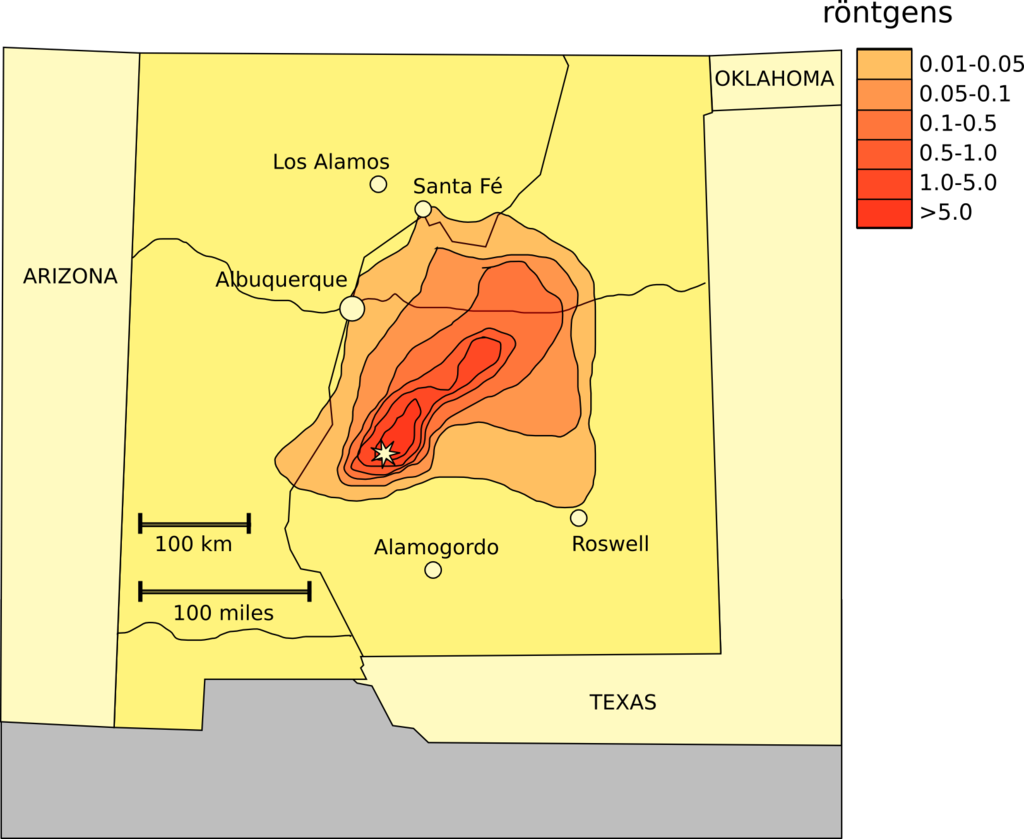

Most difficult to predict, however, was the fallout pattern for the blast. Wind and rain conditions were observed closely in the days before the blast. Scientists knew that radiation could shoot high into the atmosphere, possibly exposing people miles away in the process. How dangerous this radiation would be, and where it would go, however, was unknown.

Very little fallout actually fell on the test site itself; instead, the high, vertical mushroom cloud shot most of the radioactive materials upward and outward. Unlike some subsequent above-ground nuclear tests, the Trinity test exploded very close to the ground. Explosions this close to the ground caused far more radioactive material to be churned up and thrown into the air. This issue was remedied later on by having timed explosions while the bomb was still in the air.

The fallout pattern (pictured below) followed a northeast track, nearly 250 miles long and 200 miles wide. A central corridor of approximately fifty miles long and twenty miles wide received the brunt of the radiation, with observed values ranging from seven to more than ten roentgens per hour. Localized hotspots likely contained even higher values. The heaviest fallout settled on Chupadera Mesa, thirty miles from the detonation point. Here, cattle received severe beta burns — surface level burns from beta radiation particles that look similar to a sunburn — and were later purchased by the scientists at Los Alamos for further observation.

While Manhattan Project scientists were able to study the effects of radiation on the cattle they bought, accurate observations on humans were more difficult to measure. The Trinity test was top secret. Scientists were unwilling to approach ranchers or other individuals living in the area with dosimeters without giving the impression that something was awry. Consequently, Manhattan Project scientists gathered no data on civilian exposure, a fact that has plagued the Tularosa Downwinder community in its fight for compensation.

Health, Social, and Economic Impact

The full impact on the Tularosa Downwinder community is difficult, if not impossible, to gauge. Little was done immediately to assess the health of central and southern New Mexicans, and seventy-plus years have passed since Trinity. However, individuals in the area were almost certainly exposed to dangerously high levels of radiation.

A main issue in the Tularosa Basin was the absence of running water in many of the rural New Mexican communities. Fresh sources of water from distant reserves were not used; rather, locals relied on cisterns and holding ponds nearby for their fresh water. Fallout also landed on vegetables and animals, food sources that would be consumed by the Downwinders. Eating food sources that have higher radiation levels can lead to various cancers, birth defects, and stillbirths, all issues that Tularosa Downwinders say have plagued their communities. Personal testimony and data seem to affirm these claims. Radioactive exposure has also been linked to epigenetic changes. When exposed to high doses of radiation, genes can mutate in the person exposed, which is then passed on to successive generations. Often these mutations cause diseases that did not previously appear in the family, such as heart disease or leukemia, to become hereditarily passed down.

Matters are complicated further by economic and social factors. Access to proper medical care services is difficult, oftentimes requiring Downwinders to drive hours to the nearest hospital. A survey conducted in 2017 shows that Lincoln, Socorro, Otero, and Sierra counties face economic challenges, as all four have average household incomes below the state and national average. Many Tularosa Downwinders have been forced to dip into already tight savings accounts to pay for treatments. Some individuals have lost their jobs due to illnesses, while others have pre-existing ailments which limit their job opportunities.

From personal testimony, perhaps the biggest impact on the Tularosa community is generational trauma and mental health. Downwinders describe how different their lives are now that they believe hunting, fishing and farming may have negative impacts on their physical health. Many feel these lifestyle changes have altered their identities as individuals, families, and a community. Others feel unacknowledged for the suffering they, and loved ones, have experienced. Financial compensation is important for the Tularosa Downwinders economically, but perhaps more importantly it validates their hardship.

Legal Action

Litigation continues for the Tularosa Downwinder community. The Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA), passed in 1990 and amended in 2000 and 2002, does not include Tularosa Downwinders. RECA provides $50,000 to $100,000 in financial compensation for health related expenditures associated with radiation exposure. It covers the Nevada Site Downwinders, certain groups of uranium miners, and workers who participated in atmospheric tests.

The Tularosa Downwinders continue to lobby to become a part of RECA. Recognition under RECA also may ease the qualification for some with pre-existing conditions to get Medicare and Medicaid. After years of litigation, and more than ten years of attempting to get a vote in Congress, a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing on the Downwinders was held on June 27, 2018. Spearheaded by a coalition of Tularosa Downwinders and Navajo leaders, such as Tina Cordova and Jonathan Nez, advocates now await a Senate vote to expand RECA. New Mexico Senator Tom Udall, Idaho Senator Mike Crapo, and New Mexico Representative Ben Ray Luján are among the legislative backers of the Downwinders as they aim for their long-awaited inclusion under RECA.

For more on the Trinity Site Downwinders, see the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium’s 2017 Health Impact Assessment (HIA): “Unknowing, Unwilling, and Uncompensated: The Effects of the Trinity Test on New Mexicans and the Potential Benefits of Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA) Amendments.” Journalist Kelsey D. Atherton also wrote about the Downwinders in a 2017 article in Popular Science. You can visit the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium’s website at www.trinitydownwinders.com.