Los Alamos, NM

Los Alamos, New Mexico, was the site of Project Y, or the top-secret atomic weapons laboratory directed by J. Robert Oppenheimer. The site was so secret that one mailbox, PO Box 1663, served as the mailing address for the entire town. The mountains allowed the scientists ample opportunity to relax, by skiing, swimming, and hiking. But they spent most of their time in laboratories, overcoming challenge after challenge to develop the Little Boy (gun-type) and Fat Man (implosion) atomic bombs. Because the name “Los Alamos” was considered classified information, the installation was variously identified as Site Y, Project Y, the Zia Project, or Santa Fe Area L. However, most residents of Los Alamos and Santa Fe simply referred to it as “The Hill.”

Los Alamos Site Selection

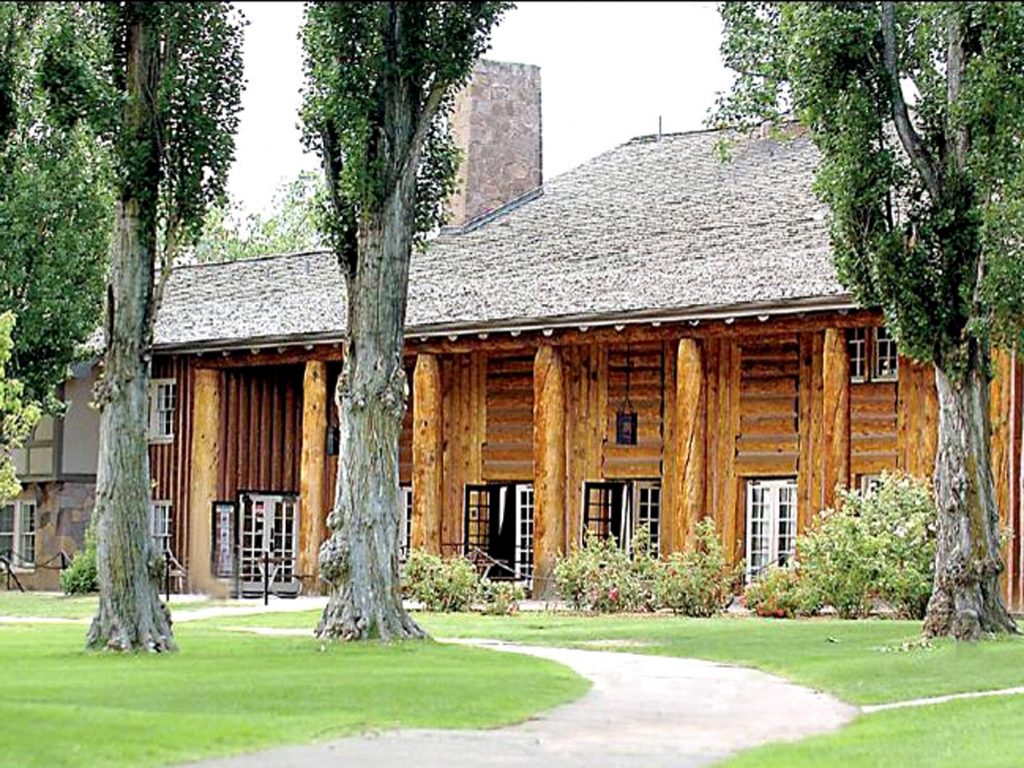

New Mexico boasts of great beauty and history, and for a variety of reasons proved the perfect place for a top-secret weapons laboratory. The Los Alamos Site Selection was a relatively quick process. In November 1942, the Manhattan District authorized the Albuquerque Engineer District to conduct a site investigation in the vicinity of the Los Alamos Ranch School in Otowi, New Mexico. In 1918, entrepreneur Ashley Pond began an “outdoor school” at Los Alamos to provide boys a chance to gain health, strength and self-confidence. The Los Alamos Ranch School combined a rigorous outdoor experience with a college preparatory education. The Los Alamos Ranch School comprised 54 buildings: 27 houses, dormitories, and living quarters totaling 46,626 sq. ft., and 27 miscellaneous buildings: a public school, an arts & crafts building, a carpentry shop, a small sawmill, barns, garages, sheds, and an ice house totaling 29,560 sq. ft. There were also 4 houses, with approximately 20 rooms, and a small barn at the Anchor Ranch site.

Reports comparable to those submitted on the proposed Jemez Springs were prepared. The fact that the existing Los Alamos Ranch School buildings could be used for immediate housing was a primary factor in the recommendation of the site. Further, Otowi was more accessible, had a better water supply and lower valuation, and lay in a more sparsely populated area than Jemez Springs. All of these advantages plus the following favorable points could not be readily ignored.

Reports comparable to those submitted on the proposed Jemez Springs were prepared. The fact that the existing Los Alamos Ranch School buildings could be used for immediate housing was a primary factor in the recommendation of the site. Further, Otowi was more accessible, had a better water supply and lower valuation, and lay in a more sparsely populated area than Jemez Springs. All of these advantages plus the following favorable points could not be readily ignored.

Most of the area (some 47,000 acres of the estimated 54,000 required) could be obtained easily because it was already owned by the Federal government. The private portion of the land was used mainly for grazing so the purchase price would be relatively small. There was enough area available to ensure safe spacing of the various Project units. The nearest town was 16 miles away, which tended to isolate the site. The area was located on a mesa, making entrance to the site easy to control. The main site area was relatively free from timber, and would necessitate little clearing.

Representatives from the Manhattan District, the Albuquerque District, and the Southwestern Division Real Estate Branch met in November 1942 at the Los Alamos Ranch School to consider that location in detail. The choice of the site was also discussed with J. Robert Oppenheimer, Project Director, and members of his staff, for further confirmation of its desirability. After careful consideration of all the cumulative reports and recommendations, General Leslie Groves determined that Project Y would be centered at the site of the Los Alamos Ranch School in Otowi, New Mexico.

By 1942, J. Robert Oppenheimer was one of the world’s leading theoretical physicists at the University of California at Berkeley and had been appointed scientific director of the top-secret weapons project. The Pajarito Plateau soon became the center of an effort that would harness the energy of the atom. For Oppenheimer, it was a marriage of his two great loves, physics and New Mexico.

Design & Engineering

Design and engineering, through March 1944, were supervised by the Albuquerque Engineer District of the Southwestern Engineer Division. Then the Manhattan Engineer District (Manhattan Island, New York City) assumed supervision. Because technical design depended largely upon the development of research and experimental processes, actual needs and requirements continually demanded major or minor alterations. The firm of W. C. Kruger was selected as architect-engineer for initial design and engineering and continued its work under Manhattan District supervision.

The Albuquerque District negotiated a contract for design of the originally authorized buildings and utilities with the Kruger Company because they maintained a competent architectural and engineering staff. Further, their office was in Santa Fe, in a good position to collaborate with the Operating Contractor (University of California) about special technical issues not ordinarily covered in standard Army construction.

The Secret City

Los Alamos was so secret that it was not on any map. No one who went to live and work at Los Alamos was allowed to tell friends or family members where they were going.

Los Alamos was so secret that it was not on any map. No one who went to live and work at Los Alamos was allowed to tell friends or family members where they were going.

A single post office box, P.O. Box 1663, served all Los Alamos’s residents. Babies born during the Manhattan Project had “P.O. Box 1663” listed as their birthplace on their birth certificates. Sears & Roebuck delivery men became suspicious when orders for a dozen baby bassinets came from the same address. By the end of the war, five thousand people were assigned P.O. Box 1663.

Physicists, chemists, metallurgists, explosive experts and military personnel converged on the isolated plateau. At times, six Nobel Prize winners gathered with the other scientists and engineers in the weekly colloquia organized by Oppenheimer. Meanwhile, the Army was charged with supporting the work, building buildings, keeping the commissary supplied, and guarding the top-secret work. Members of the Special Engineer Detachment – Los Alamos worked on the bomb.

Hurriedly built, huge laboratory buildings sprawled along the south side of Ashley Pond. Rows of four-family apartments strung to the west toward the mountains. A few board sidewalks raised residents up out of the mud that was prevalent in winter when snow melted and in summers during the afternoon monsoons.

V-Site

Located in a bucolic setting surrounded by tall pines, these humble wooden and asbestos-shingled buildings were where the world’s first atomic device was assembled. Here scientists, engineers, and explosives experts worked around the clock on the “Gadget,” the first plutonium-based atomic explosive.

The original V-Site buildings were fortified by mounds of earth to protect them against accidental explosions. High explosives were melted, mixed and poured into molds at neighboring S-Site to produce the lenses that surrounded a core of plutonium.

The 32 lenses were fitted together like a soccer ball. Each lens had to be detonated at precisely the same time. A shock wave compressed the core to bring the plutonium to a critical mass. The energy released was equivalent to 21 kilotons of TNT. This painstaking assembly was accomplished at the V-Site behind a “no peek” fence. Once completed, the Gadget was tested on July 16, 1945, at Trinity near Alamogordo, NM.

The V-Site was awarded a Save America’s Treasures grant by the National Park Service in 1999 after being slated for demolition. However, the Cerro Grande Fire in May 2000 destroyed all but two of the original buildings.

The V-Site was restored in 2006 after the Atomic Heritage Foundation raised the matching funds for the grant. In 2008, the National Trust for Historic Preservation honored the V-Site Restoration Project with a National Trust/Advisory Council on Historic Preservation Award for Federal Partnerships in Historic Preservation.

Gun Site

The Gun Site (TA-8-1) was where Manhattan Project scientists and engineers developed and tested the gun-type weapon design in Los Alamos, NM. The design for the Little Boy bomb dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, was developed here.

The Gun Site (TA-8-1) was where Manhattan Project scientists and engineers developed and tested the gun-type weapon design in Los Alamos, NM. The design for the Little Boy bomb dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, was developed here.

The gun design was straightforward. Basically, a “bullet” of nuclear material was fired at very high speed into a second nuclear mass, creating a critical mass. This released enormous energy with an immense explosion. Scientists were confident the design would work and the gun-type bomb was not tested before it was used against Japan.

The Gun Site had a large proving ground above the bunker-like buildings. Two Naval cannons were hidden from view by wooden housing on rails. The housing could be removed when the cannons were fired. The team observed the firings from the bunkers through a periscope mounted in a 45-foot tower. After a test firing, they retrieved the projectiles and analyzed the test results in a work area equipped with a camera room, darkroom and X-ray equipment.

Currently, work is underway to restore the facilities as they were during the Manhattan Project.

Santa Fe

Santa Fe was the first stop for many scientists, engineers, Women’s Army Corps, military police and all others assigned to work on the top-secret project at Los Alamos. Ten miles from Santa Fe, Lamy is the nearest stop on the former Atchinson, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway. Young men and women assigned to work at Los Alamos arrived not knowing where they were or where they were going.

After arriving in Lamy, the scientists, SEDers, and families were directed to 109 E. Palace Avenue in Santa Fe. The building, constructed as a Spanish hacienda in the 1600s, is located just off the plaza in downtown Santa Fe. During World War II, it was the administrative hub of the Manhattan Project.

Dorothy Scarritt McKibbin was the first reassuring face the fatigued newcomers saw. At 109 East Palace, McKibbin informed them that their journey continued another 35 miles along the winding road up to the Pajarito Plateau. In the early months, she dispatched an average of 65 people each day to “the Hill,” as Los Alamos was called. The steady stream of arrivals meant the office was often “bedlam,” as McKibbin described it. She issued passes and IDs and directed newcomers to their homes, received shipments of household items to be distributed to the Hill’s residents, and tended to personal matters as needed. McKibbin was the perfect person for her job and quickly became indispensable as the “Gatekeeper” at 109 E. Palace Avenue and a close friend and confidante of Oppenheimer. She had a warm smile, an engaging personality and was reassuringly calm and efficient. In recognition of her contribution, McKibbin was awarded the title of “First Lady” of Los Alamos and declared a Living Treasure of Santa Fe.

Located at 100 East San Francisco Street, La Fonda (Spanish for “inn”) was a favorite watering hole for the scientists and their wives who ventured down from the Hill for a taste of civilization during the Manhattan Project. Fearing that they might loosen up too much and reveal the project’s top-secret goal, covert government agents monitored Los Alamos residents as they unwound here. Santa Fe residents were trying to figure out what the secret project was at Los Alamos. Worried that they might guess correctly, Oppenheimer asked physicists Bob Serber and John Manley to go to Santa Fe with their wives to spread the rumor that Los Alamos was making electric rockets.

Another historic site in Santa Fe, the Castillo Street Bridge at Paseo De Peralta was where German physcist and Soviet spy Klaus Fuchs agreed to meet his Soviet Agent, Harry Gold, on June 2, 1945. Fuchs met with agent Gold many times over the summer of 1945 and gave the Soviet Union valuable data. Together with two other sources, Fuchs enabled the Soviets to expedite their atomic bomb development by at least two years.

For more than twenty years, Edith Warner and her companion Atilano Montoya (nicknamed “Tilano”), an elder of the nearby San Ildefonso Pueblo, lived in a small adobe house next to the Otowi Suspension Bridge. “Otowi” in Tewa means “the gap where water sinks.” The house became a cultural crossroads between local ways of life and the Manhattan Project.

Dinner at the house at Otowi Bridge was booked weeks in advance. The house was decorated with beautiful Native American artifacts, pottery and paintings. Up to ten guests dined together at a single long, carved table. The natural light from the fireplace filled the room with a cozy glow. The food was simple and delicious: a stew with fresh herbs; posole, a Native American dish made with parched corn; poached fruit; and Warner’s magical chocolate cake. From 1928 to 1941, Warner was in charge of meeting the “Chili Line” railroad on its way to and from Santa Fe. With the outbreak of World War II, the train service ended. Warner agreed to Oppenheimer’s request to serve meals exclusively to Los Alamos scientists and their families in 1943.

Further Reading

For more information on the Manhattan Project’s sites in New Mexico and the scientists who worked there, please consider purchasing our Guide to the Manhattan Project in New Mexico, which can be found on at Amazon. Additionally, WorldCat checks local libraries for copies in your area.

[The text for this page was taken and adapted from Edith C. Truslow, Manhattan District History: Nonscientific Aspects of Los Alamos Project Y, 1942 through 1946 (United States Atomic Energy Commission, 1973), 2-3.]