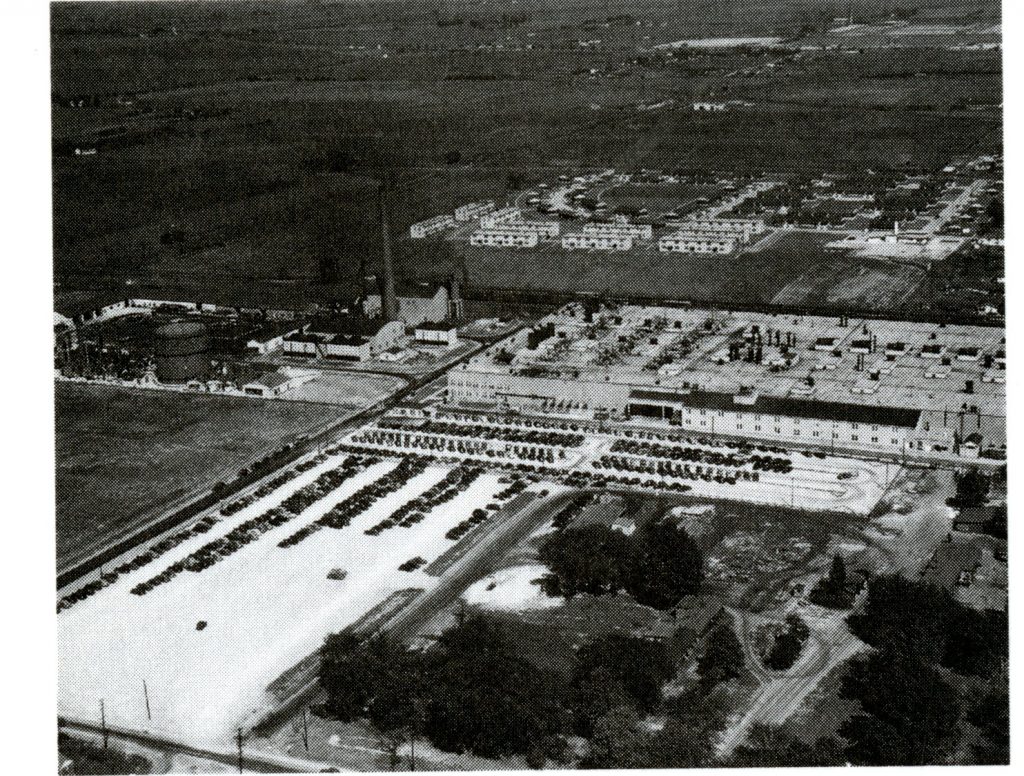

Decatur, IL

The Houdaille-Hershey Plant was a secret Manhattan Project site located in Decatur, Illinois. It was responsible for plating the interior of pipes with a barrier material that could be used for the gaseous diffusion process for enriching uranium at the K-25 Plant at Oak Ridge, Tennessee. Prior to World War II, the plant was used to produce automobiles.

The continuing failure to develop a suitable barrier material for the gaseous diffusion process by 1943 led to a renewed sense of urgency to develop an adequate material that could withstand the high pressure of the heavy, corrosive gas used in the process. By January 1943, interior-decorator Edward Norris and chemist Edward Adler had perfected an electro-deposited nickel mesh barrier that seemed promising. With the gaseous diffusion process then dead in the water, General Leslie Groves authorized full-scale production of the “Norris-Adler” barrier with the hope that this new material would revive the failing process. On April 1, 1943, the Houdaille-Hershey Corporation, best known as a manufacturer of shock absorbers for automobiles, began constructing a factory to build the barrier in Decatur.

However, by the fall of 1943, the Kellex Corporation, the operating contractor for the K-25 Plant, had produced another barrier material that combined the Norris-Adler barrier and another compressed nickel-powder method. Project leaders then had to decide the fate of the Decatur plant, which was still under construction. Kellex advocated stripping and converting the Houdaille-Hershey Plant, which might delay the completion of K-25 but would prevent the adoption of a barrier method that might not work. At Columbia University, scientist Harold Urey warned that scrapping the Norris-Adler barrier would prevent the Project from producing enough U-235 by gaseous diffusion to make a bomb.

In January 1944, General Leslie Groves resolved the dispute by deciding to switch over to the new, superior barrier. The Houdaille-Hershey plant was stripped and reequipped to produce the new material. Workers at the plant were tasked with nickel-plating all the pipe interiors, a difficult new process accomplished by filling the pipes themselves with a plating solution and rotating them as the plating current did its work.

[The text for this page was adapted from Richard Rhodes, The Making of the Atomic Bomb (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1986), 494-6].