France

An Introduction to French Nuclear History

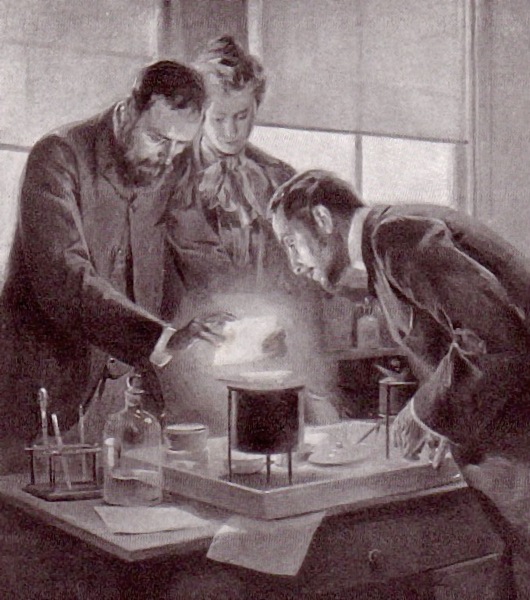

France was the premier place for research into radioactivity decades before the development of the bomb. The process started under Henri Becquerel, who first discovered radioactivity in 1896. Marie and Pierre Curie expanded upon his findings, discovering that radioactivity is based within the atom itself, rather than molecular interaction. For these and other discoveries related to radioactive elements, Becquerel and the Curies would jointly receive a Nobel Prize for their work in 1903, and Marie earned another in 1911, after Pierre died.

The Curies’ daughter Irène and her husband Frédéric continued their nuclear legacy, discovering how to produce radioactive isotopes in an artificial manner, as opposed to expensively separating them from ore. This allowed for much cheaper radioactive material, and won the couple a Nobel Prize in 1935. Frédéric and his team also led early efforts into nuclear research, producing a fission reaction in January 1939.

Once World War Two commenced later that year, the French government began to seek out nuclear materials, including uranium ore procured from the Belgians and the entire world’s supply of heavy water from the Norsk-Hydro plant in Norway. These efforts were thrown into disarray when the Germans invaded in May 1940, necessitating the heavy water being snuck out of Paris in the dead of night to Britain. Frédéric and Irène decided to remain in France, continuing their research. Frédéric also became a leader in the French Resistance during the occupation years.

Following the conclusion of the war, Frédéric was appointed head of the Commissariat of Atomic Energy (CEA – Commissariat à l’Energie Atomique). Following the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, he argued for the peaceful uses of atomic energy, and made them a significant focus of his early tenure at CEA. He produced France’s first atomic pile in 1948, but his plans were soon cut short due to his opposition to nuclear militarization. His downfall started with his propagation of the Stockholm Appeal, a petition for the ban of all nuclear weapons. His reputation was also damaged by his alliance with the French Communist Party, who were of like mind on the issue of nuclear proliferation. As a result of France’s growing anticommunism with the raising of the Iron Curtain, the CEA dismissed Joliot-Curie in 1950. Throughout the 1950s, Frédéric’s dreams of fission for energy on a national scale began to become reality, with several reactors being established by 1959.

Possessing nuclear weaponry soon proved to be a tempting concept for France. International setbacks such as the Suez Crisis of 1956 and decolonization led to a perception in French society that France needed to assert its power. The answer to this sentiment came in 1959 with the reelection of Charles de Gaulle, a strong proponent of France having the bomb. The military set up a nuclear test site in the Algerian Sahara, with the first test being a 70 kiloton yield bomb in February 1960. France tested dozens of nuclear weapons above and below ground until 1966, several years after Algerian independence. Fallout was a serious concern for the Algerians and several neighboring countries, but shifting sands have made it impossible to properly gauge the effect of this fallout. These tests were meant to indicate strength and sovereignty to the international community, in line with concurrent actions such as France disintegrating its ties to the NATO command structure in 1966.

Following the closure of the Algerian test site, a new one was selected at the Tuamotu atolls of Mururoa and Fangataufa, near Tahiti. Despite assurances from the French government, fallout spread from the atolls was greater than expected, with increased instances of various kinds of cancer on Tahiti and other populated islands in French Polynesia. Almost 200 tests were conducted on these islands, with at least a dozen conducted during a period in 1995/96, halting only after widespread outside pressure and boycotts across the world. French nuclear tests were only officially ended in 1998, with French ratification of the Comprehensive Nuclear Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT).

To this day, France has the third largest nuclear arsenal, capped at about 300 warheads by the government and deployable by aircraft or submarine. France has also officially recognized the ill effects of radiation exposure following a 2009 parliamentary bill, providing compensation for some of those who worked on the nuclear tests. They also acknowledged that some soldiers were intentionally exposed to radiation to study its effects, but under the notion that the 1960s were a different era, and that those who ran the tests had very rudimentary knowledge compared to today.

On the energy side, the 57 reactors run by Électricité de France (EDF) currently account for 75% of France’s energy needs, and a significant amount of energy exports, making France one of the most nuclear-integrated nations in the world. However, there seems to be a trend of declining support amongst the French public for nuclear energy, leading to some uncertainty about the future of nuclear power generation in France.