Clarence Johnson (1912-2012) was a Canadian-born chemical engineer.

He was born in Alberta, Canada on November 24, 1912 to Swedish migrant parents. He was raised in a remote cabin, and began working on his family’s small farm to help his parents and siblings subsist. The family had so few resources that, in order to fund his aspirations of higher education, Johnson took up fur trapping for a time. He was accepted to study at the University of Alberta, where he majored in chemical engineering. He continued on there to complete his M.S. in engineering.

Johnson’s performance at Alberta caught the eye of faculty at MIT, who offered him admittance, a scholarship, and even a spot on the faculty after he completed his Ph.D. After the United States entered World War II, demand for engineers in the war effort rose substantially. Johnson decided to leave teaching and joined the M. W. Kellogg Company which at the time was working in partnership with the government on uranium enrichment for the Manhattan Project.

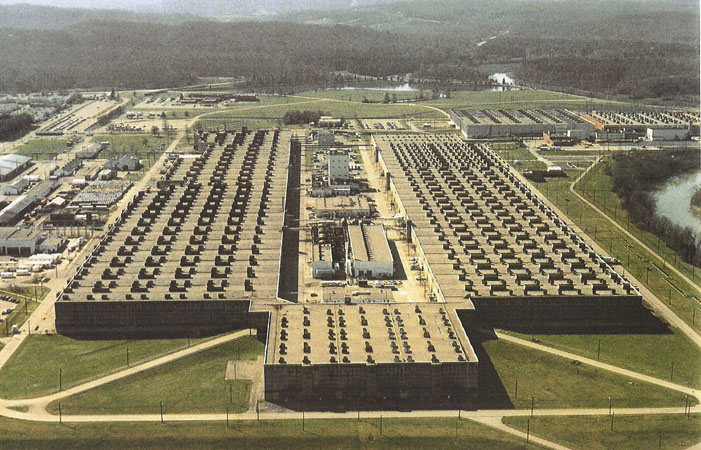

Johnson was placed in charge of experimental research in Kellogg’s “X” Division—a wholly owned subsidiary of Kellogg known as “Kellex.” This company was tasked with two major, overlapping goals: establish a successful and massively reproducible process for gaseous diffusion and implement this process at a site called “K-25” in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. Johnson was responsible for designing the barrier material that could separate U-235 atoms (an isotope of uranium able to undergo fission) from U-238 (an isotope that could not).

On June 19, 1943, Johnson and his assistant Tony Suleski were working late into the night in their Jersey City laboratory when they finally tested a barrier prototype that could effectively separate U-235. After over a year of trial and error, Johnson and his team had finally come up with a successful design. For months, technicians at the K-25 plant at Oak Ridge had been working with a problematic and difficult diffusion design known as the “lace curtain.” General Leslie Groves ordered Clarence Johnson’s design to replace the lace curtain. Implementation of the Johnson model substantially reduced the engineering obstacles at Oak Ridge and quickened the pace by which the bomb could be completed.

After the war, Johnson shifted his focus towards fossil fuel facilities. He designed oil refineries and engineered a process to convert coal into gasoline. Throughout his life, Johnson held or contributed to 13 U.S. Patents.

Dr. Clarence Johnson died on March 18, 2012 at the age of 99.